America needs a lot more cities that offer both great work opportunities and reasonably priced homes. This means improving affordability in large, high-opportunity places so more people can access thriving job centers, but it also requires expanding economic opportunity in relatively affordable places.

Over the past decade, economic fortunes have taken a surprising turn for the better in a group of localities we call “liminal cities” – small, semiurban, and very affordable cities physically located between large metropolitan areas and rural regions. Places like Jefferson, Georgia, near Atlanta; Granbury, Texas, in the Dallas-Fort Worth metro; and Baraboo, Wisconsin, outside Madison.

The most successful liminal cities share common characteristics. They’ve developed reputations for small-town charm, vibrant town centers, a strong sense of community, and good schools. Residents typically have good access not only to opportunities in the nearest large metro area but also to jobs in nonglamorous but well-paying industries closer to home, like agribusiness in Jefferson and auto parts manufacturing in Lewisburg, Tennessee and Greensburg, Indiana. Each of these cities experienced very slow (or negative) population growth for decades until 2000 or even 2010 but explosive growth in more recent years.

Today’s successful liminal cities show one way to build affordable, opportunity-rich places in 21st century America. A new George W. Bush Institute-SMU Economic Growth Initiative report suggests the following takeaways: Focus on quality of life, strong schools, a cohesive sense of community, ease of doing business, and well-functioning physical and digital connections to nearby large metropolitan areas. Liminal cities following this straightforward plan are mostly booming today.

We’ve identified 288 small micropolitan areas, as the federal government defines them, that are collectively home to 15 million people and that we characterize as liminal cities because they meet three criteria:

- They have populations between 10,000 and 100,000.

- They are within 100 miles of one of America’s 60 largest metros.

- At least 5% of the working population commutes at least some of the time to one of the 60 largest metros, demonstrating that it’s manageable to do so.

Until recently, liminal cities typically lost population over time to larger metro areas nearby. One indicator: Our liminal cities experienced considerably less home price appreciation from 1990 to 2010 than either the 60 largest metros or another group of further-out, non-liminal micro areas.

But economic opportunities have improved dramatically for people living in America’s liminal cities, the Bush Institute-SMU Economic Growth Initiative report shows. Liminal cities are benefiting from three tectonic shifts in the economy:

- Hybrid work allows people to live relatively far from workplaces and commute less than five days a week. The share of workers who work remotely at least some of the time has increased much more in liminal cities than in their non-liminal counterparts.

- Broadband connections are rapidly improving. Download speeds in our liminal cities are about 70% as fast as in large metro areas – much better than a decade ago.

- New exurban job centers in large metros are often much more reachable from liminal cities than traditional downtowns, so commutes can be shorter than in the past.

Thanks to improving work opportunities, incomes have grown faster in our liminal cities than in the 60 largest metros. Median household incomes rose about 30% in our liminal cities from 2010 to 2021, compared with about 28% growth in the nation’s 60 largest metros, measured as nominal changes in the population-weighted average for each group of cities. The liminal cities’ edge in income growth is especially pronounced for people who work remotely at least part of the time.

While incomes are still lower than in the largest metros, home prices are 20% less expensive in our liminal cities, on average. After adjusting for lower living costs, gaps in living standards relative to large metros are considerably smaller. Consequently, liminal cities as a group have seen net in-migration from elsewhere in the United States since 2017, while both the largest metros and non-liminal micro areas have each collectively experienced net out-migration.

Unheralded success stories

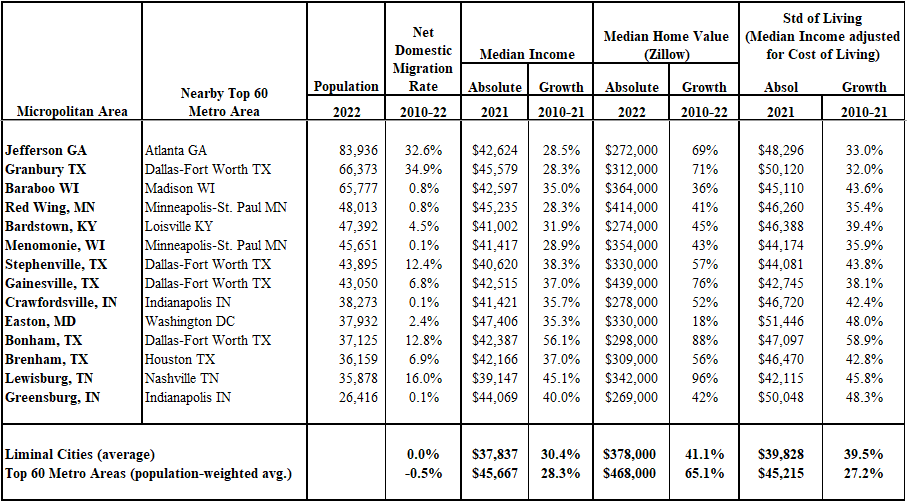

Fourteen of our liminal cities score better than the average of America’s 60 largest metros for median income growth, growth in housing-cost-adjusted living standards, and net domestic in-migration, and roughly in line or better for their absolute level of living standards after adjusting for housing costs. (See table below.)

Nine of these cities have achieved income growth rates fully 20% higher than the 60 largest metros as a whole. All but one has performed more than 20% ahead of the largest metros for cost-adjusted living standards. And five of them – Jefferson, Georgia; Granbury, Texas; Stephenville, Texas; Bonham, Texas; and Lewisburg, Tennessee – have seen net in-migration rates larger than all but the fastest-growing large metros.

The revival of many liminal cities shows that it’s possible to combine better-than-average economic opportunity with affordability in small, previously struggling places, at least in some locations. It’s a matter of getting the basics right, creating communities where people want to live, and welcoming growth.

Successful Liminal Cities