Investing in land ports of entry is an important and necessary step to maintain the global competitiveness of North America. However, we need more effective planning and financing for land ports of entry and to operate them more effectively to sustain and grow our competitiveness over the long term.

Border crossing infrastructure, an often overlooked but key factor in our economic competitiveness, got some attention from the Senate as part of the recent $1 trillion infrastructure bill that would also invest in U.S. roads, bridges, airports, and rail networks.

The bill includes $3.85 billion for construction and repairs to border stations and land ports of entry. Investing in land ports of entry is an important and necessary step to maintain the global competitiveness of North America. However, we need more effective planning and financing for land ports of entry and to operate them more effectively to sustain and grow our competitiveness over the long term.

On an average day, approximately $3.5 billion worth of goods move between the United States, Canada, and Mexico. Most of this freight – 63% – travels by truck across U.S. land ports of entry, so effective border-crossing infrastructure is critical to facilitate trade with our North American partners. When long lines at a border crossing stop goods from being transported, supply chains across the United States and North America are impacted. Moreover, these delays harm the U.S. economy.

For example, delays at the San Ysidro land port of entry between San Diego and Tijuana, Mexico, cost San Diego County $539 million per year in lost economic output and 2,900 jobs, according to a study conducted for the Bush Institute by the North American Research Partnership in 2016. The same study found that delays in San Diego cost the United States an additional $700 million in lost output and 5,000 lost jobs.

The funding provided in the Senate bill would be an important shot in the arm if it is enacted. But it is a fraction of the deferred maintenance required at our ports of entry, let alone the need for expanded and new border crossings.

The United States, Canada, and Mexico should create a trilateral working group to undertake holistic infrastructure planning. One aim of the group should be to gather more and better real-time data to inform decisions about infrastructure investment in the long term, as well as staffing and resource allocation in the near term.

The working group should also explore innovative financing options for border infrastructure projects, such as a North American border infrastructure bank. A border infrastructure bank could assist with coordination among local and federal governments on both sides of the border, as well as engage private capital to build responsive and sustainable systems for moving goods faster, cheaper, and more securely across North America.

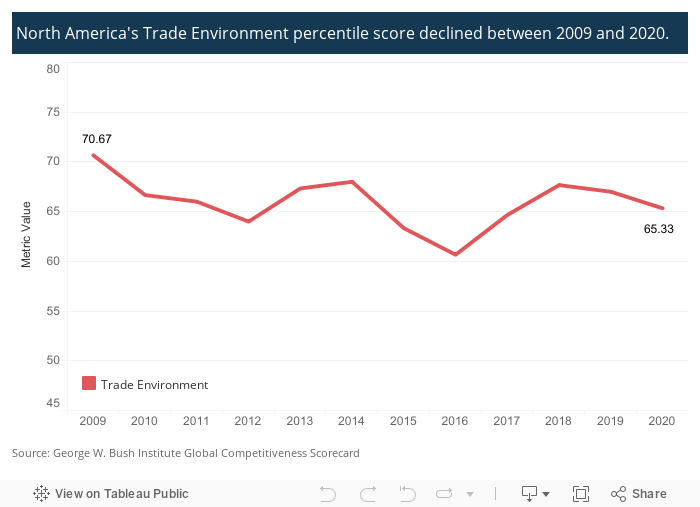

North America’s Trade Environment score on the Bush Institute’s Global Competitiveness Scorecard has declined over the past decade – to the 65th percentile in 2020 from 70th percentile in 2009. This drop reflects growing inefficiencies at the U.S.-Mexico and U.S.-Canada borders.

The World Bank (a Scorecard source) reports that North America’s percentile rank on the World Bank “trading across borders” indicator decreased 14% during the same period because other countries have been improve the efficiency of their borders, while North America has remained stagnant.

These declines demonstrate the need for holistic infrastructure planning across the region, including digitization of border processes and coordinated prescreening programs at the borders.

North American supply chains are spread out across the continent. The competitiveness of U.S. manufacturing, and of our economy as a whole, depends on our ability to trade with our neighbors efficiently over the long term.