Part IV: Pursuing light-touch regulation of emerging industries

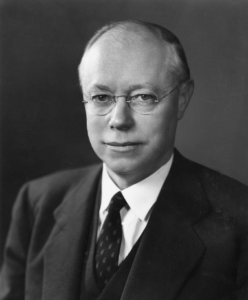

“The most necessary step to restoring prosperity is to restore freedom to individuals and businesses.”

– Senator Robert A. Taft, 1944

U.S. leaders arrived at a bipartisan consensus between 1944 and 1949 that favored light-touch regulation of emerging industries rather than heavy-handed central planning policies. The framework they built during those years diverged dramatically from those of every peer nation and created a large advantage over other countries in the degree of economic freedom it allows to individuals and businesses. The decisions America made in those years have played a pivotal role in the nation’s persistent edge over peer nations in productivity, incomes, and living standards.

This essay is the fourth in a six-part George W. Bush Institute-SMU Economic Growth Initiative series on how America’s distinctive model for innovation and economic growth came to be. The policy decisions of the late 1940s were far from inevitable. They represented an improbable but decisive break with the main policy directions of the New Deal and World War II eras.

We emphasize regulation of emerging industries specifically because new industries have played an outsized role in America’s outperformance relative to other countries. “Standout firms” – mostly fast-growing companies in young industries – accounted for almost four fifths of the nation’s edge over European nations in productivity growth over a recent eight-year period, though they made up only 5 percent of firms, according to a 2025 McKinsey Global Institute study.

Free markets versus central planning before 1939

Until the advent of the Great Depression in 1929, America had a rich history of giving wide rein to free enterprise and new technologies. Several industries saw explosive growth during the booming 1920s, including radio, automobiles, aviation, residential power, and health insurance. Federal policymakers considered, but rejected, having the public sector play a large role in each of these industries.

The Depression, however, led many people around the world to conclude that free markets had failed. It became commonplace among thinkers like the English economist John Maynard Keynes and many ordinary Americans to dismiss free markets as a discredited relic of the 19th century that would never return. Some argued that much greater state-directed central planning of the economy was both desirable and inevitable. Very few people understood what has now become the dominant view among economic historians: that the Great Depression resulted from wrong-headed monetary policies, not market failures.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt seems to have subscribed to his era’s fashionable anti-market views. When a senior advisor helping prepare a speech asked FDR about some strongly worded criticisms of free market capitalism in the draft, the president replied, “If that philosophy hadn’t proved to be bankrupt, Herbert Hoover would be sitting here right now,” historian H.W. Brands recounts in Traitor to His Class: The Privileged Life and Radical Presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Most of Roosevelt’s advisors were central planning advocates. Rexford Tugwell, a senior member of FDR’s “brain trust,” ridiculed Adam Smith’s idea that markets worked “as if guided by an invisible hand.”

“The cat is out of the bag,” Tugwell wrote. “There is no invisible hand.” Governments needed to provide “a real and visible guiding hand,” he argued. Like other advisors, Tugwell expressed admiration for the Soviet Union under its dictator Josef Stalin: “The future is becoming visible in Russia,” he said.

Several of the key initiatives within FDR’s New Deal reform program amounted to significant leaps toward central planning. The most important was the National Industrial Recovery Act, which established a powerful new agency, the National Recovery Administration (NRA), to oversee wages, prices, and production in every major industry. Central planning initiatives also included the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), the National Resources Planning Board, and the Wagner-Steagall Act’s funding program for new local public sector housing developers. No senior administration figure suggested that any of these initiatives should sunset once America’s economy recovered from the Depression.

America still had prominent advocates for market capitalism in the 1930s. A group including top-level corporate CEOs as well as Al Smith, FDR’s predecessor as New York’s governor, launched a group called the Liberty League to oppose New Deal central planning measures. “NRA!” Smith intoned during a 1936 speech, referring to FDR’s planning agency. He argued that the NRA was “an octopus set up by government that wound its arms around all the business of the country, and choked little business to death.”

But on the eve of World War II, thoughtful observers would have concluded that Smith represented a dying mindset and predicted the triumph of central planning in economies everywhere.

Central planning during and after World War II

The war years saw the federal government assume unprecedented powers over the private sector economy. The Roosevelt Administration established a veritable alphabet soup of planning agencies, such as the War Production Board, the Office of War Mobilization, and the Office of Price Administration. These and other federal agencies implemented a central planning regime more comprehensive than any other Western democratic nation has ever attempted.

America’s war mobilization succeeded by any measure. By 1944, the U.S. economy was producing more than twice as much output per worker as Germany’s economy and more than five times that of Japan. War factories accomplished staggering feats, as Alan Greenspan and Adrian Wooldridge describe in Capitalism in America: A History. Ford Motor Co.’s Willow Run plant quintupled aircraft output from 1943 to 1944. Henry Kaiser’s West Coast shipyards slashed the time it took to build a Liberty ship by 95% over the course of the war. War mobilization plus the induction of 16 million Americans into the military largely ended unemployment, which hadn’t dipped below 10% of the workforce in more than a decade.

These successes led many to conclude that the federal government should carry over its central planning activities to peacetime. In his 1944 State of the Union address, Roosevelt called for a far larger state role in the postwar economy than had ever prevailed before 1941. In 1944, he announced his support for new federally owned entities like the TVA to take over provision of electricity, water, and other key industries in the Missouri River Valley, the Columbia River Valley, and elsewhere.

Other leading figures echoed these views in 1945. Chester Bowles, Director of the Office of Price Administration, called for extending the wartime system of wage and price controls indefinitely into peacetime. The White House’s chief economist pushed hard to establish a government-owned and managed venture capital agency that would guide technological progress and back preferred firms. Liberal New Dealers in Congress tried to create an agency within the Department of Commerce to direct private-sector research and development on production processes. When Japan surrendered in September 1945, ending the war, there was every reason to believe that the United States would adopt some or all these proposals.

Free market champions push back: Robert Taft and his allies

Between 1945 and 1946, the political tides unexpectedly turned against central planning and toward market capitalism, putting America on a policy path entirely unlike that pursued by any peer nation. More than anyone else, the leader responsible for this tectonic shift was Ohio Senator Robert Taft.

The son of President William Howard Taft, Robert A. Taft was born in 1889. He graduated first in his class at the Taft School (founded by his uncle), Yale College, and Harvard Law School. He served in the Ohio Legislature for several years in the 1920s, then left to become a top private sector lawyer. In 1938, dismayed by the direction of the country, he entered the race for a U.S. Senate seat. Few thought he had much chance as his pro-market views were out of step with the times, but he won an upset victory. From his arrival in Washington until his death in office in 1953, his intellect, work ethic, and convictions made him the unofficial but universally recognized leader of the Republican Party in Congress.

During 14 years in the Senate, Taft was America’s most prominent advocate for limited government and free markets. He consistently argued, as he said in a 1946 speech included in his private papers, that “the private enterprise system, through the incentives and rewards which it affords, gives life and progress to the economic system and produces a higher average income than any other system in the world.” By contrast, central planning removed the “incentive to use brains, to save money, to work,” he believed.

As World War II approached its end in late 1944 and 1945, Taft traveled the country, making the case that America faced one of the most momentous choices in its history. Americans would soon have to decide between central planning in the postwar world and “the basic system under which this country has prospered for 150 years,” he said. Taft defended market capitalism not as a return to a mythical past, but as the best path for building a future of technological progress and rising living standards.

He also believed, contrary to historical narratives that portray him as an antigovernment reactionary, that the federal government would have a vital – though limited – role to play in providing base levels of income, housing, education, and health care for low-income families. He was, moreover, ahead of his time in his strong support for civil rights measures to end racial segregation and other injustices.

Historians sometimes criticize Taft for his non-interventionist views on foreign affairs between 1939 and 1941. Like most Congressional Republicans, he believed (with reasonable justification) that Roosevelt was working to steer the United States into World War II while insisting he was not. Taft pressed for rearmament starting in the late 1930s and vigorously supported FDR’s conduct of the war after Pearl Harbor, but it’s plausible that he underestimated the threat posed by Nazi Germany and the case for intervention.

By 1946, Taft had influential allies. That year, the Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek, then living in England, published his book The Road to Serfdom. While the book received little attention in the U.K., Hayek’s tour to promote it in America became a surprise media sensation. Hayek argued that socialist central planning tended to undermine democratic norms and end in tyranny. He also made what became a classic argument: that central planning would lead to disastrous economic outcomes over time because central planners could not possibly gather enough information to micromanage the economy effectively.

In addition, a group of U.S. business leaders launched a media campaign making the case that federal planning measures posed a threat to the nation’s postwar recovery and long-term prosperity. A key figure was former Studebaker CEO Paul Hoffman, who would go on to become the chief administrator of the Marshall Plan, America’s historic initiative to aid the recovery of war-ravaged Europe.

The emergence of a uniquely American consensus

Between 1944 and 1952, light-touch regulation of emerging industries went from being a quixotic idea endorsed only by true believers like Taft to near-universal consensus in the United States. This historic sea change started late in the war years, when Taft and his free-market allies pulled together enough votes to shut down the National Resources Planning Board and several other planning agencies.

Taft then waged a three-year campaign to end the federal price control regime, as historian James Patterson documents in Mr. Republican: A Biography of Robert A. Taft. Most Americans believed in 1944 and 1945 that ending price controls would ignite ruinous inflation. But Taft persuaded people that the price control system was responsible for shortages of products ranging from houses to meat, since it created bad incentives for producers. Shortages, he convinced voters, were the true root of inflation. The answer was free markets and abundant production. Harry Truman, President after FDR’s death in April 1945, reluctantly agreed to end price controls at the start of November 1946 in an effort to win the midterm elections, which were just days away.

But it was too late. Voters, embracing the campaign slogan “Had enough? Vote Republican,” gave Republicans decisive majorities in both houses of Congress. Taft and his allies were now positioned to implement market-oriented policies across a host of issues. Meanwhile, 1946 and 1947 saw the exit of several prominent New Dealers from the Truman Administration, such as Henry Wallace, Vice President during FDR’s third term and then Commerce Secretary. Democratic Party thinking on how the state should best support broad-based prosperity evolved toward less intrusive policies aimed at managing the economy through interest rates and fiscal policy and away from central planning measures.

In 1948, Truman shocked pundits by winning reelection. Democrats took back Congress as well, but their interest in central planning measures had faded. Central planning effectively died as a serious consideration in American politics with the 1950 outbreak of the Korean War and the 1952 election of moderate Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower as president.

European nations went in the opposite direction. “Nobody in Europe believes in the American way of life – that is, in private enterprise,” the English historian A.J.P. Taylor wrote in late 1945. Britain’s delegation to the first-ever conference on multilateral trade liberalization in 1947 told U.S. counterparts that America was “alone in its belief that free enterprise can be a wise or even a major rule for the conduct of economic affairs.… We must all move towards some intermediate system,” State Department cables document.

The U.K., under Prime Minister Clement Atlee and the Labour Party, seized control of major industries in the late 1940s in the name of socialism. France – where the Communist Party won more than 26% of votes in the nation’s first postwar election and joined the governing coalition – pursued a similar course. Germany’s nascent government, led by the moderate Konrad Adenauer and still under Allied occupation, aimed for a middle path between democratic socialism and heavily regulated market capitalism.

Emerging industries: Three case studies

The effects of America’s turn toward light-touch policies are most visible in the paths followed by several specific sectors. Consider three: mass-produced housing, health care, and television.

Mass-produced housing: America emerged from 16 years of depression and war with a housing shortfall of about 6 million units, Taft estimated. Another 6 million were hopelessly dilapidated and needed to be replaced. Progressive New Dealers proposed in 1945 and 1946 to create an ecosystem of federally funded but local government-controlled housing developers to address the challenge.

Taft and his allies rejected this idea. Instead, America pursued three policies that spawned an enormous new industry of large-scale community developers.

First, the GI Bill of 1944 provided generous mortgage loan guarantees to World War II veterans. Crucially, loans followed the veteran, so the policy provided a huge boost to housing demand in whatever locations proved attractive to veterans and their families. Postwar legislation sponsored by Taft reinforced these effects by expanding the Depression-era Federal Housing Administration’s loan guarantee program, helping veterans and nonveterans alike.

Second, Taft’s 1949 housing legislation subsidized development by public sector housing authorities but restricted the program to low-income families. This measure promoted growth of a private sector real estate industry that otherwise would have been undercut by public sector authorities – though it also had the unintended side effect of creating local government-owned housing “projects” that became known for concentrated poverty and urban decay.

Third, private sector real estate organizations succeeded in blocking local proposals to empower public sector planning authorities in ways that would have slowed the rollout of master-planned communities in suburban areas, such as the large developments built by William Levitt on Long Island, New York, and elsewhere, Marc Weiss recounts in The Rise of Community Builders.

By contrast, postwar governments in Germany, France, the U.K., and Japan mostly addressed deep housing shortages by building up public or quasi-public housing authorities as developers and landlords.

America’s policies resulted in more than 15 million new homes between 1949 and 1959, easily surpassing Taft’s estimate of the total need. Each of the four peer countries fell short relative to estimated needs during the same period. Over the four decades from 1950 to 1990, the United States added enough housing to keep up with the nation’s population growth and provide for normal replacement of obsolete homes. House prices consequently remained at relatively affordable levels, providing a powerful springboard for upward mobility. America also created a hugely successful homebuilding industry that became one of the nation’s largest employers.

Health care: Taft and his allies were also responsible for policies that created a very different health care system than the ones that developed in Europe, Canada, and Japan. Most important, they rejected proposals by the Truman Administration to create a system of compulsory government health care insurance. Taft called for a new system of government-provided insurance for lower-income families, similar to what came into being in 1965 through the Medicaid program. Free-market leaders also endorsed policies to support the buildout of modern hospitals under the 1946 Hill-Burton Act, but kept the federal government out of operating or regulating local hospitals.

Congress additionally promoted the growth of the pharmaceutical industry by enshrining the right of inventors to patent new drugs, providing a light-touch path for product approvals, and avoiding price controls. Together with America’s postwar commitment to medical research funding through the National Institutes of Health, these policies created near-perfect conditions for the rise of a globally dominant biopharmaceutical industry, as economic historian Peter Temin recounts in Take Your Medicine: Drug Regulation in the United States.

Most European countries adopted government-directed single-payer health insurance systems and gave public-sector agencies a larger role in hospital development than in the United States. The U.K. went further, nationalizing virtually all health care services under the country’s National Health Service.

As a result of these differences, the United States built a health care system that provides far more abundant medical resources for its citizens than that of any peer country. The main tradeoffs Americans have faced because of their private sector-led system are higher prices for drugs and services than in peer societies and patchy insurance coverage for lower-income people.

Television: Broadcast television was the most exciting new consumer service of the early postwar years. As they had with radio in the 1920s, policymakers considered proposals to regulate the industry’s content or micromanage its technology choices. But again, a market-oriented Congress decided against these ideas, as Christopher Sterling and John Kitross show in Stay Tuned: A Concise History of American Broadcasting. Fueled by the rise of popular content like the shows I Love Lucy, Dragnet, and The Lone Ranger, television saw the fastest growth of any consumer product in America’s history to that time.

By contrast, European countries as well as Canada established government-controlled monopoly broadcasters. Partly as a result, they experienced much slower growth in adoption of the new product.

America’s fast television launch helped the nation build on its dominant global position in media content, which was already strong as a result of Hollywood’s success in movies. This self-reinforcing success not only created a great American industry but also became a form of “soft power” for the United States as people around the world grew fascinated by what they saw in U.S.-produced shows and films.

Six decades of free market policies deliver as promised

America’s pattern of light-touch regulation repeated itself with many emerging industries over later decades, including semiconductors, computers, internet services, biotechnology, oil and gas production from shale, and now artificial intelligence. In each of these industries, the United States has dominated innovation and entrepreneurship in the industry’s high-growth early years.

Some peers – notably Japan and France – have pursued state-directed industrial policies aimed at catching up to the United States in targeted industries, especially from 1950 to 1990. While most initiatives failed, some proved effective at winning significant global market shares in industries that had grown mature in the United States. Japan, for instance, pulled ahead in commodity memory chips in the 1980s.

But central planning policies have not created large new industries in any of these countries. Nor have they generated superior cutting-edge innovation in existing industries still in their high-growth stage. If anything, America’s lead in frontline innovation has grown more pronounced in the 21st century, as its dominant positions in biotechnology and AI attest.

Since the 1980s, America has periodically made forays into centrally planned industrial policies. These included initiatives to promote next-generation semiconductor production processes through the Sematech consortium in the late 1980s and cutting-edge solar panels through the government-backed firm Solyndra in the 2010s. Neither of these proved successful.

On the contrary, U.S. policies toward emerging industries have worked best when they focused on basic science, STEM education and training, and quality infrastructure – and otherwise stayed out of the way of private sector innovators – as economists Gary Clyde Hufbauer of the Peterson Institute for International Economics and Eujin Jung of the World Bank show in a 2021 study of American industrial policies.

More generally, the United States has consistently held a commanding lead over most wealthy peer countries for regulatory restraint, based on an index maintained for more than 50 years by scholars at Canada’s Fraser Institute and SMU’s Bridwell Institute for Economic Freedom.

Despite their stunning successes, the principles of limited government and democratic capitalism have become less popular in America in recent years. Ironically, this reflects frustrations over problems resulting not from free markets but from bad policies. These include unaffordable home prices, caused by policies that make it too hard to build new homes, and high college tuition, attributable to weak innovation by universities protected from competition by high regulatory entry barriers.

But history leaves no doubt: Free-market principles – including light-touch regulation of breakthrough industries – are a main reason that Americans enjoy far higher living standards than their peers in other countries today. Adapt them to our time, but don’t reject them.