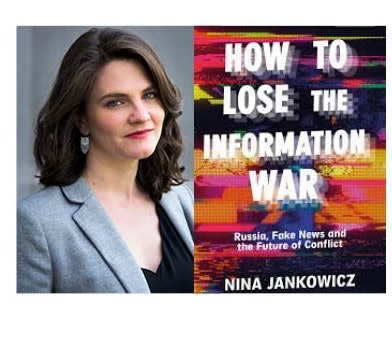

Nina Jankowicz writes in How to Lose the Information War that disinformation campaigns prey upon societal fissures.

If there is just one point to glean from Nina Jankowicz’s How to Lose the Information War, it is this: The threats that disinformation campaigns present democracies do not occur in a vacuum. The intentionally false or distorted information flowing out of places like Russia and China, and aimed at nations from North America to Africa to Europe, is part of a larger effort to prey upon divisions, especially within democratic societies.

For that reason, whatever strategy a nation employs to counter bots, trolls, and outright lies must go together with a robust civic renewal effort. Otherwise, the Woodrow Wilson Center scholar writes, democracies will play a never-ending game of whack-a-mole.

The Czech experience

Jankowicz, who previously worked for the National Democratic Institute’s Russia program, offers several examples of how Russian disinformation campaigns have sought to exploit societal fissures. As one example, she reports how Russians in particular seized upon the sharp distrust in the Czech Republic of Muslims as migration expanded across Europe in the last decade.

The disinformation onslaught had an effect. Jankowicz describes how “… a search on the EU’s database of disinformation turns up hundreds of fake or misleading stories from Czech outlets over its three years of data collection. Some of the most outlandish headlines claim that ‘due to migration, the number of rapes in Sweden has increased by 1000% in two years,’ ‘hundreds of thousands of Arabs are waiting for Czech citizenship and a social benefit of 21,000 CZK (about $1000) per month’ and that ‘pork is disappearing from the German restaurants and school cafeterias to please Muslim refugees.’”

The irony is that the Czech Republic has only about 10,000 Muslims out of a population of 10.7 million people, according to the U.S. State Department. Still, Jankowicz writes, the false posts played upon Czech fears and discriminatory attitudes. (The 2019 Pew Research Global Attitudes Survey revealed that 64 percent of Czech respondents expressed unfavorable opinions of Muslims.)

Websites based in Russia and the Czech Republic used those anxieties to amplify concerns about immigration, terrorism, and Islam. Jankowicz details how a Czech national security audit made clear that Russian disinformation efforts “weaponized” Islamophobia to Russia’s advantage. The audit, which devoted half of its chapters to this problem within Czech society, led to the creation of the Center for Terrorism and Hybrid Threats.

If there is just one point to glean from Nina Jankowicz’s How to Lose the Information War, it is this: The threats that disinformation campaigns present democracies do not occur in a vacuum.

Jankowicz describes that Center’s work at length, but the short take is that she considers that work a missed opportunity. It focused too much on Russia rather than on the internal fear of Muslims and created consternation among some that the Center would lead to censorship. She contends that greater openness and dialogue about those tensions “are the key to repairing the root divisions that cause disinformation, whether in Prague or far beyond.”

In other words, address why domestic tensions exist, and you can go far in minimizing the influence of foreign and domestic disinformation efforts.

Ukraine’s example

Jankowicz laid the groundwork for this book as a Fulbright Public Policy Fellow in Ukraine. She started there in 2016, which was two years after pro-government forces fired upon Ukrainians who were protesting for their nation to turn away from Vladimir Putin’s Russia and toward the democratic European Union (EU).

She reports how pro-European Ukrainians failed to sway a Dutch referendum that opposed a proposed agreement to allow Ukraine to strengthen economic ties with the EU. Ukrainians lost to a disinformation campaign that was “amplified on the fringes of Dutch politics and the pages of Russian propaganda — the predecessor to Russian involvement in Brexit and the [2016] U.S. presidential election.” As she explains, “Russian-backed media in the Netherlands, including the Dutch versions of Kremlin-funded propaganda networks RT and Sputnik, began pushing out anti-Ukraine narratives to provide fodder for the campaign.”

Ukraine certainly has been at the epicenter of Russian disinformation efforts. GOP Sen. Rob Portman of Ohio detailed in a Bush Center Democracy Talks interview this fall how when Russia invaded Crimea, the Russians used “ … a combination of kinetic military and disinformation. And sadly it was effective. They continued to use that on the eastern border of Ukraine and the conflict there and in Ukraine itself and through the Ukrainian community here in Ohio.”

Jankowicz describes this kind of hybrid warfare throughout her book. The strategy includes aggressor nations using traditional weaponry in some places. But it also may employ something like the Internet Research Agency, which is the Russian troll farm that used Ukraine to pioneer its strategy of exploiting societal fissures.

the lesson we should take from her research is that, in the United States at least, we should double-down with a dual approach. Let’s renew our bonds of trust while also investing in efforts to shine the light on disinformation campaigns.

Plugging up our own fissures

Jankowicz combines an easy storytelling style with in-depth reporting in this book. My favorite description is of one figure she met in Prague: “Janda cast himself in his role as activist in the costume of a think-tanker.” And she also includes chapters on disinformation efforts exacerbating tensions in places like Georgia, Poland, Estonia, and, yes, the United States.

As we pivot and think about the world beyond 2020, the lesson we should take from her research is that, in the United States at least, we should double-down with a dual approach. Let’s renew our bonds of trust while also investing in efforts to shine the light on disinformation campaigns.

From my perspective, the best place to start the renewal effort is at the community level. We all know we have divisions. But how do we live respectfully with our differences and not let them destabilize our democracy?

Fortunately, examples abound of Americans attempting to work out their differences. The Aspen Institute’s Weave program showcases how people across the country are attempting to “weave together” inclusive, strong communities. James and Deborah Fallows report regularly in The Atlantic how cities and towns across the U.S. are working through the difficulties of renewing their communities. And here in Dallas, as is true elsewhere, conversations are taking place about how to understand and overcome our racial divides. (My church is now into its sixth month of hour-long Zoom discussions about racial inequities.)

Civic renewal doesn’t happen easily and certainly doesn’t mean we will lack sharp differences. But the more we can talk through them in our neighborhoods, town halls, and civic associations, the more we can keep disinformation efforts from using those disagreements as a wedge issue.

As far as tools to stem disinformation flows, building up the State Department’s Global Engagement Center is one way to respond. Jankowicz doesn’t seem to think much about its efforts so far. But Sen. Portman, who authored the bipartisan legislation that led to the Center’s creation, noted in his Democracy Talks interview how it is now being built up.

Another important strategy is expanding media literacy courses, including in our K-12 schools. The good news is that courses are emerging that can help consumers of news to discern whether the information they are reading or viewing is true or not.

We will need all these tools and more to counter this modern security threat. As Jankowicz concludes, “Russian deceptions exploit fissures in targeted societies to doubt, distrust, discontent and to further divide populations and their governments. The ultimate goal is to undermine democracy – and in particular, the American variety, that Reagan-era “shining city on a hill” – and drive citizens to disengage.”