Part V: Opening up markets through international trade

“America’s stake in the world’s trade means much more to us than a great expansion in peacetime production and employment. It represents a great new hope of peace for America and for the world.”

– Will Clayton, 1943

Between 1944 and 1952, America led historic initiatives to rebuild the war-ravaged economies of Western Europe and to conclude the world’s first multilateral trade liberalization treaty. These policies succeeded beyond the expectations of even their most enthusiastic champions. They put the world on a path to six decades of explosive growth in international trade, helping lift billions of people from poverty around the world. They also contributed powerfully to economic growth and opportunity in the United States.

This essay is the fifth in a six-part George W. Bush Institute-SMU Economic Growth Initiative series on how America’s distinctive model for innovation and economic growth came to be. If other policies we describe in this series were far from inevitable, America’s decision to lead much of the world toward open, rules-based trade was downright improbable. It represented a reversal of 150 years of U.S. economic policy that virtually no one thought possible in 1944.

The benefits to America of trade openness reflect a simple economic principle: Trade helps each country specialize at what it does best. Because America has stood at the forefront of innovation throughout the 80 years since World War II, trade has strengthened the nation’s most innovative industries and firms.

Greater trade openness has been overwhelmingly positive for the American people, though it has weakened some older industries in which the United States is a net importer. America’s relatively market friendly policies have allowed people and resources to shift to the nation’s most competitive industries from declining ones. World-leading export firms, moreover, pay considerably better than firms in less competitive industries. Giving people the opportunity to buy goods from the world’s most efficient producers has also helped all Americans, freeing up purchasing power that has supported the growth of new industries within the United States.

American trade policy before 1944

The United States was a high-tariff country from the early 1800s through World War II, with relatively modest participation in world trade. America’s average tariff rate fluctuated wildly throughout the nation’s first century and a half but was never lower than 15% as a share of imports – other than during a brief period before World War I – Dartmouth University economist Douglas Irwin shows in his book Clashing Over Commerce: A History of U.S. Trade Policy. Average tariff rates peaked at about 55% in the 1820s. If tariffs were extremely high then, it’s worth noting that the United States had no income tax and imports represented a small share of consumer spending, so overall taxes were very low by today’s standards.

The main driver of changing tariff rates was domestic politics. The Democratic Party, representing the agrarian South, mostly favored lower tariffs as a means of gaining greater access to foreign markets for Southern cotton and other agricultural goods, America’s main exports throughout the period. The Republican Party – and its predecessor the Whig Party – represented the industrial North and consistently called for high tariffs.

Republicans passed two large tariff increases during the years between the two world wars, including the infamous 1930 Smoot-Hawley tariff, which most economists believe contributed to the Great Depression. Smoot-Hawley, which triggered a wave of retaliatory tariff increases around the world, led not only to a downward spiral in trade but also a vicious cycle of worsening distrust among Western nations that undermined efforts to mount a collective stand against Adolf Hitler’s Germany.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, elected in 1932, had little interest in trade and was the first Democratic president in a century who didn’t pursue legislation to lower trade barriers unilaterally after taking office. This reflected both the difficult politics of reducing import protection during the Great Depression and a shift away from trade openness in Democratic Party thinking. Roosevelt’s top economic advisors were believers in state-led central planning who viewed free trade as well as light-touch regulation of business as a discredited 19th century relic. They thought government should actively manage trade, as historian Charles Kindleberger shows in his classic account The World in Depression, 1929-1939.

FDR did appoint an ardent supporter of free and fair trade, Cordell Hull, as Secretary of State. A longtime Tennessee congressman, Hull held the traditional Southern view of trade but also the strong conviction that international trade promoted peace among nations. At Hull’s urging – and with tepid support from FDR – Congress passed the 1934 Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act (RTAA), empowering the president to implement modest tariff reductions in return for negotiated trade opening by other countries.

Hull reached agreements with a few smaller countries, resulting in modest declines in U.S. tariffs. But RTAA allowed for only small tariff cuts and imposed onerous steps before any change, ensuring its effects were small. Roosevelt, moreover, delegated little authority to the courtly Southerner Hull, with whom he never had a close relationship. FDR’s advisors as well as members of Congress from both parties ridiculed Hull behind his back as a throwback to an earlier time. Foreign barriers to U.S. exports grew steeper over the 1930s as Britain and other countries withdrew into tightly controlled trading blocs. The general trend of the decade was toward a continuing collapse of world trade.

Envisioning the post-World War II world

In 1944, a handful of U.S. policymakers started thinking seriously about the postwar world economy. The overriding realities as World War II approached its close were the devastation of much of Europe and Asia and America’s overwhelming economic dominance. By late in the war, the United States accounted for more than half the world’s total industrial production. America stood “at the summit of the world,” as British Prime Minister Winston Churchill put it in a 1945 speech shortly after leaving office. European nations, on the other hand, would face daunting challenges rebuilding their physical infrastructure and would potentially be unable to deliver significant exports or buy many American goods for years to come.

Against this backdrop, Hull created a planning group within the State Department to consider trade policy options. Hull had extracted a promise from Churchill that Britain would engage in a good-faith effort at postwar mutual trade liberalization as a condition for American wartime assistance under the Roosevelt Administration’s 1941 Lend-Lease Act. This promise created an opening, but by 1944, prospects for trade liberalization didn’t look good.

Several unfamiliar political forces – in addition to the State Department’s midlevel planners – created momentum behind the idea of launching an initiative to open international trade. The nation’s leading industrial firms were now so large that they could only realize significant growth in the postwar world through exports. They understood they could not increase exports unless America allowed other countries to earn dollars by selling to the United States. As a result, voices for industry like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the National Association of Manufacturers for the first time expressed cautious support for trade liberalization. So did a handful of Republican legislators, as the papers of Senator Robert Taft show.

Another new factor was a growing sense that America had failed to live up to its international responsibilities in the aftermath of World War I and must not repeat this mistake. The House of Representatives Ways and Means Committee reported in an early 1945 statement on trade policy that its members were “struck with the parallel which exists between the situation in which we find ourselves now and the situation at the end of the last war,” as Irwin recounts in his book.

The United States, the committee wrote, had rejected “liberal and enlightened” trade policies after World War I “with disastrous consequences.” After World War II, there would be “no other country capable of offering effective leadership in the conditions of economic uncertainty which will prevail,” so America must invest its “tremendous economic power and prestige” in efforts to build a prosperous postwar world.

But trade opening proposals faced powerful resistance. Roosevelt and his central planning-minded advisors made no effort to support Hull’s plans. Hull’s relationship with FDR had grown frosty as a result of Roosevelt’s exclusion of his Secretary of State from most wartime diplomacy. Liberal Democrats and Republicans in Congress mostly opposed trade opening. Smaller manufacturing firms continued to demand high tariffs. Agricultural interests started shifting toward support for import protection for the first time in America’s history, fearing a surge of imports from countries like Australia and Brazil.

Most importantly, few foreign governments were interested in the project. Britain, France, and other European countries believed they would not be able to ramp up exports for years, so allowing greater American imports would drain precious foreign exchange reserves and bankrupt them.

In the U.K., a polyglot coalition vehemently opposed trade opening. Nostalgic imperialists defended the imperial preference system that had emerged during the 1930s – favoring imports from countries that had been part of the British Empire over imports from America and other nations – as a vital measure for preserving the Empire. Labour Party leaders saw state-managed trade as a key component of building socialism after the war. Gloomy British Treasury officials believed strict central planning of all aspects of the economy was the only way Britain could get back on its feet. John Maynard Keynes, the world’s most famous economist, dismissed free trade as “the clutch” of a “dead hand” from the 19th century and mocked the “lunatic proposals of Mr. Hull,” as his biographer Robert Skidelsky recounts.

In November 1944, Hull retired, pessimistic about prospects for trade opening. He was by this time “a very ill man,” recalled Dean Acheson, then an Assistant Secretary of State. Another official said of Hull, “He was tired of intrigue, tired of being bypassed, tired of fighting battles which were not appreciated. The end of a long career is at hand – ending not in satisfaction, as it should, but in bitterness.”

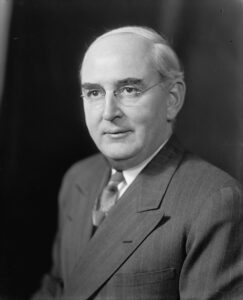

Two leaders who helped build the postwar world economy: Will Clayton and Arthur Vandenberg

The leader who turned the tide, more than anyone else, was Will Clayton. Born in Tupelo, Mississippi, Clayton left school after eighth grade for lack of money and joined a cotton-trading business. In his 20s, he left to form his own firm alongside two relatives: Anderson, Clayton, and Company, in Houston. By the 1920s, it was the world’s largest cotton-marketing enterprise, and Clayton was among America’s most prominent business leaders. During the 1930s, he was one of the strongest voices in the U.S. business community calling for rearmament and support for Western nations confronting the German threat.

In 1941, Clayton became one of the foremost “dollar-a-year” businessmen – industry leaders who went to Washington to help manage America’s wartime economic mobilization for very little salary. His principal responsibility was running the government’s efforts to buy up raw materials around the world for war production and deny them to the Axis powers. As a side assignment, he served as the Commerce Department’s representative on the team negotiating the Bretton Woods agreement, which would govern the postwar world monetary system.

In November 1944, FDR nominated Clayton to become Assistant Secretary of State with a mandate to develop plans for the postwar world economy. For the next three years, Clayton was the chief architect of America’s foreign economic policies. He played a singular role in shaping a series of monumental policy initiatives, since no one ranking above him for those three years – Roosevelt, President Harry Truman, or any of the three Secretaries of State and two Undersecretaries with whom he served – knew much about international economic affairs. To a remarkable degree, they trusted him and gave him full authority.

Clayton shared Hull’s convictions on reviving trade as a vital part of building a more peaceful and prosperous world after World War II. But he brought strengths that Hull had never had: intimate knowledge of how international commerce really worked, extraordinary negotiating skill, and a unique talent for explaining the links between trade and American prosperity in ways everyone could understand.

During 1945, Clayton convinced Truman and other top leaders that America should pursue a multilateral trade-opening initiative. He also negotiated a $67 billion emergency loan to the U.K. (measured in 2025 dollars) – with Keynes on the other side of the table. The loan agreement required a reluctant British government to participate in U.S.-led trade negotiations over the next two years.

To move forward, Clayton needed the support of Congress as well. It was essential, moreover, to have Republican support, since congressional Democrats were now too divided on trade to pass the necessary legislation on a party-line basis. The key leader who made Clayton’s initiatives possible was Republican Senator Arthur Vandenberg of Michigan.

Vandenberg was elected to the Senate in 1928 after two decades as a prominent Michigan journalist. From the late 1930s until his death in office in 1951, he was the chief Republican foreign policy voice in Congress. Although he was an outspoken opponent of U.S. intervention in World War II before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, he changed his mind in the course of the war and became the leading congressional champion of U.S. international leadership in the early postwar years.

By 1945, Vandenberg had come to agree with Clayton on trade. Although Vandenberg represented a manufacturing-oriented state and had always favored high tariffs in the past, he now believed that trade opening was essential to America’s national interests in two respects: American prosperity would depend on greater two-way international trade, and American national security would depend on a rapid reconstruction of European countries that would only be possible if Europe rebuilt its export industries.

A whirlwind of negotiations, 1945-1947: The Marshall Plan and world trade opening

In 1946, Clayton persuaded a reluctant Secretary of State James Byrnes to propose an international trade conference, to be held the next year in Geneva, Switzerland. A pivotal moment came in February 1947, when Vandenberg promised Clayton his support in exchange for certain safeguards for U.S. manufacturers. Vandenberg played a decisive role in ensuring that Republicans – who had just won control of Congress – did not scuttle the Geneva talks. The Geneva conference got going in April.

In early 1947, Clayton also convinced his superiors that European countries needed a massive short-term infusion of financial assistance. Returning from a tour of war-ravaged Europe in May, he wrote a memorandum stating, “It is now obvious that we grossly underestimated the destruction to the European economy.” Clayton’s memo explained the need for an American-led European reconstruction program and sketched out a concrete plan. It created an immediate sense of urgency among top policymakers. Just after Clayton’s return, Secretary of State George Marshall called a meeting at which Clayton and other senior State Department officials worked out what became known as the Marshall Plan.

In Marshall’s speech at Harvard University announcing the proposal a few days later, the United States called on European nations to develop a shared reconstruction plan and present it to the United States. European nations desperate for help came together at a conference in Paris in July. This meant there were two interrelated conferences underway in Europe at the same time.

Clayton was the indispensable leader who ensured the success of these world-changing initiatives. Between April and October, he shuttled back and forth between Geneva, Paris, London, and Washington, effectively leading both conferences and going straight to top leaders in Britain, France, and his own government when negotiations threatened to break down.

Crucially, Clayton linked the two initiatives, telling Europeans he wouldn’t be able to sell the Marshall aid they so badly needed to Congress unless they agreed to trade concessions in Geneva. His position represented enlightened self-interest on the part of the United States. It used Marshall aid as leverage to extract trade concessions that would benefit U.S. firms and workers. But Clayton also understood that the Marshall Plan was just a stopgap measure to jump-start European reconstruction – and that Europe could only achieve sustained postwar prosperity through trade within the continent and with the United States.

At one point Marshall, concerned that the Paris conference might break down, sent Clayton a cable telling him to go softer in his trade demands at the Geneva meeting. When Clayton wrote back explaining his strategy, Marshall backed down and gave him his full support. Clayton effectively carried the weight of the postwar world economy on his shoulders for seven months in 1947.

By October, Clayton was able to report that both negotiations had come to a successful conclusion.

Approving the Marshall Plan, 1947-1948

Clayton still needed to win the support of Congress. His trade agreement didn’t require congressional approval, since Congress had already given the Truman Administration sufficient authority when it extended the RTAA in 1945. But the Marshall Plan represented an enormous financial commitment for the United States and could go forward only by an act of Congress.

Many lawmakers doubted the case for sending immense sums of American money to Europe when there were so many needs at home. Even Vandenberg, when he saw the size of the administration’s request, thought he had read the figures incorrectly. Marshall gave the proposal at best 50-50 odds, author Benn Steil writes in The Marshall Plan: Dawn of the Cold War.

Three factors convinced many members of Congress to throw their support behind the Marshall Plan. First, Clayton and other senior officials toured the nation explaining its importance to America’s prosperity and national security, generating a large positive shift in public opinion. Second, Vandenberg ran a tireless campaign to persuade his colleagues on Capitol Hill. Vandenberg was “just the whole show,” Marshall said. And third, Soviet actions in early 1948 – a communist coup overthrowing the democratically elected government of Czechoslovakia and imposition of a blockade on the western zones of occupied Berlin – persuaded leaders that Marshall aid was a necessary counter to communist aggression in Europe. The Marshall Plan passed overwhelmingly in April 1948.

Between 1948 and the Marshall Plan’s wind down in 1952, America provided Western nations – including Germany – about $230 billion, measured in 2025 dollars, amounting to an average of 1.5% of U.S. GDP each year. Marshall aid paid for capital goods imports from the United States that proved critical to Europe’s economic reconstruction. But more than its immediate economic effects, the Marshall Plan underwrote European political stability by instilling confidence that America would remain engaged as a trusted partner and promoting good working relations among Western European governments.

The Marshall Plan also made the Geneva trade agreement possible. Without Marshall aid, the world’s first multilateral trade opening treaty wouldn’t have stood a chance. The New York Times called the agreements of 1947 “the realization of Mr. Clayton’s dream: that a group of like-minded democratic nations could deliberately reverse the historical trend toward the strangulation of world trade. It is the big step that nobody but Mr. Clayton and a few of his colleagues thought would ever be taken.”

America’s leaders stay the course, 1949-2010

The United States played the leading role in eight more rounds of international trade negotiations from 1949 to 2008, each of which resulted in lower trade barriers around the world. The two most significant rounds in terms of tariff reductions were Clayton’s original Geneva round and a round launched by President John F. Kennedy – based on advice he received from a commission chaired by Clayton – and completed under President Lyndon B. Johnson. Republican Presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower and Ronald Reagan were particularly strong supporters of trade openness, continuing the reversal in Republican trade thinking that started with Arthur Vandenberg.

Over these decades, the average tariff rate on U.S. imports declined to 1% from 33% in 1944, Irwin’s book shows. The average rate imposed by wealthy trading partners on U.S. exporters fell to a similar level. Agreements reached in the 1970s and after went beyond trade in goods to reduce restrictions on services trade and strengthen intellectual property rights in other countries, disproportionately benefiting U.S. producers in view of their leading positions in sophisticated industries like software and biotech.

While growing trade openness enriched people throughout the world, it had particularly beneficial effects in the United States. By lowering barriers to U.S. exports, it vastly expanded the market for America’s most competitive firms. Trade not only helped American industries grow larger and create more high-paying jobs but also accelerated innovation. This is because firms at or near the technological frontier in their industries – American or foreign – mostly responded to enhanced foreign competition by strengthening their R&D capabilities, and the United States has long had an outsized share of companies operating at the technological front line, as the French economist Philippe Aghion and colleagues have shown.

Laying down the reins of world leadership?

U.S.-led initiatives to promote trade openness around the world largely petered out in the 2010s. The last multilateral trade negotiation, the Doha Round, came to an inconclusive end by 2017. The last bilateral agreements reducing barriers between America and other countries took place under President George W. Bush, with some of them ratified under President Barack Obama. The Obama Administration led negotiations to create a Trans-Pacific Partnership, but Democrats as well as Republicans turned against the agreement by the time of the 2016 presidential election. The next year, President Donald Trump formally withdrew the United States from the TPP.

America’s turn against open, rules-based trade starting in the 2010s resulted in part from growing public concerns about older manufacturing industries that have lost market share to foreign imports, particularly since China entered the World Trade Organization and secured low-tariff access to the American market in 2001. It also reflects popular misconceptions regarding the causes for declining employment in America’s manufacturing sector. The sector has shed jobs for several decades primarily because technological progress has made it possible to produce more goods than ever with less labor and because consumers have shifted their spending toward services like recreational travel as they’ve grown wealthier, economists overwhelmingly agree. Trade openness has played only a modest role.

Average tariff rates on U.S. imports doubled to about 2% during President Trump’s first term. The Biden Administration raised them slightly further. Nine months into the second Trump Administration, they stand at about 14%.

U.S. leadership in promoting world trade has never been uncontroversial. It has always faced opposition from older industries likely to suffer from greater trade openness. Even consumers and industries that stand to gain have rarely mobilized on its behalf. When America has made progress on the issue, it’s been because of resolute leadership from visionary Americans like Will Clayton and Arthur Vandenberg, plus strong presidential backing from leaders like Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Reagan.

But the international economic system built after World War II has contributed immeasurably to American prosperity for eight decades. America should preserve and build on it.