Last summer, I became the first person in my family to set foot on Omaha Beach in 79 years.

Immediately, I was both captivated by the beauty of the French beaches and appalled by the destructive craters and bunkers that forever mark the events that occurred there on June 6, 1944. This was compounded with memories of my Paw Paw Ed and knowledge of his experiences on the same spot. One month after the D-Day landings in Normandy, my grandfather arrived on Omaha Beach as part of a clean-up crew that separated the German bodies from the Allied troops. The horrors of this experience stayed with him for the rest of his life.

This anniversary provides us with a valuable opportunity to not only remember our recent past, but to utilize our history as a guide to navigate where we are now. The horrors of war aren’t specific to World War II, yet humanity’s capacity for evil was on full display in a new way. Much of the evil that we attribute to WWII and, frankly, what we now see at home and abroad, disconnects the person from their God-given dignity and worth. That is exactly why we should pause to remember the 80th anniversary of D-Day, even amid the turmoil roiling the world.

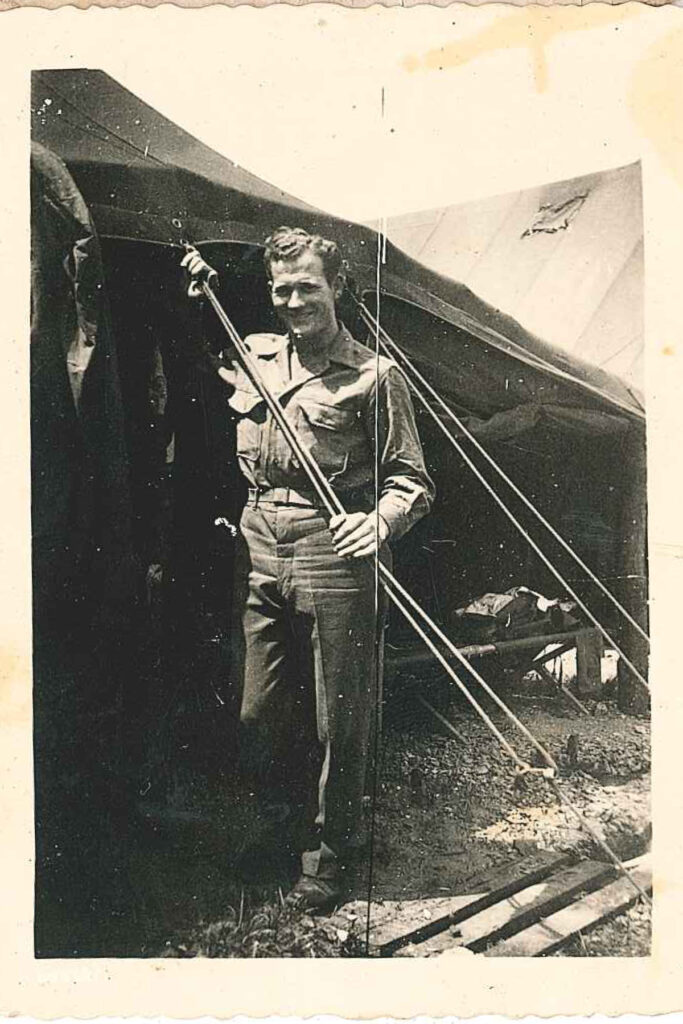

“When we arrived in Europe, I keep saying to myself what are we fighting for?” my grandfather wrote in one of my favorite entries in his journal. “One day I was in the Day Room and picked up this book and started looking at the pictures. I saw this picture of this fellow. Under the picture, it said his name was Abraham Lincoln, so I read what he said. He said, `Four score and seven years ago.’ It was then I realized what we were fighting for. All those rights, privileges that we cherish today. The right to be right where we are today.” My grandfather, Edgar Aucoin, joined the army at the age of 22 in March 1940, over a year and a half before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, bringing the United States into the war. In November 1942, he took the 12-day journey from New York to England by ship. He was stationed in Liverpool, in the south of England, where he guarded warehouses and a 12-story supply depot. Periodically, he helped with aid distribution across England. On June 6, 1944, his regiment was scattered around England on one of these trips, and his regiment didn’t return to the port city until two weeks after the D-Day invasion.

Over 150,000 Allied troops landed on five beaches in Normandy, in northern France, on D-Day, almost half of these troops were Americans. Many historians consider D-Day the turning point of the war, as Allied Forces finally gained footing in mainland Europe.More than 4,400 Allied soldiers were killed, including more than 2,500 Americans. An estimated 4,000 to 9,000 German troops were killed, wounded, or missing on D-Day alone.

When my grandfather arrived in France three weeks later, his first objective was to separate the bodies of the Allied soldiers from the Germans in an attempt to clean up the beaches. Understandably, he never discussed the experience, but it was clear that he was distressed by what he endured until the day he died at 95 in 2012.

“Amazed at destruction of cities, tanks, artillery pieces destroyed,” he wrote in his journal. “Rockets had destroyed whole city blocks used for storage and supplies. First small town, St. Joe, was destroyed and German tanks up and down the roads were all demolished.”

My grandfather often turned to recitation of poetry and speeches to process his experiences, including growing up in a large family in south Louisiana during the Great Depression and his wartime service. Throughout the war, he often overheard other men say, “he’s talking to himself again,” but reciting great works provided him with drive, determination, and often escape.

I had the privilege of sharing 15 years of life with my Paw Paw Ed. While I rarely ever heard him speak about his experiences, I did have the chance to hear him recite poem after poem and one of his favorite speeches, the Gettysburg Address. I probably heard him recite it close to 500 times.

It wasn’t until I had the opportunity to read his journals and postwar reflections that I discovered how he had used Lincoln’s speech about another bloody conflict to contextualize the one in which he was serving.

“We are met on a great battlefield of that war,” Lincoln said. “We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this…. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced.”

While, God willing, many of us will never be called to serve in a war, we must learn from the experiences of the Greatest Generation and be ready to defend freedom in our daily lives. We can do so by actively engaging in our communities, extending compassion and opportunity to those around us, voting in elections, and taking time to study history. One unique application I have learned from my grandfather is the lost art of memorization and recitation. This is a tangible way we can challenge ourselves by selecting speeches, verses, or poetry to meditate on and guide us.

Four score years ago, my grandfather, U.S. Army Staff Sgt. Edgar B. Aucoin of the 11Q Co 1st Battalion, 157th Infantry Regiment, was one of the lucky ones who made it home at the end of the war, and for this I am eternally grateful. He taught me the high price of freedom, and it’s one that none of us should ever forget.