Training More Providers Will Strengthen our Health Care System and Economy

America needs far more nurses and other health care professionals. Bold moves to recruit and train the health care talent of the future would be a win-win – addressing critical needs and expanding one of the surest paths to economic opportunity for young Americans.

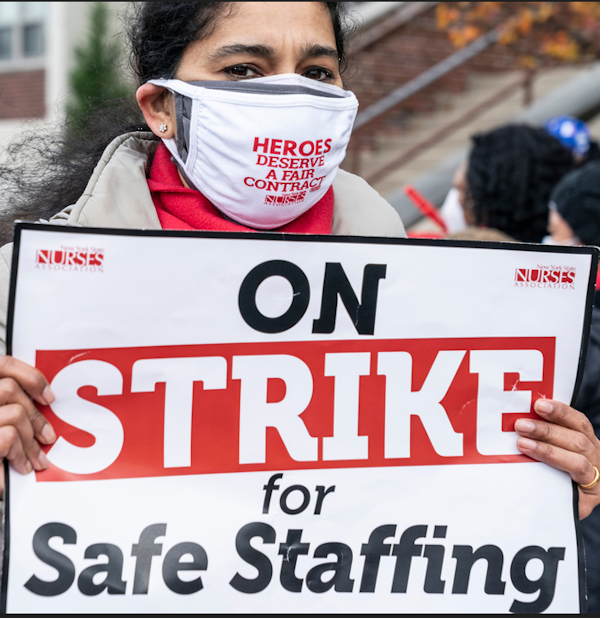

Nurses of Montefiore New Rochelle Hospital on two-day strike after failed contract negotiations in December 2020. (Lev Radin/Shutterstock)

Nurses of Montefiore New Rochelle Hospital on two-day strike after failed contract negotiations in December 2020. (Lev Radin/Shutterstock)

Last year my 24-year-old daughter Annabel decided to go into nursing, after earning a bachelor’s degree in another field. I’m delighted by her choice because nursing fits her so well and because of the good she’ll do. She’s now in a master’s program and well on her way to becoming a nurse, and probably a nurse practitioner after that.

But watching her navigate the complex, inefficient pathways into the profession led us both to a disturbing realization: The system seems designed more to keep people out than to recruit and train the nurses and other health care professionals our nation needs.

Growing shortfalls

America’s health care system today is short at least a million workers, based on unfilled positions. This includes shortfalls of at least 15,000 primary care physicians, 200,000 medical technologists, and 400,000 home health care aides.

But watching her navigate the complex, inefficient pathways into the profession led us both to a disturbing realization: The system seems designed more to keep people out than to recruit and train the nurses and other health care professionals our nation needs.

Consider the case of nursing. One often-cited-measure is the number of nurses per resident 65 or older in the United States. The health care system would need to increase its nursing workforce by more than 300,000 just to return this ratio to the level that prevailed between 2000 and 2010 – a period already marked by pervasive shortages.

Current staffing shortfalls are especially severe in rural and small-town hospitals, many of which have more than 30% of targeted positions unfilled.

Nursing shortages take a serious toll on patients. Hospitals with excessive nurse-to-patient ratios see higher infection rates, readmissions, and post-surgical mortality, according to studies in the New England Journal of Medicine and other respected sources.

America’s nursing shortage, moreover, is growing. The number of active registered nurses (RNs) grew less than the country’s population from 2010 to 2020, then actually fell between 2020 and 2021 under the strain of the COVID crisis. Nursing headcount per 1,000 residents 65 and over has declined to 57 today from 70 in 2010.

Looking ahead, demand for nurses will surge as America’s 65-plus population rises to about 75 million by 2033 from 56 million today and its population of seniors over 80 grows even faster. Meanwhile, one third of today’s RNs, whose average age is 47, will retire. And almost one-in- three active nurses of all ages say they’re considering leaving the profession over the next year, according to a 2022 survey.

Unlike in other fields, technology won’t allow the health care system to reduce nurse-to-patient ratios while maintaining the quality of care, because America’s aging population lives with increasingly complex conditions. Plus, the rapid medical innovation we’re experiencing makes treating patients more labor-intensive than ever.

U.S. Air Force Senior Airman Angela C. Gallagher prepares flu shot. (The National Guard/Filckr)

U.S. Air Force Senior Airman Angela C. Gallagher prepares flu shot. (The National Guard/Filckr)

Here’s the arithmetic: America needs to recruit and train at least 225,000 RNs each year for the next decade just to maintain today’s staffing ratios, and some 250,000 to 300,000 to get back to the healthier levels of two decades ago.

Developing health care talent at the scale America needs calls for a three-pronged strategy.

But the country’s nursing schools produced only 155,000 graduates last year, a level that’s remained essentially flat for a decade. These figures imply that America’s nursing shortage will almost surely exceed 1 million RNs by 2033 on current trends, amounting to a 20%-plus shortfall at the average hospital.

Bright opportunities

Stepping up America’s training of new nurses and other health care professionals offers one of the best available avenues for expanding economic opportunity at large scale, in addition to helping future patients. RNs with a bachelor’s degree typically earn more than $75,000, with significant upside for nurse practitioners (NPs) and other advanced practice nurses. Those with a two-year associate degree earn approximately $60,000 on average, some $20,000 more than the average associate degree holder.

Health care offers particularly attractive opportunities for several specific groups of Americans. One is military veterans. Over 10,000 veterans leave the armed forces each year with military health care training under their belt. About four-of-every-five veterans with this experience don’t have a bachelor’s degree or credential recognized in civilian workplaces and would benefit from more streamlined pathways to become EMTs, med techs, and other vital roles.

Another group is immigrants with degrees or credentials earned in their country of origin. More than 165,000 immigrants who were trained abroad in relevant occupations aren’t working in health care today due to difficulties transferring foreign-earned credentials to the U.S. health care system.

The health care sector also offers tremendous opportunity for underemployed men. More than 11% of prime working age men are disengaged from the labor force. At the same time, men make up only 13% of the RN workforce and just under 30% of med techs, suggesting rich opportunities for putting millions of men back to work in much-needed roles.

Here’s the arithmetic: America needs to recruit and train at least 225,000 RNs each year for the next decade just to maintain today’s staffing ratios, and some 250,000 to 300,000 to get back to the healthier levels of two decades ago.

Attracting the caregivers of the future

Developing health care talent at the scale America needs calls for a three-pronged strategy.

First, Congress and state legislatures should fund significant capacity expansion at schools of nursing and other health care occupations. U.S. nursing schools turn away more than 90,000 qualified applicants each year, according to a report by the American Association of Colleges of Nursing. The chief hurdles to accepting more students are shortages of instructors, facilities, and clinical rotation opportunities. Schools typically can’t expand faculty due to budget constraints and because qualified instructors can earn so much more in patient care.

Congress currently subsidizes nursing education at levels amounting to just under $2,000 per new nurse, or about 3% to 4% of the all-in cost of training RNs. In contrast, Congress invests more than $500,000 in educating each new doctor.

America can afford larger investment in its future nurses, med techs, and other patient-care professionals. We’ve done it before. The Nurse Training Act of 1964 created new funding streams for nursing schools and doubled the number of RNs per capita from 1974 to 1983.

States should also launch new initiatives to expand nursing school slots at public universities, as the Florida Legislature did last year.

Better on-ramps

Second, America needs to build more and better pathways into nursing schools and other training programs – a large undertaking in which all levels of government have roles to play. School districts should introduce more health care-focused “early college” programs into high schools and raise student awareness of opportunities in the sector. Some Texas districts are sending mobile labs to schools in which students can “treat” dummies in a realistic setting.

Congress and state legislatures should fund more grant aid to nursing students, since heavy dependence on debt financing keeps many young people out of health care careers. Local authorities should also step up efforts to connect underemployed people with healthcare retraining programs.

All states should create fast-track programs to ease onramps for people like my daughter who’ve earned degrees in other fields, whether they’re pivoting to health care early in their career or later in life. This means directing public nursing and allied health schools to develop targeted programs and harmonize prerequisite requirements.

In Annabel’s case, it didn’t make sense to attend nursing school in our home state of Texas because the state universities would have treated her as a first-year college student and required numerous extraneous prerequisites. She found that only a handful of highly selective private universities offer programs for people in her position, which is why she’s now in another state.

All states should enter into interstate compacts providing for common recognition of health care credentials across state lines, as some states have done for nurses but fewer have done for med techs. Every state legislature should follow the example of Arizona, Georgia, and a handful of other states in creating streamlined pathways for military veterans with relevant training to become licensed health care professionals. And all states should open simpler paths for foreign-trained health care professionals to put their skills to work, as Massachusetts has started doing with a 2022 initiative aimed at immigrant doctors and nurses.

West Coast University - Texas nursing pining ceremony in November 2022. (WCU-Texas/Facebook)

West Coast University - Texas nursing pining ceremony in November 2022. (WCU-Texas/Facebook)

In addition, states and employers should work together to build more seamless pathways for existing nurses and other health care professionals to move to higher levels of training, either through full-time study or part-time while working. Training levels make a difference.

Nurses with bachelor’s degrees, for instance, produce better patient outcomes than nurses with lower degrees and credentials. That’s why health care thought leaders called for raising the share of nurses with a bachelor’s degree or more to 80% from 50% today in the landmark 2010 report The Future of Nursing.

Policymakers can also expand the capacity of today’s health care workforce by using evidence to understand the best ways to widen scope-of-practice rules governing what nurse practitioners can do for patients. Most states have maintained obsolete and over-restrictive rules despite evidence that NPs in many settings deliver good patient outcomes, access, and cost containment. Congress should do its part by directing the Medicare and Medicaid systems to cover procedures legally performed by NPs, which they often don’t today.

Better culture and incentives

Third, decision-makers at every level should focus on improving work cultures for nurses and other health care professionals and addressing the perverse incentives that often afflict the sector. The epidemic of nurse resignations during the COVID-19 crisis dramatically illuminated the substandard working conditions millions of frontline caregivers face.

Expanding America’s health care workforce represents an achievable double-bottom-line proposition. It would help ensure the quality care Americans will need in coming decades and increase economic opportunity for millions of people.

Hospitals can increase retention rates considerably, studies show, by giving nurses more voice in hospital leadership, increasing professional development opportunities, and building more collaborative cultures – for instance, by having physicians and nurses go on rounds together.

Medicare and private insurers can also create better incentives for employers by instituting global or outcomes-linked payment systems, since current fee-for-service systems that don’t provide for specific services performed by nurses and other professionals incent hospitals to under-staff. Lightening excessive workloads is, in turn, one of the best steps employers can take to keep overburdened professionals in the health care sector.

Expanding America’s health care workforce represents an achievable double-bottom-line proposition. It would help ensure the quality care Americans will need in coming decades and increase economic opportunity for millions of people. The United States has countless individuals like Annabel with the talent, temperament, and idealism to become difference-makers in American health care. We should welcome them in.

The Catalyst believes that ideas matter. We aim to stimulate debate on the most important issues of the day, featuring a range of arguments that are constructive, high-minded, and share our core values of freedom, opportunity, accountability, and compassion. To that end, we seek out ideas that may challenge us, and the authors’ views presented here are their own; The Catalyst does not endorse any particular policy, politician, or party.