Behind Shuttered Borders:

A view into North Korea's COVID-19 experiences

1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, in cooperation with the George W. Bush Institute, is to our knowledge the first published review of human rights abuses inside North Korea associated with the COVID-19 global pandemic.

The regime shut down its international borders and restricted internal travel from January 2020 until August 2023 – halting all exchanges related to trade, tourism, diplomacy, and humanitarian aid – and introduced a set of “anti-epidemic” rules that included strict internal quarantine measures.

As a result, the outside world had scant means to assess how everyday North Koreans fared during the three-and-a-half-year lockdown. The only information available came from the government, which declared during the first two years of the pandemic that the country had no positive cases of COVID-19 and touted its anti-epidemic efforts as “a shining success” of its socialist system. The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) later publicly acknowledged a COVID-19 outbreak for the first time in May 2022, reporting minimal deaths (74) and declaring “victory” over the virus only three months later.

This report is based on the voices of 100 ordinary DPRK residents amplified through micro-surveys conducted in the second half of 2023, just as the country’s lockdown restrictions and border controls were lifted.

Our report documents five major observations from these citizens about the government’s culpability and negligence in managing the pandemic:

- The North Korean government disseminated disinformation to its own citizens and to the world about the pandemic. Contrary to its statements to the World Health Organization (WHO) of “zero cases,” the pandemic raged in the country for more than two years before the regime admitted in May 2022 that the virus had permeated its borders.

- We believe that if the government had spoken truthfully about the pandemic and accepted outside help from 2020, many deaths could have been avoided. Survey respondents all noted increased access to COVID-19 testing and vaccines after May 2022 when Pyongyang admitted to cases of COVID-19 and reportedly accepted some assistance from China.

- Prior to the regime’s long-delayed announcement of an outbreak in May 2022, citizens reported having virtually no access to vaccines, no antiviral medications, and minimal supply of personal protective equipment. Moreover, lockdowns of markets and restrictions on internal movements exacerbated food and medicine shortages. It’s likely the national government dealt with the pandemic crisis by shirking responsibility and compelling the populace to fend for themselves. The government’s negligence was nothing short of abominable.

- The regime’s response to the pandemic also prevented individuals and officials at the local level from reporting symptomatic cases due to fear of censure and lockdown. This, in turn, intensified suffering as the pandemic spread.

- Efforts by the regime to use nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPI), defined as “anti-epidemic measures” (e.g., forced lockdowns, travel restrictions, market shutdowns), to strengthen authoritarian control over the citizenry simultaneously unearthed new sources of public resistance and potential regime vulnerability.

This report’s observations, based on a sample of 100 responses, should not be interpreted as a complete representation of views in North Korea. But they still provide the first glimpse into the experiences of ordinary North Koreans during the country’s most extreme period of isolation arguably in its history. Our observations are further informed by the North Korean regime’s well-documented track record of systemic human rights abuses and oppressive governance, as detailed by sources like Freedom House’s annual Freedom in the World Report, the U.S. State Department’s annual report on human rights practices, and the 2014 United Nations Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the DPRK.

For governments and international organizations seeking to improve the welfare of North Koreans, these observations about the pandemic lockdown can guide policies on a range of issues:

- Do not trust official DPRK statements or data at face value. Verify everything.

- Even if the North Korean government is likely to reject it, continue to offer humanitarian aid when needed.

- Devise and support legislative and nongovernmental organization initiatives to increase North Koreans’ access to accurate outside information.

- U.S. and allied governments working to prepare for potential DPRK regime collapse scenarios need to keep in mind that periods of increased authoritarian control can generate new, less visible sources of regime vulnerability.

- Continue to document evidence of human rights abuses to support future prosecutions of North Korean leaders.

2

INTRODUCTION

Generating a clear understanding of conditions inside the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK or North Korea) has always been a challenge. For decades, the so-called Hermit Kingdom has strictly limited movements of people, goods, and information across its borders, earning the moniker “the hardest of hard targets” among U.S. intelligence analysts

But the North Korean regime’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic brought the country’s opacity to new levels. The regime shut down its international borders from January 2020 until August 2023 – halting exchanges related to trade, tourism, diplomacy, and humanitarian aid – and introduced a set of “antiepidemic” rules that included strict internal quarantine measures. (Reports indicate that Pyongyang did accept limited Chinese support in 2022.)

As a result, the outside world had little means to understand and assess how everyday North Koreans fared during the COVID-19 lockdown. The only information available came from the government, which declared during the first two years of the pandemic that the country had no positive cases of COVID-19 and hailed its anti-epidemic efforts as “a shining success” of its socialist system. The DPRK later publicly acknowledged a COVID-19 outbreak for the first time in May 2022, reporting minimal deaths (74) and declaring “victory” over the virus only three months later. This unusual transparency may suggest that the severity of the COVID-19 outbreak, particularly in Pyongyang, made containment impossible, prompting the leadership to acknowledge cases to reassure the public and demonstrate control over the crisis.

Such pronouncements by the DPRK would normally be regarded as disingenuous and meaningless. However, the COVID-19 information vacuum has potentially greater significance for the world than the typical DPRK obfuscations. The global health community lacks a clear grasp of the degree to which COVID-19 spread within North Korea and whether it might be a breeding ground for new variants given the already dire lack of health care, poor nutrition, rampant disease (e.g., tuberculosis), and weak vaccine infrastructure. In addition, human rights advocates lack a clear sense of how much Pyongyang used the pandemic to justify new forms and levels of oppression.

This report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, in cooperation with the George W. Bush Institute, is to our knowledge the first published review of what happened inside North Korea during the global pandemic. It is based on the voices of 100 ordinary DPRK residents amplified through microsurveys conducted in the second half of 2021, just as the country’s lockdown restrictions and border controls were lifted.

3

HOW THE QUESTIONNAIRES WERE CONDUCTED

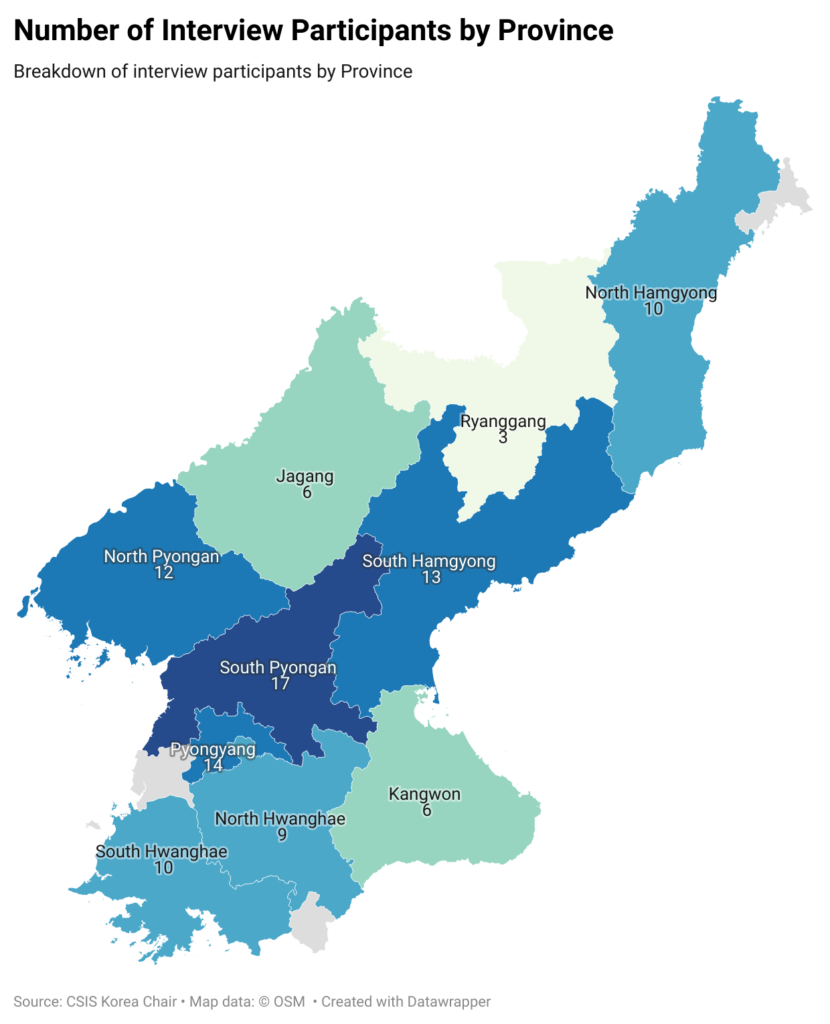

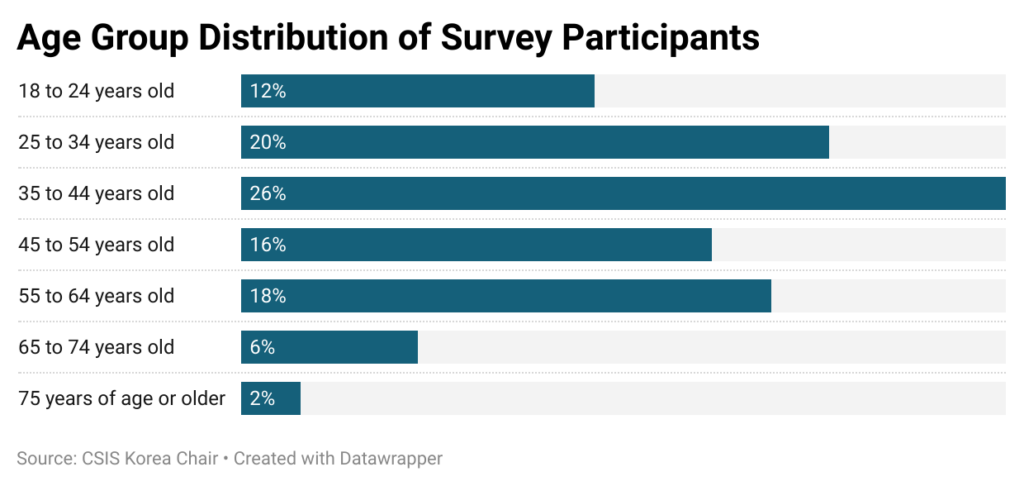

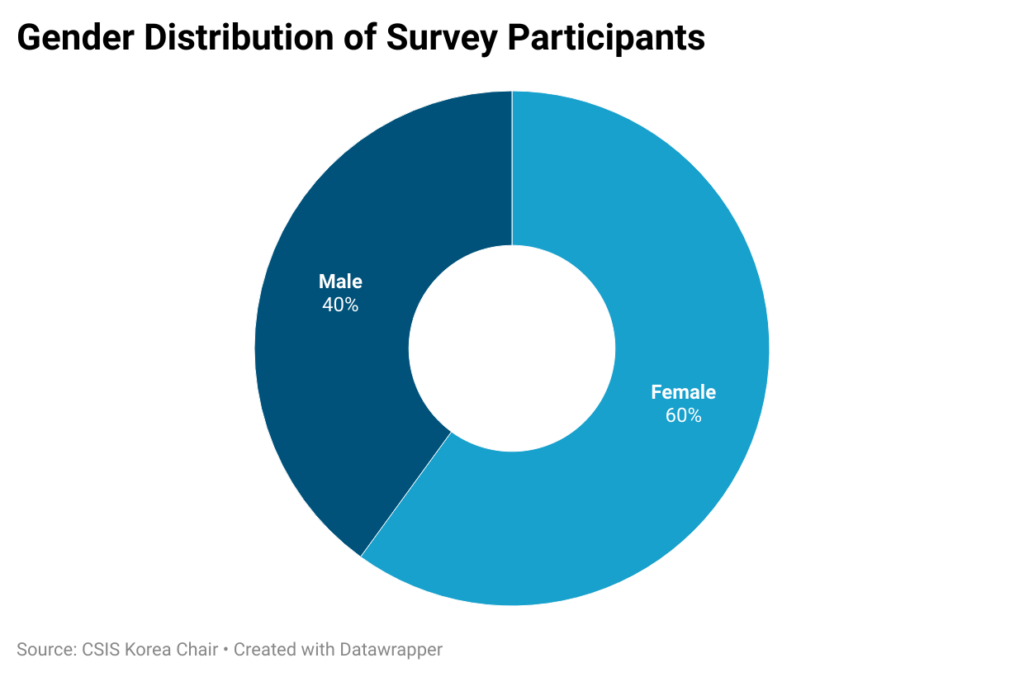

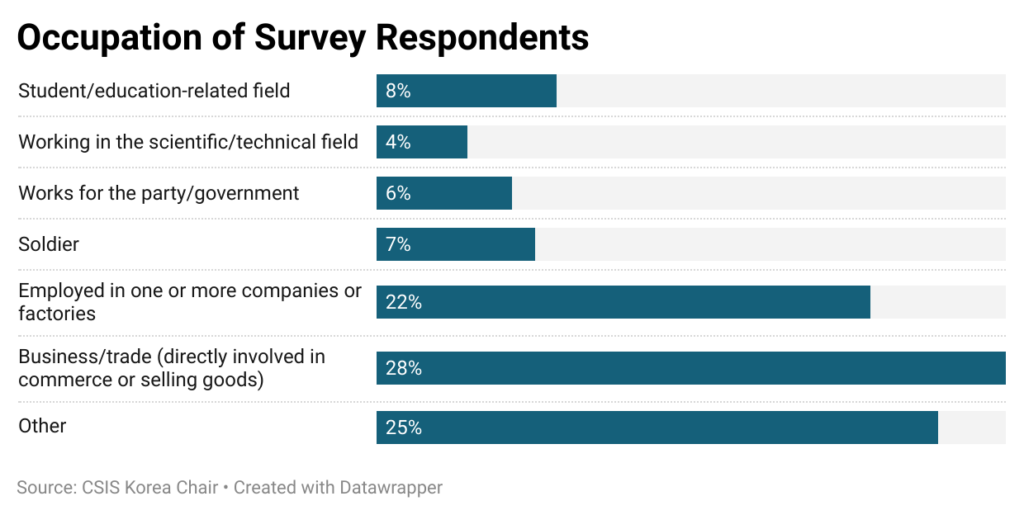

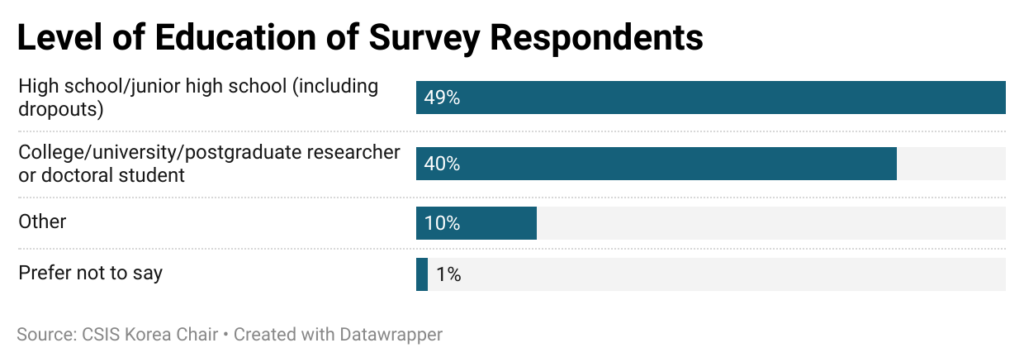

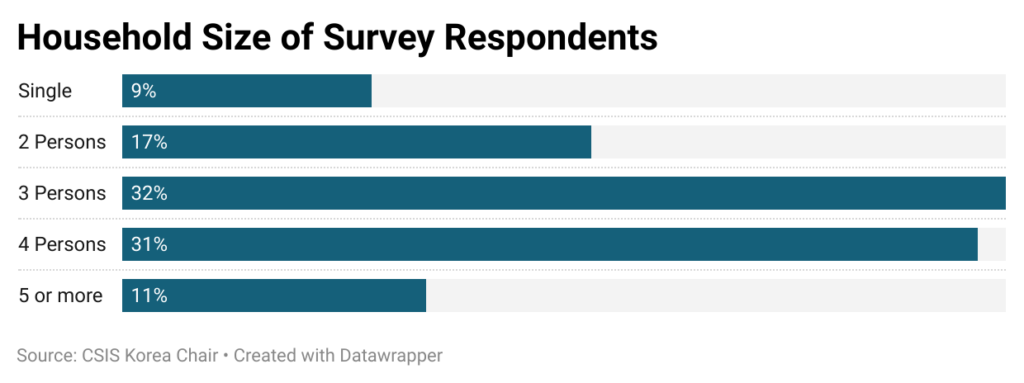

We partnered with an organization that has a successful track record of managing discrete and careful questionnaires in North Korea. The interviews were conducted during the second half of 2023, with the survey in the field from September to December 2023. Our total survey population was 100 North Koreans living in the country. Interviewees consisted of 60 females and 40 males and represented a wide range of ages, occupations, household sizes, and education levels. Geographically, respondents were also divided across North Korea’s nine provinces and the capital city of Pyongyang.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

The questionnaires were conducted through casual, in-person conversations between interviewers and respondents. The interviewers were carefully trained to avoid leading questions or prompting specific responses to protect the integrity of the survey and the safety of all participants (see sample questionnaire in the appendix). The interviewers used “snowball sampling” to conduct the conversation, which involves a main group of informants bringing in additional participants. This method would not be considered ideal under normal circumstances, as it does not constitute random sampling and therefore cannot mitigate the risk of several forms of bias being introduced into the data when participants may know one another or share common experiences, political attitudes, socioeconomic backgrounds, etc., but conditions in North Korea are far from normal.*

Overall, the interviewers prioritized the safety of the participants in considering their methodology, as no one could protect survey participants if the government found out about their activities. For this reason, this report does not reveal information that could identify participants. Due to these sampling constraints, this report’s observations should not be interpreted as a complete representation of views in North Korea. In addition, the absence of a testing regime and lack of communication by the government (discussed below), means that citizens’ reporting of their challenges in dealing with COVID-19 were based on their own assumptions about, rather than confirmation of, the virus. But they still provide the first glimpse into the experiences of ordinary North Koreans during the country’s most extreme period of isolation arguably in its history.

Our observations are further informed by the North Korean regime’s well-documented track record of systemic human rights abuses and oppressive governance as detailed by sources like Freedom House’s annual Freedom in the World Report, the U.S. State Department’s annual report on human rights, and the 2014 United Nations Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in the DPRK.

*Random sampling would be extremely difficult to organize, as population lists and demographic data are not publicly available and participating in surveys that are not authorized by the government is extremely dangerous. As polling expert Karl Friedhoff noted in a commentary on surveys in North Korea, “Working in circumstances as difficult as these requires that normal methodological rigor be put aside. The very serious risks assumed by everyone involved demand it.” In another article on survey work inside the DPRK, public opinion researcher Myong-Hyun Go stated that there can be important advantages to conducting survey work among acquaintances in North Korea, as the participants can trust that interviewers will protect their confidentiality, which increases the likelihood that they will provide truthful responses.

4

WHAT WE FOUND

The questionnaire, our analysis of Pyongyang’s behavior during the pandemic, and the Kim Jong Un regime’s dismal track record on human rights revealed five observations on the COVID-19 experiences of the 100 North Korean responses related to the timing and severity of outbreaks; levels of medical support for everyday citizens; second-order effects of lockdown policies; access to information; and public responses to the regime’s handling of the pandemic. Collectively, these observations provide a window into the neglect and abuses of the government, as well as the depth and nature of hardships endured by our interviewees:

- The DPRK government purposefully misinformed these citizens and the global community about the extent of the pandemic inside North Korea. Deaths and suffering due to suspected COVID-19 cases were widespread in North Korea starting in 2020, despite government public proclamations to the World Health Organization (WHO) of “zero cases,” and well before the first official announcement of an outbreak in May 2022. Based on the number of people who were given access to testing and vaccines after May 2022, many lives could have been saved if the government had been truthful about the extent of the pandemic to outside health authorities and accepted international help from the onset of the crisis in 2020.

- Prior to May 2022, citizens had virtually no access to vaccines, no antiviral medications, and minimal supply of personal protective equipment. It’s probable that the national government dealt with the pandemic crisis by essentially shirking any responsibility and allowing the populace to fend for themselves.

- It’s likely that the regime’s strict lockdown policies extended well beyond the survey population and deepened the suffering of ordinary North Koreans by exacerbating preexisting food and medicine shortages and providing new justifications for surveillance and extreme punishments.

- Individuals and agencies at the local level hesitated to provide truthful reports about suspected cases because of fear of punishment for not echoing the government’s disinformation about “zero cases.” It’s probable that the resulting void of accurate information about COVID-19 among the North Korean public exacerbated suffering through the further spread of the pandemic.

- Resentment and cynicism toward the government, as well as the use of bribery to undermine quarantine rules, were widespread, according to the 100 respondents, suggesting that the pandemic generated new sources of vulnerability for the regime even as it used antivirus measures to tighten social control.

Regarding the last observation, the interviews indicated that the pandemic was a period of intense regime surveillance, new restrictions on freedom of movement, and punishments for minor infractions, but it was also a time when ordinary North Koreans witnessed, firsthand, the ineffectiveness of government policies and privately vented frustrations and sought ways to circumvent new rules. Considering the level of punishment individuals face for criticizing the regime in North Korea (imprisonment or death), the frankness of responses to the questionnaires we recorded was notable. And while bribery is not a new practice in North Korea, pandemic quarantine rules provided new opportunities for this segment of the informal economy to expand. Such private, isolated expressions of regime resentment and practices to undermine regime authority could snowball into more visible and widespread forms of rebellion on short notice. Governments that would be directly affected by a DPRK regime collapse should incorporate “hardened shell, weakened underbelly” scenarios into their analyses and preparations.

The following sections detail these observations and discuss their implications for policy and future research focused on North Korea.

a. OBSERVATION ONE

The DPRK government purposefully misinformed its citizens and the global community about the extent of the pandemic inside North Korea.

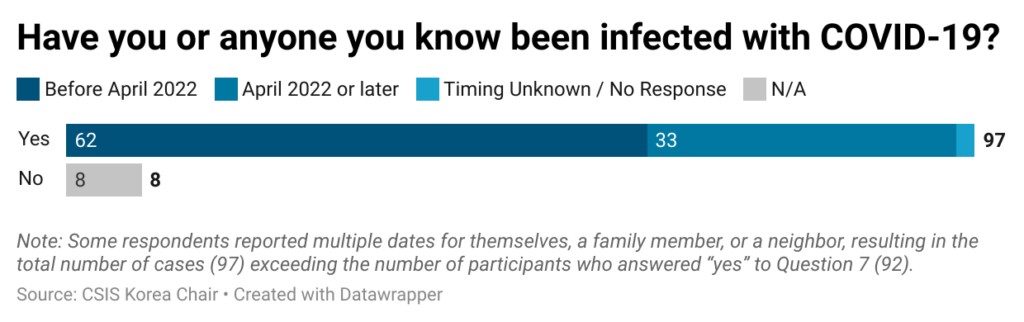

Despite the DPRK’s regular updates to the World Health Organization (WHO) on COVID-19 reporting “zero cases” until April 2022, interviewees report that COVID-19 infections were rampant in the country starting in 2020.

Figure 7

Specifically, when asked whether they or anyone they know has been infected with the COVID-19 virus (Question 7), 92 of 100 respondents answered “yes.” Among these affirmative responses, only 33 cases were specified as occurring in April 2022 or later, while 62 cases were reported to have occurred between May 2020 and March 2022 (Question 7b). Some respondents reported multiple dates for themselves, a family member, or a neighbor, resulting in the total number of cases exceeding the number of participants who answered “yes” to Question 7. Survey respondents reported being diagnosed or placed under quarantine in hospitals, clinics, or military clinics, as captured in survey Question 7f.

A similar pattern was observed in Pyongyang, where more respondents (6 of 14) identified cases occurring before April 2022 than after (2 of 14); the remaining respondents did not specify exact timing. Given what we know about how COVID-19 spread, the fact that 92 of the 100 people interviewed knew someone with COVID-19 suggests that the virus may have been widespread in the country long before the government’s first publicly reported case in April 2022.

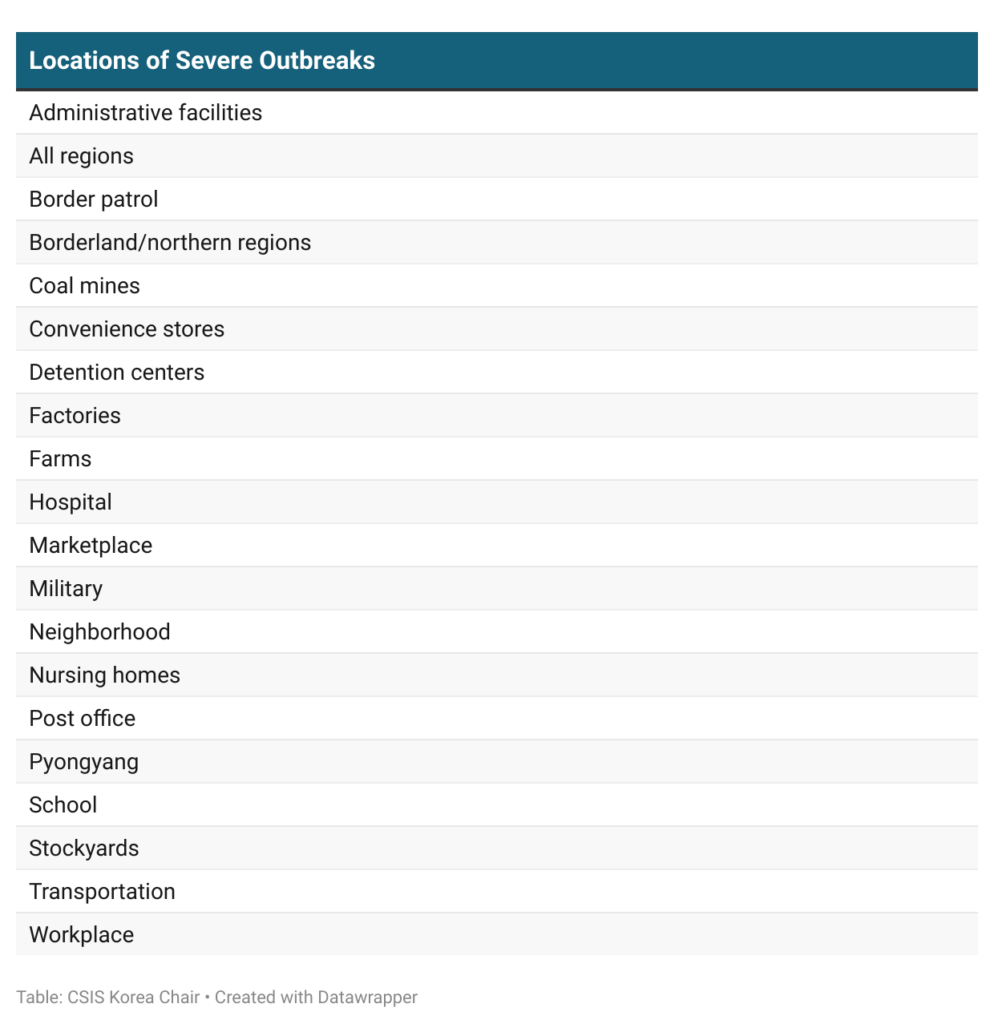

The citizens surveyed were aware of severe community and nationwide outbreaks occurring well before April 2022 despite government disinformation downplaying the outbreak. Asked “When did you feel that the COVID-19 virus situation was at its worst in North Korea?” (Question 8), more than double the number of respondents judged the situation at its worst during the years 2020 and 2021 (50%) than during 2022 (24%). Five respondents listed two or three peak phases of the virus, including one soldier who identified three outbreaks in 2020, 2021, and 2022 and noted, “There was an increasing number of patients with body aches and fever who were unable to work, and military doctors (medical officers) said that they could not prescribe medicine despite it likely being COVID-19. The disease suddenly spread.” One worker from a detention center also identified three outbreaks in 2020, 2021, and 2022, stating that “prison guards, foot soldiers, and employees were not allowed to leave work for seven to 10 days” during an April-August 2021 outbreak.

Those interviewed suggested the scope of the outbreaks was wide, encompassing many public locations. When asked where the situation was the worst, common responses included specific locations such as schools (13 of 100), neighborhoods (11 of 100), factories (9 of 100), and military facilities (9 of 100). One notable response from a soldier stated that “half (360-400 people) of four companies in the mobile communications battalion” were affected by an outbreak in November 2021. One respondent who identified an October 2020 outbreak in a food factory said, “More than 10 people missed work because they were sick, and some people collapsed while working in the field and got taken to a hospital.”

Table 1

In the absence of a testing regime or other official metrics, most of the North Koreans who were interviewed could only deduce the seriousness and location of the outbreaks by the prevalence of severe illness or deaths (Question 8).

In the absence of COVID-19 tests, anyone with cold or fever symptoms was assumed to have contracted the virus. As one respondent whose family member became ill in November 2020 noted, “At the hospital, if a person has a fever and cold symptoms, it was suspected to be coronavirus.” Similarly, one respondent discussing a December 2021 case claimed, “They said it was COVID if you have a fever and cough.” Another, describing a case from May 2022, claimed, “City hospital decided that it could be a cold (flu) and that I was a confirmed COVID case.”

Twenty-five of 100 respondents referred to deaths as their main indicator for outbreaks. As one participant, who identified 2020-2022 as the worst phase of the pandemic, said, “Fevers were happening everywhere, and many people were dying within a few days.” A woman working in the student/education sector highlighted that conditions were particularly bad in winter 2020 “with a lot of cases across the country, students in schools, people in nursing homes.” Within nursing homes, she said, “there were so many deaths that there weren’t enough coffins, so I thought it was serious.”

About another quarter of participants (23 of 100) indicated that they knew COVID-19 conditions were severe because of government actions, such as introducing strict quarantine rules or making public announcements. For instance, a woman who identified factories in October 2020 as a site of a severe outbreak claimed, “My daughter had to listen to explanations about COVID in her factory every morning, even outside of morning propaganda reading time.”

b. OBSERVATION TWO

Government negligence forced ordinary North Koreans to endure the pandemic on their own, with minimal access to professional health care, medicine, or COVID-19 vaccines.

Interviewees reported that the North Korean government’s support for its ordinary, nonelite citizens was virtually nonexistent, particularly during the first two years of the pandemic. This truth flies in the face of statements by the leadership that the DPRK’s “advantageous Korean-style socialist system” was a critical factor enabling the country to manage COVID-19. As one participant said, “The country says it provides free medical care, but there is no such thing as free, and when hardship strikes the country, people don’t look to anyone.” Another noted, “There’s nothing good for us if there’s no proclamation or declaration from the government. If we get sick, money is everything. They don’t give us anything.”

COVID-19 Testing

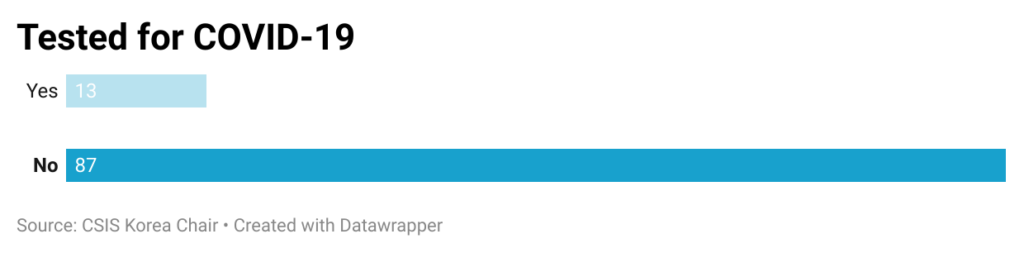

Almost 90 of 100 respondents had no access to COVID-19 testing during the pandemic. Of the small minority that did, most were not able to access testing during the first two years of the lockdown.

Figure 8

When asked whether they were ever tested for COVID-19 (Question 15), 87 of the 100 respondents said no. Of those who said yes, two indicated that they had privileged access through relatives, and three said they were tested through the military.

Had the government been proactive in seeking international help for COVID-19, it could have limited the harm to its citizens. Our survey found that the majority of respondents who reported access to testing did so after 2022 (69% – 9 of 13 participants who had access to testing), likely after offers of testing and medical supplies from China increased following the first official announcement of an outbreak in May 2022. The remaining 31% of respondents (4 of 13 participants who had access to testing) did not specify a date, so it is unclear exactly when their tests occurred, though none explicitly reported access prior to 2022.

COVID-19 Vaccines

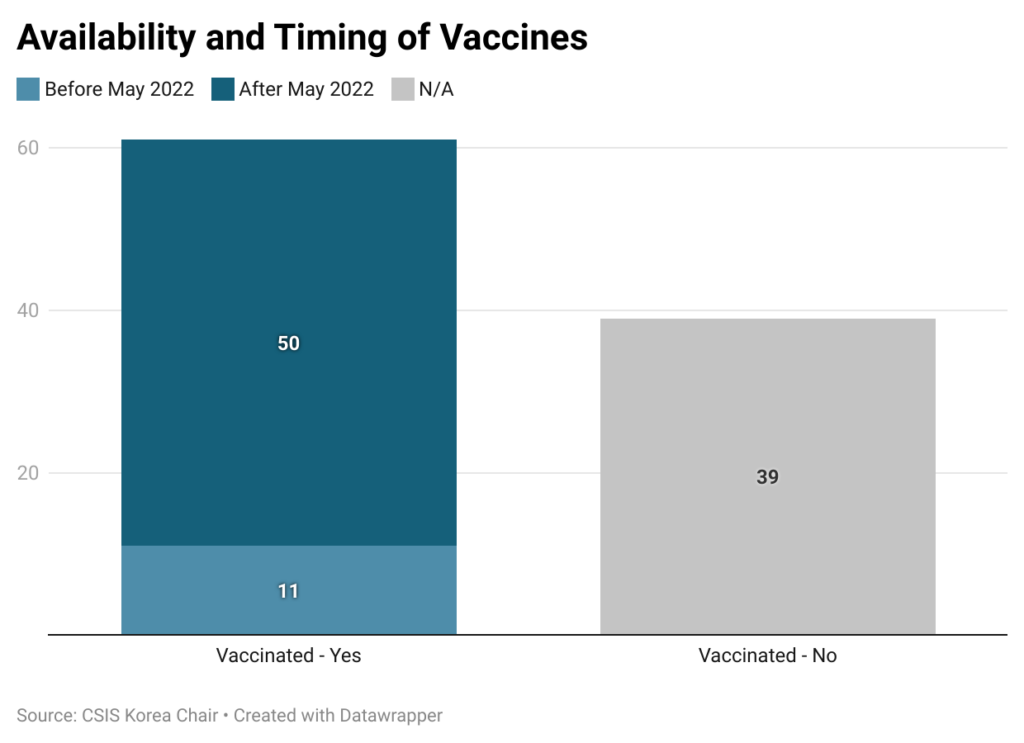

The ordinary public (defined as nonelites and nonmilitary) had limited access to COVID-19 vaccines, with almost 40 of 100 respondents reporting not having received a vaccine during the pandemic. The military was an exception and appears to have undergone a mandatory three-shot vaccination program with China-provided product.

Of the ordinary members of the public who received vaccines, the majority of vaccinations for the people we interviewed happened after May 2022, though the country reportedly began receiving assistance from China months earlier. This again indicates that the government could have averted many deaths if it had reported outbreaks to, and sought help from, international health authorities during the first two years of the pandemic. The government declined international offers of the AstraZeneca and Sinovac vaccines in 2021.

Figure 9

Eighty-two percent of those North Koreans who indicated that they had been vaccinated for COVID-19 received their first shot after May 2022 (Question 15[2]). By comparison, South Korean citizens started receiving their first jabs in February 2021; in the United States, vaccine programs started in December 2020. Fifty-seven percent of respondents who were vaccinated (35 out of 61) referred to receiving their shots “as a group,” either by neighborhood watch units, in hospitals, at schools, or in the workplace. Soldiers indicated that they received three vaccines in 2022, most likely in May, July, and September, and some indicated that the shots were mandatory. Soldiers said the vaccines were from China.

These results track with external media accounts suggesting that the DPRK accepted and started administering vaccines from China from June 2022. The timing of “group jabs,” mostly occurring in late 2022 or early 2023, further coincides with Kim Jong Un’s September 2022 announcement of a vaccination campaign to begin at an unspecified time in the fall.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

The government supply of masks was insufficient, with most interviewees reporting buying, making, and reusing them. Children were especially disadvantaged.

Only eight of our 100 respondents said the government provided masks as an infection control measure. However, citizens understood the value of PPE because when asked, “Did you wear a mask while the coronavirus was spreading?” (Question 14), all of the participants replied yes, but most either purchased the masks in the market (28), made the masks themselves (17), or both bought and made masks (22) (Question 14b). Multiple responses were allowed.

Only one of 100 responses indicated that “children were prioritized for masks” to Question 13, part 5: “Did schools, neighborhood watch units, or the government take measures related to children?” One respondent noted: “Adults were given one dose [mask] during the entire COVID period, but children had to make their own because the size was small.”

A notable number of respondents (21 of 100) indicated that they washed their masks frequently for reuse, which, unbeknownst to them, did little to prevent infection. As one participant noted, “Washing and using disposable masks from the market lasted up to a week. More people washed and used homemade masks.”

Interviewees reported that the government generally neglected providing support to the needy, while ensuring extra support to elite groups during the pandemic.

Those surveyed perceived that elite groups – such as those associated with the party, government, military, or others that the regime designated as “special subjects” – were recipients of extra support. Participants indicated that small amounts of food and medical supplies were provided to households designated as starving or poor. However, over half (54 of 100) responded that no action was taken to help vulnerable populations.

The only device to which North Korean respondents reported having access to combat the pandemic was a thermometer, which they often had to acquire themselves by purchasing, borrowing from a neighbor, or pleading with provincial officials. When asked “During the COVID outbreak in 2022, were you or people you know able to get thermometers?” (Question 18), 87 of 100 respondents said they were able to, but respondents noted that domestically produced thermometers did not work and that there were price spikes for imported thermometers from China – in some cases as high as a fivefold increase.

With a limited testing regimen and limited vaccines, interviewees reported relying on self-isolation and home remedies – everything from saltwater rinses to making garlic clove necklaces – to counter the virus.

Ninety-five of our 100 respondents said that they isolated, mostly at home, for anywhere from three days to three months (Question 16a, Question 16b, Question 16c). Only 11 said that they were able to receive regular health checkups during the COVID-19 lockdown(s) (Question 19).

Participants shared a number of home self-treatments and folk remedies (Question 15):

- “Opium shots for immunity”

- Saltwater treatments: gargle rinsing, toothbrushing, bathing, inhaling burning wormwood

- Cold towel compresses

- Sauna/sweating

- Root tea, juniper seed tea, “10 ginko nuts for tea”

- Garlic clove necklaces

- Gochujang soup

- Mixing various combinations of garlic, scallions, miso, and chili powder or red pepper flakes with

water

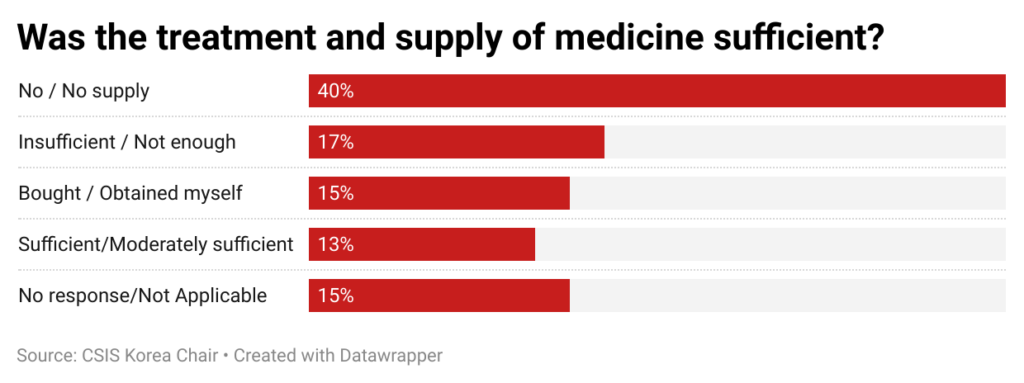

The lockdown exacerbated already depleted stocks of medicines in North Korea, making them scarce, expensive, and sometimes only available through black market sellers. Many respondents reported avoiding asking health authorities for cold medicines because the request could trigger quarantine. For those who could afford it, they resorted to black market sellers (at inflated prices). For those who couldn’t, they simply did without any pharmaceutical interventions and coped with only home remedies.

Figure 10

Fifty-seven of our 100 respondents said that they had no medicine or insufficient access, likely due to shortages in government-provided supplies, while only 13 stated that they had sufficient or moderately sufficient supplies (Question 16d). Fifteen said they purchased medicine on their own.

When respondents suspected or confirmed a COVID-19 infection through testing, they generally reported that medicines (such as cold and fever medications, anti-inflammatories, upset stomach medicine, etc.) were only available for people to purchase themselves in the markets or pharmacies, obtain from acquaintances, or rely on existing home supply (about 70 of 100) (Question 15, part 5). A number of respondents (19 of 100) indicated that they relied on black market sellers or vendors for medicine. As a woman who works in the party/government agency noted, “Medicine, I bought it secretly from someone at their home. The government cracked down on such home pharmacies, so they only sold to people they knew.”

Many also highlighted price gouging, which made the situation more challenging. As one respondent noted, “I should’ve purchased it at the market, but I couldn’t afford it.” Another said, “During the pandemic, medicines dried up, and the price increased a lot, so it was difficult to buy them.” Imported medicines were reportedly hardest to find (Question 17). One participant said, “… imports were not coming in due to border closures, so the prices were high, and I could not fulfill my needs. Another participant said, “No basic medicines such as antipyretic, anti-inflammatory, general cold medicine, diarrhea medicine, etc. were available. No Chinese medicines were available, or they were priced eight to 10 times higher.”

A Climate of Desperation

The government’s neglect in providing any pandemic support or accurate information to its citizens engendered a climate of desperation in which citizens misused medicine or were victimized by fraudulent salesmen. This misuse of medicine in several cases caused further deaths and suffering.

A substantial number of respondents (20) said they were aware of damage, and even death, caused by medicines that were either folk remedies, fake, or not taken properly (Question 15[6]). For instance, one respondent noted, “There were a lot of fake medicines, and people died because they couldn’t use real medicine.” Another said, “There are a few people who died because they should have taken medicine that suits their illness, but if they hear a medicine is good, they start taking it without looking into what it really is.”

Fake traditional Chinese medicines were a concern for one respondent, who said, “The mother of a farmer’s wife at the funeral took fever medicine, sore throat medicine, and anti-inflammatory medicine from the market, but died of side effects from fake drugs (many of the traditional Chinese drugs were counterfeit).” Two respondents referred to the misuse of penicillin, such as one who noted, “Someone I know in Ganggu died after receiving the wrong penicillin.” In two cases, the use of opium was mentioned, such as the participant who said, “Unable to wake up after receiving opiates.” Three cases involved using the wrong dosage for children, including a baby who died because his mom “gave him a full pill instead of a quarter pill per day.”

c. OBSERVATION THREE

Suffering among North Korean respondents in our survey was exacerbated by the government’s strict quarantine policies, a worsening food crisis, and extreme punishments for breaking antivirus rules.

The government relied almost entirely on nonpharmaceutical interventions to combat the pandemic. This entailed severely restricting citizens’ movements around the country, a crackdown on all market activity (both official and black market), school closures, and the blocking of all trade and travel with China. These measures exacerbated economic downturns and food and medicine shortages. By comparison, in the mid-1990s when the public distribution (ration) system broke down, the government allowed the people to fend for themselves through the creation of informal markets. But no such compensation mechanism existed during the pandemic when the public health system failed to protect the people. According to survey respondents, the only mechanisms created to fill the medical vacuum were home remedies and fraudulent pharmaceuticals which, as noted above, resulted in fatalities.

Responses to the survey indicate that the external border lockdown starting in January 2020, internal quarantine measures, and a series of new stringent anti-epidemic laws worsened already-dismal economic, food, and human rights conditions in the country. Seventy-seven of our 100 respondents said it was “impossible” to travel to other areas in search of food during the pandemic (Question 23). Controls appeared to be strictest in Pyongyang, South Hamgyong, and Jagang. Members of the military were granted special permission to move around, noting “ordinary citizens not allowed to move around; military messengers with approved travel orders (etc.) could.”

Eighty-one of 100 respondents indicated that they experienced acute food shortages during the COVID-19 lockdowns (Question 22). One participant noted, “Food was too expensive, and I didn’t have enough money to make ends meet.” Another respondent simply stated, “I thought I was going to die.” Soldiers who responded weren’t spared from the food crisis; six out of the seven soldiers in the survey sample indicated that they experienced food shortages: “Everyone was quarantined in their houses (even if it was just one person), and the quarantine periods were very long, so you had to have emergency food at home. If you didn’t, it was really tough.”

The market was the only place North Koreans could acquire needed items, but the lockdown created shortages of goods, and scarcity led to price surges that made the goods unaffordable. Ninety-seven of 100 respondents identified scarcity and price spikes for food, imported medicine, and other necessities (Question 17). One respondent pointed out an underlying irony of the strict quarantine measures, noting, “They say that people are quarantined and controlled to ensure that there is no risk to people’s lives and safety, but because of this, their lives and safety are more at risk.”

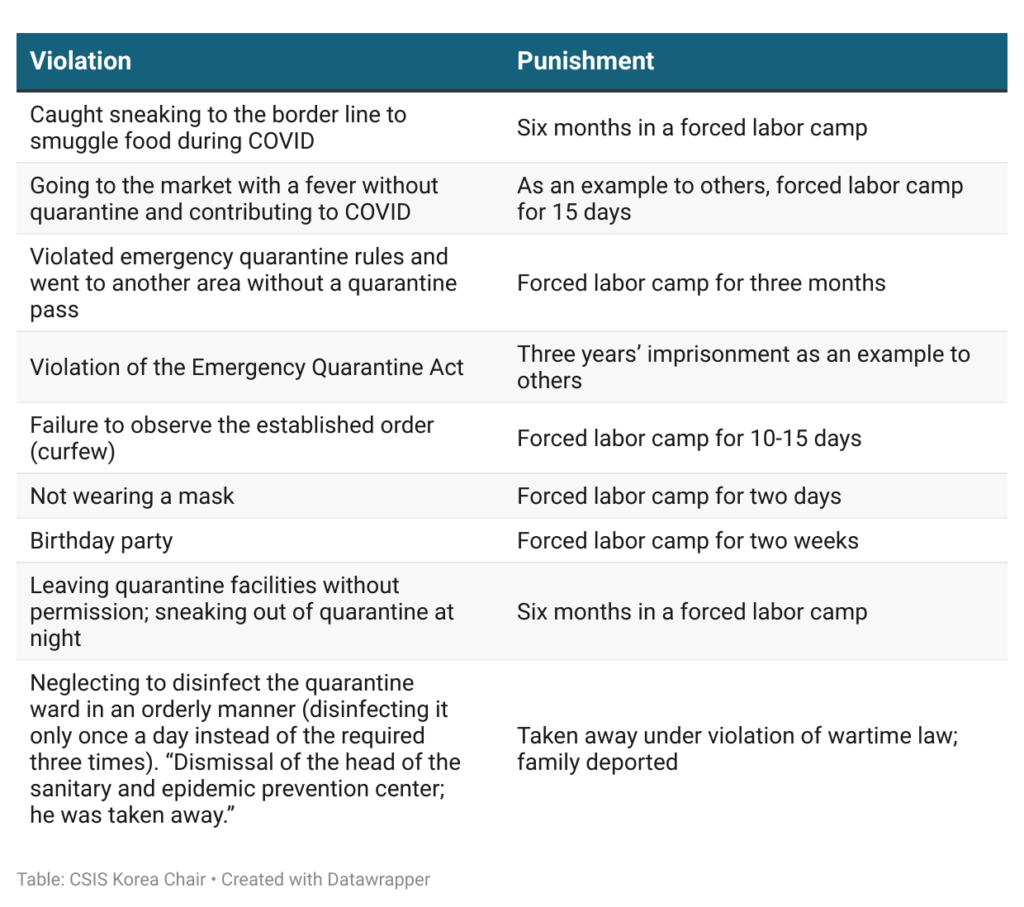

Table 2

Those we surveyed indicated that those who were caught breaking lockdown rules were severely punished. Eighty-five of 100 survey participants indicated that rule breakers were punished during the “emergency antiepidemic period,” (2020-2023; Question 11) most often by sending them to forced labor camps (48 responses mentioned forced labor camp or imprisonment). Examples of a range of violations and corresponding punishments are provided in Table 2.

Military service members seemed to be spared from the harshest punishments but still received sanctions. For instance, one soldier noted, “A midlevel soldier in the battalion sneaked out in the evening because he was hungry and was caught by the owner of a farm with kimchi.” As a result, “The battalion begged for forgiveness at the village party committee and the midlevel soldier was demoted to sergeant.” Another soldier said, “Two of the (military) company’s officers took off their masks because it was hot.” Their punishment was “one month punishment work (cleaning the latrine).”

d. OBSERVATION FOUR

Local health officials misreported COVID-19 deaths and diagnoses to align with government directives that the DPRK had “zero” cases (before 2022). This resulted in a doubling of misinformation whereby the government and citizenry each lied to the other, creating further spread of the pandemic. We believe the responsibility for this disaster lies squarely at the feet of the government because its disinformation, draconian NPIs (lockdowns), resultant food shortages, and lack of PPE provision forced the public ultimately to behave in self-destructive ways in order to survive.

The government compiled statistics on cases within the country but did not disseminate the results broadly or consistently to everyday citizens. Most participants (87 of 100) indicated that government entities – including neighborhood watch units, security officers, quarantine centers, health clinics, and people’s committees – initially recorded data from fever checks and household inspections on severe and fatal cases of COVID-19 (Q12) for reports to central authorities. But little feedback or help came from the government other than lockdowns which exacerbated food shortages. For example, only 41 of 100 participants indicated that they ever received the investigation results of COVID-19 cases reported through official government channels (Question 12c). Official channels included neighborhood watch unit meetings, doctors, epidemic prevention centers, security guards, party officials, state TV broadcasts, or government-sponsored meetings and lectures.

One participant stated: “The results were not well communicated. Don’t know exactly,” while another noted, “[We got information] [t]hrough rumors. They didn’t share investigation results.” Respondents indicated that the frequency of checks decreased over time, including one who said the checks were “initially managed by doctors who did rounds, but not since late 2021.”

Doubling Misinformation

Official government policy before May 2022 stated that the country had “zero” cases. Respondents indicated that local reports of outbreaks were therefore met with censure and even punishments. It’s likely the combination of disinformation and blatant negligence from the government, food shortages, and the desire to avoid draconian lockdowns compelled the citizenry to take harmful actions for themselves. Accounts suggested that doctors, local officials, and ordinary citizens preferred not to record symptomatic cases, either to protect individuals from quarantine or to avoid criticism from the central government.

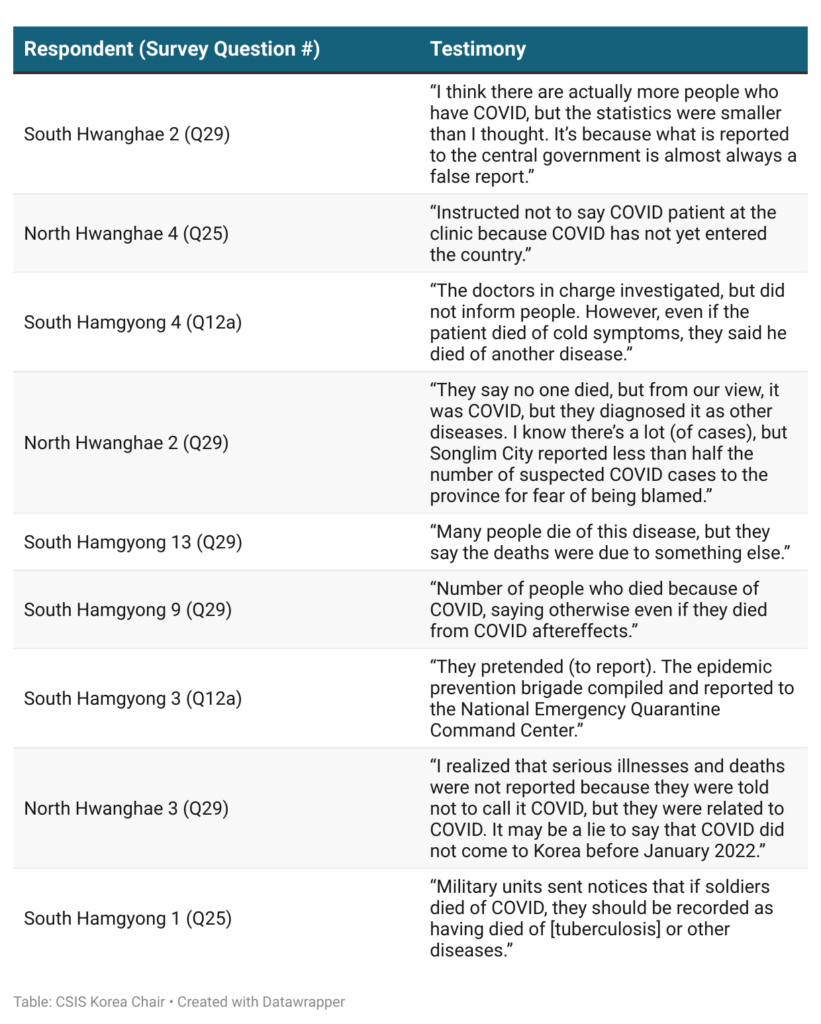

As one participant said, the “clinic doctor told me that I have COVID and that if I say that, I will be taken away.” Another noted, “It is more advantageous to say that people died of other diseases even though they know that they died of COVID because it is obvious that the living people will be quarantined for a long time and suffer more due to the spread of the virus.” Another testified, “I treated myself because I’m afraid they’ll look at me like a criminal if I told them.” Yet another testified, “I realized that serious illnesses and deaths were not reported because they were told not to call it COVID, but they were related to COVID. It may be a lie to say that COVID did not come to Korea before January 2022.” Table 3 contains a sample of responses showing the widespread practice of misreporting COVID-19 cases for fear of lockdown or censure.

Table 3:

North Korean Citizenry Forced to Misreport COVID-19 Cases for Fear of Censure and Lockdown

Under normal circumstances, and in almost every other country in the world, it would have been the responsibility of citizens and health officials to accurately report COVID-19 data, but North Korean citizens could not be blamed for the widespread inaccurate reporting. We know from sources like the Freedom in the World Report that North Koreans have virtually nonexistent civil liberties or political rights and that they lack any mediating institutions independent of the regime. As such, that responsibility sits entirely with the government for creating a poisonous atmosphere of distrust with the public. Rather than being able to look to the government for medical help, citizens experienced a situation in which reporting sickness meant forced individual detention or collective lockdowns, either of which would exacerbate acute food shortages. The only way to survive or avoid punishment was to misreport, which in the end only caused the pandemic to spread further.

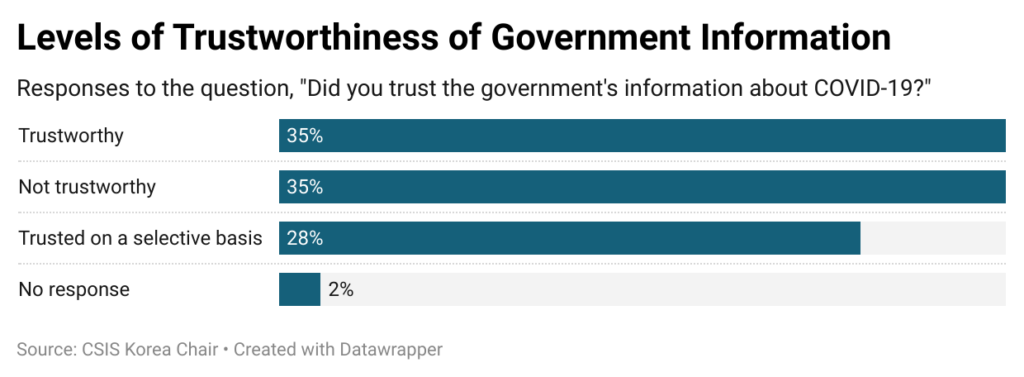

Our survey showed that mistrust of the government was rampant among respondents. Only a minority of respondents (35 of 100) said they trusted information from government-affiliated sources such as Rodong Sinmun (Question 28). Most (73 of 100) said they sought out information through unofficial channels (Question 27).

Figure 11

While many simply responded “believed,” or “disbelieved,” some participants elaborated on their reasons for not trusting the government. For instance, one Kangwon resident noted, “No. The government has never really said anything true.” Some respondents said, “I believed the quarantine instructions, but I didn’t believe the other announcements because they were mostly lies.” Another said, “I believe what I see, and I don’t believe what I don’t see.”

A vast majority of the survey respondents (83 of 100) identified discrepancies between government announcements and their own experiences of the pandemic (Question 29). More than half of the participants (60 of 100) expressed doubts about the DPRK’s official statements regarding having the virus under control during the early years of the pandemic. For instance, one respondent stated, “The government is saying that the world is in chaos due to COVID and that the country is well protected, but, in fact, many people are dying because they have no money to eat and cannot get medicine.” Another noted, “The government was ridiculous when they said that other countries had a lot of deaths from COVID but we had no deaths.” And a third declared, “They say there are no deaths because of good quarantine efforts, but I think there are many deaths.” A soldier was similarly skeptical, noting, “They fooled soldiers for two years in 2020 and 2021, saying that COVID was under control and that they could take cold medicine because it wasn’t COVID. COVID has already spread in our country, and the cold my daughter had was COVID.”

Others scoffed at the regime’s propaganda. As one respondent said, “Other countries have many deaths due to COVID, and the economic situation is bad due to restrictions on entering and leaving the border, but DPRK is touting that there are no deaths due to the government’s measures and thorough countermeasures, but in reality, there are many complaints from households.” Another noted, “The government says they are treating patients with domestic medicine to overcome it, but many people haven’t even tried it because of the shortage of medicine.” A third participant found it hard to believe “That we closed our borders because we prioritized the well-being and health of our people,” noting that “there are many people with severe aftereffects from COVID.”

Disinformation Campaigns

The government disseminated heavy doses of disinformation, including assertions of “zero cases” inside the DPRK due to “successful socialism” and conspiracy theories about U.S. and South Korean germ warfare.

Nearly 70% (69 of 100) of respondents correctly identified China (with some more specifically citing Wuhan) as the site of the first COVID-19 outbreak, and many others understood that the virus had spread to many parts of the world (Question 26). Yet the regime used this information to propagandize the success of its own pandemic efforts, in contrast with other countries. A Pyongyang resident noted, “The COVID situation was constantly and continuously broadcast on TV and in the newspapers, but the most common thing I heard was that other countries are suffering a lot, but the DPRK is overcoming the crisis well due to Kim Jong Un’s wise leadership.” Another respondent said, “At every meeting and lecture, they touted the superiority of socialism by reporting on the situation and deaths of COVID patients in countries around the world.”

More than one-third of respondents (35 of 100) believed that South Korea sent the virus into the DPRK through various means, including balloons, imported rice, leaflets, and “unauthorized river crossers.” *As one participant said, “They say it all came from China, but South Korea sent it in, because South Korea has a bad relationship with our country.” Another noted, “Heard that South Korea shot at us with germs (weapons? balloons? guns?).” These accounts echo the August 2022 claims of Kim Yo Jong, Kim Jong Un’s sister, that South Korea’s anti-Pyongyang leaflets were to blame for spreading COVID-19 in the DPRK.*

For some of the most elaborate conspiratorial accounts, the source of information was unclear. For instance, one respondent noted, “I heard that the U.S. will make COVID viruses to spread in China and to bully China. And that the medicine is made in the U.S., so they are making money.” Another said, “It’s an American operation. No, there is nothing the U.S. can’t do, they told us.” And a soldier noted, “I heard that China had COVID first, but it was a U.S. CIA-run lab that ran germ tests and that it was a U.S. plot to ruin China (on purpose) and kill the 30 million people of the DPRK by sending it across the border.”

e. OBSERVATION FIVE

Many respondents expressed resentment toward the government’s handling of the pandemic. This precipitated a willingness to circumvent quarantine rules through bribery, revealing new areas of vulnerability for the regime.

A collection of anecdotal responses to various survey questions revealed frustrations with several aspects of the government’s handling of the pandemic. Many respondents compared their situations unfavorably to the circumstances they heard about in other countries. For instance, one respondent noted, “I heard that other countries have all their COVID shots, and if you get sick, they’ll cover your medication. In my country, if you have a fever, all you can do is quarantine or go into lockdown.” Another said, “We’re the only country that still has its borders closed following COVID. I heard that (people in other countries) began living their lives as normal soon after COVID began. I heard that people got free

medicine if they got COVID. Our country doesn’t care if you live or die.” Similarly, a third participant noted, “People in other countries can travel the world, but we still can’t even walk on certain roads.” And a fourth said, “I heard that the DPRK doesn’t test for COVID, but other countries do. There is a lockdown here, but I heard this isn’t the case in other countries.”

Grassroots Anger and Frustration at Government Elites

Respondents expressed deep frustration and anger with preferential treatment for North Korean government elites, particularly related to accessing medicine and COVID-19 vaccines while the general public suffered. As one participant said, “Many people died crossing the border during COVID. The dead bodies were left there to become fish food. They burned a South Korean person who crossed the border from South Korea due to the virus. The central party cadres are using COVID medicines but not taking care of the people.” Another noted, “In my country, only the central party cadres are considered

people, and the real people are treated worse than pigs…. COVID is like a cold if you get a vaccination.” A third said, “The Central Committee cadres used illicit drugs during COVID, but they only used good-quality stuff. It was better than the stuff circulating in ordinary society.” And a fourth said, “It was rumored that everyone would be jabbed when the vaccine came in from China, but only the top officials got it.”

Three further responses along similar lines: “Central Committee cadres were jabbed with (vaccines) made in the U.S. during COVID”; “the central party cadres were jabbed several times since the beginning of the lockdown, and the people were jabbed once with something they don’t have any idea about where it’s from”; and “Central Committee officials jabbed with U.S.-made COVID shots. People are treated like animals, viruses similar to COVID will continue to emerge in the future, and COVID is now treated like a cold. North Korea refused to take vaccines offered by other countries.”

The largest category of frustrations focused on the general ineffectiveness of government’s COVID-19- related decisions, such as refusing vaccines or other forms of aid from other countries and prolonging the border lockdown as the world began to reopen. One respondent said, “Only my country has closed borders and doesn’t allow travel between regions, and I heard that other countries offered vaccines, but we refused. They don’t care whether the people live or die because they have good quality medicine and got jabs.” Another noted, “The U.N. said they were going to give our country medicine and rice, but the Supreme Leader stopped them. Even if these things were imported, they wouldn’t give it to us for free, so why can’t we buy it and consume it?” A third said, “They claim to have an emergency quarantine campaign in place, but they only conduct crackdowns and don’t let us make a living.” And a fourth participant noted, “Nothing was right. I’m nervous about the number of COVID patients, the number of deaths, the number of severely ill patients, and why they still don’t open the border when other countries are fine.”

The government’s negligence during the pandemic pierced the propagated myth in North Korea that the regime’s leadership and actions are unquestionable. Some responses directly challenged the notion that the regime cares about its people. As one Pyongyang resident said, “When I see saw [sic] the Supreme Leader touting his leadership, love of the people, and the superiority of the Republic while announcing that there are almost no deaths in the Republic, even though so many people have died during COVID, I think of the people who have died without being able to get the medicine they needed.” And another respondent noted, “Even when COVID was said to be over, many people were still sick. The number of COVID cases, the number of deaths, they say that everything (they do) is for the people.”

Some respondents questioned the regime’s prizing nuclear weaponization over the pandemic. For instance, one respondent said, “The DPRK government developed nuclear weapons during COVID, but it didn’t care about feeding its people.” Another noted, “Other countries have all the COVID shots and give free medicine if you get COVID, but we don’t have medicine. Border is closed because of COVID, so it’s not likely to open. I heard many people who made a lot of money while working in COVID-19 related agencies. More people are starving than sick, and the DPRK blows money on missile launches.”

It’s fair to say the pandemic gave the North Korean government unprecedented power to control and lock down its population even by its own standards. But this period of draconian control seems to have created antibodies among a society that revealed cracks in the façade of the regime. It’s likely that what motivated this societal resistance was, at its core, a basic will to survive.

Citizens’ resistance came in the form of disbelief and criticism of the regime’s directives and propaganda as described above, but it was also evident in behavior such as widespread bribery to flout quarantine restrictions during the pandemic. Bribery is arguably one of the most threatening activities to the regime because it compels collusion between the citizens and the government officials against the state.

A majority of respondents (62 of 100) said they had given bribes to circumvent quarantine restrictions (Question 24). Many citizens engaged in bribery more than once or twice to as many as 11 times. Amounts varied, from 50,000 up to 500,000 North Korean won. Boxes of cigarettes were another common form of payment. Moreover, the targets of the bribes were almost all conceivable levels of government, party, and the military, including police officers, “officials in charge of special documents,” epidemic prevention officers or quarantine officers, police or security officers, and doctors in a clinic. Answers to the question “to whom” the bribe was paid included local officials of various types. All but one of the seven soldiers in the survey were willing to engage in offering and accepting bribes during the pandemic.

Limited resources and time prevented us from deeper questioning of respondents on resistance to the government. While the survey documents grassroots anger and frustration with the government and episodic efforts to flout government restrictions, we are unable to determine based on this evidence whether the pandemic created conditions for regime instability.

*A subset of respondents rejected governmentfueled conspiracies identifying South Korea as the source of the virus. For instance, one respondent said, “I’m convinced that it’s wrong that COVID came in from South Korea and that it spread the virus (here); what’s the point of sending it from South Korea through leaflets or whatever?” Another said, “The reason why the government didn’t make it clear that COVID started in China – for fear of losing goodwill with China. Pushing it off on South Korea muddies the waters.” Notably, respondents from Kangwon, which borders South Korea, pushed back against Kim Yo Jong’s claim that leaflets from the South spread the virus, noting “Kangwon Province has nothing to do with COVID”; “Comrade Kim Yeo-jung’s statement about COVID outbreak in Kangwon Province is not true”; and “I don’t believe China would’ve allowed South Korea to come in and spread the disease.”

5

POLICY AND RESEARCH IMPLICATIONS

For governments and international organizations seeking to improve the welfare of North Koreans, these observations can guide positions, initiatives, and policies on a range of issues. Many of these recommendations involve enhancing or continuing existing initiatives:

Do not accept official DPRK statements or data at face value. A good rule of thumb is do not trust, and verify.

- Gathering as much information as possible regarding conditions within the country from a broad range of sources – rather than relying primarily on DPRK state media reporting and official announcements – continues to be the best strategy for seeking truth on the ground in North Korea.

- International organizations like the WHO should attach caveats to reports and statements that include data supplied by the North Korean government, indicating their degree of confidence in and ability to independently verify the information.

Even if the North Korean government is likely to reject it, continue to offer humanitarian aid when needed. Aid offers should be conditioned on North Korea’s acceptance of international access and monitoring standards and delinked from progress on security issues like denuclearization. Survey responses indicated dire shortages of medical supplies and food during the pandemic, as well as an awareness, among some participants, that their government rejected offers of much-needed humanitarian assistance from the U.N. and countries like the United States and South Korea.

- At worst, the aid will be rejected, but at least some North Koreans who hear about such offers will question how “hostile” these donor countries really are.

- At best, the aid – along with access and monitoring conditions – will be accepted, leading to improved conditions for North Koreans and enhanced reach for humanitarian organizations. While the risk remains that aid could be diverted to benefit only the regime elites, sustained efforts to enforce monitoring standards and to work through trusted humanitarian institutions and actors on the ground will be critical to mitigating this risk and ensuring that aid reaches the most vulnerable populations.

Devise and support legislative and nongovernmental organization initiatives to increase North Koreans’ access to accurate outside information. Responses indicate that many North Koreans are receiving some accurate information, along with significant amounts of misinformation, about the outside world through a mix of official and unofficial channels. Efforts to identify, tap, and expand unofficial channels, while minimizing the risks of punishment or imprisonment for recipients, would help to replace conspiracies (like those about the United States and South Korea) with facts and enhance the ability of North Koreans to evaluate their own conditions relative to the rest of the world.

For those in the United States and allied governments working to identify and prepare for potential DPRK regime collapse scenarios, keep in mind that periods of increased authoritarian control can simultaneously generate new, less visible sources of regime vulnerability. Survey responses revealed that the pandemic brought both new forms of repression and surveillance, as well as new opportunities for North Korean citizens to see their government’s ineptitude in action. In turn, ordinary North Koreans found new ways to challenge and circumvent the system, including through bribery.

- Small-scale antiregime expressions and practices could swell quickly into broader forms of rebellion.

- Government analyses of DPRK regime collapse contingencies should add “hardened shell, weakened underbelly” scenarios into their studies.

Continue to systematically document evidence of human rights abuses to support possible future prosecutions of North Korean leaders. Survey responses provided ample new evidence of human rights violations suffered by North Koreans, including in the areas of rights to freedom of movement and freedom from cruel, inhumane, or degrading treatment or punishment.

- This information should be provided to organizations that are creating evidence repositories that could be used in criminal accountability processes someday, including the U.N.’s Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).

The interview results also point to areas of fruitful future research on North Korea:

- On global health, the findings can help to inform analyses of likely DPRK strategies in future pandemics: Will North Korea employ a similar total lockdown approach or alter its course due to the ineffectiveness of many of its COVID-19 policies, as indicated in the accounts of many survey participants?

- In the area of North Korea’s informal market economy, the survey provides information on the role of black market sellers (also referred to as “private sellers,” “private vendors,” and “dealers”) when more regular market activity has been shut down. Future studies could explore the degree to which these private activities continue or decrease as the country reopens.

- Regarding the North Korean military, future research could explore the degree to which the aspects of the preferential treatment of the military broke down during the pandemic, as soldiers who participated in the survey shared stories of hardship due to food shortages that echoed the experiences of civilians. Studies could also look into whether corruption within the military and other security establishments increased during the pandemic, insofar as the quarantine system offered new opportunities for bribery.

- On North Korean human rights, future studies could track the degree to which new forms and levels of surveillance and repression that the regime introduced during the pandemic are rolled back or maintained as the country reopens.

- Regarding DPRK internal stability, future research could explore whether expressions of resentment toward the regime decrease as the country reopens and more normal economic and social activity resumes or remains the same. Comparisons of expressions of resentment between specific sectors or regions would also be interesting to track.

- The DPRK’s ability to weather the extreme isolation during the pandemic lockdown raises serious questions about the effectiveness of international sanctions in fomenting a change in regime behavior or even in its stability. While not writing off the need for sanctions, the COVID-19 experience suggests the need for discriminating study of which sanctions under what conditions might prove most effective in achieving policy results.

6

CONCLUSION

This report paints a grim picture of conditions in North Korea during its three-and-a-half-year COVID-19-induced lockdown. Isolation, economic and social challenges, and widespread deaths and severe illness were experienced in many countries around the world during the pandemic. But extreme risks of starvation, multiple rejections of international offers of vaccines, official denials of widespread illness, and forced labor camps were not. As the interview results attest, the policies and brutality of Kim Jong Un’s regime made worse a terrible situation sparked by the onset of COVID-19.

For those who have not come across many firsthand accounts of life in North Korea, the depths of suffering that these findings reveal may come as a shock. However, the community of experts who routinely track developments in the DPRK will be less surprised. Sadly, the results represent more continuity than change in compounding the hardships of everyday life for North Koreans. But that does not detract from their importance and potential impact. The information provided here will hopefully aid efforts to document human rights abuses during the DPRK’s deepest period of isolation, inform present day policy and research, and predict future developments in North Korea.

About the authors

Victor Cha is President of the Geopolitics and Foreign Policy Department and Korea Chair at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS); a Senior Fellow at the George W. Bush Institute; and a Distinguished University Professor at Georgetown University.

Katrin Katz is Adjunct Fellow (Non-resident) with the CSIS Korea Chair; a Professor of Practice in the Department of Political Science and in the Master of Arts in International Administration (MAIA) program at the University of Miami; and Van Fleet Nonresident Senior Fellow at The Korea Society.

Seiyeon Ji is Associate Director and Associate Fellow at the CSIS Korea Chair.

About the CSIS

The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) is a bipartisan, nonprofit policy research organization dedicated to advancing practical ideas to address the world’s greatest challenges. Thomas J. Pritzker was named chairman of the CSIS Board of Trustees in 2015, succeeding former U.S. senator Sam Nunn (D-GA). Founded in 1962, CSIS is led by John J. Hamre, who has served as president and chief executive officer since 2000. CSIS’s purpose is to define the future of national security. We are guided by a distinct set of values—nonpartisanship, independent thought, innovative thinking, crossdisciplinary scholarship, integrity and professionalism, and talent development. CSIS’s values work in concert toward the goal of making real-world impact. CSIS scholars bring their policy expertise, judgment, and robust networks to their research, analysis, and recommendations. We organize conferences, publish, lecture, and make media appearances that aim to increase the knowledge, awareness, and salience of policy issues with relevant stakeholders and the interested public. CSIS has impact when our research helps to inform the decisionmaking of key policymakers and the thinking of key influencers. We work toward a vision of a safer and more prosperous world.

About the George W. Bush Institute

The George W. Bush Institute is a solution-oriented nonpartisan policy organization focused on ensuring opportunity for all, strengthening democracy, and advancing free societies. Housed within the George W. Bush Presidential Center, the Bush Institute is rooted in compassionate conservative values and committed to creating positive, meaningful, and lasting change at home and abroad. We utilize our unique platform and convening power to advance solutions to national and global issues of the day.