How the international order serves American interests

Before abandoning a system it helped create, the United States should remember how much it gets from an orderly world.

A British and U.S. soldier standing side by side after a press conference in Brueck, Germany on Feb. 26, 2020. (Soeren Stache / dpa via AP)

A British and U.S. soldier standing side by side after a press conference in Brueck, Germany on Feb. 26, 2020. (Soeren Stache / dpa via AP)

Throughout his political career, President Donald Trump has been very consistent about his dislike for the rules-based international order. His administration’s America First agenda is based on a transactional zero-sum view of the world, under which Washington should shake off its constraints – including norms, treaties, and trade deals – and use its power to its own narrow advantage.

Since taking office the second time, the president has moved at blistering speed to make this worldview policy. His tariffs and territorial claims on allies, his withdrawal from the World Health Organization (WHO), his shuttering of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and many other parts of the State Department – these and other moves aim to dismantle the international order, which he sees as rigged against the United States.

That order didn’t just spring out of nowhere, however. Nor was it imposed on Americans by an outside power. It was, on the contrary, painstakingly conceived of and carefully constructed by the United States and its friends. And that process wasn’t motivated by some misguided sense of charity in Washington. The rules-based international order was a carefully thought-through response to a long series of terrible events, an attempt to avoid repeating them, and a bet that the new system could create a better future.

Today, that system is at risk. Once gone, however, it will be hard if not impossible to recreate, since a key principle that underlies it – the reliability of the United States – is being questioned. Should the order fall, all the blood, treasure, and trust that Washington spent building it could be squandered.

If true conservatism involves an instinctive cautiousness toward radical change – “a disposition to preserve,” as Edmund Burke put it – now would therefore be a good time to pause and take a careful accounting of everything America has gained from the order it worked so hard to create. The math shows that the United States has benefited much more from it than it has lost. While the system is far from perfect, 80 years’ experience shows that the rules-based international system is a bit like Winston Churchill’s description of democracy: the worst way of doing things … except for all the others.

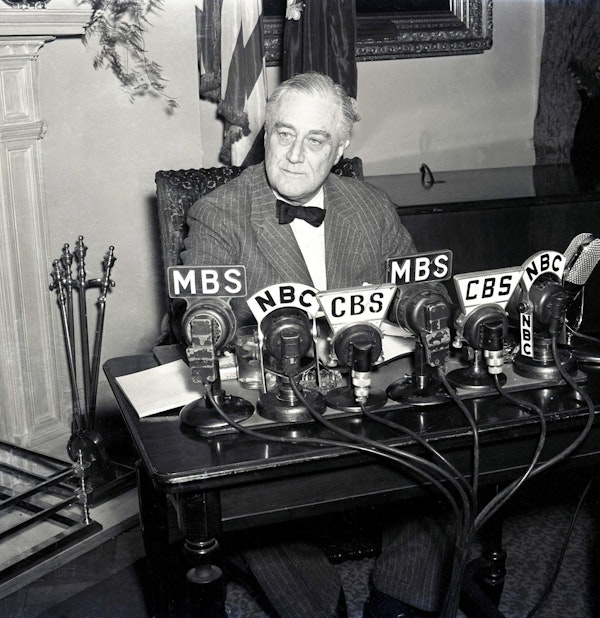

President Franklin Roosevelt addresses the nation two days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Dec. 9, 1941. (Icon and Image / Getty Images)

President Franklin Roosevelt addresses the nation two days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Dec. 9, 1941. (Icon and Image / Getty Images)

Present at the creation

In the early 1940s, having lived through a destabilizing global Depression and been sucked into two worldwide conflagrations, the United States was determined not to be burned again. Aiming to “win the peace” as well as the war – as President Franklin D. Roosevelt put it in a fireside chat just two days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor – Washington began working with its allies to create a new global network of institutions and alliances. The goal was simple, though the process would not be: to prevent a repeat of the conditions that had caused so much chaos and carnage in the preceding decades.

Over time, this system would come to include a wide-ranging set of agreements and organizations, including the United Nations and the International Court of Justice; NATO; a global financial system underwritten by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank; and a global trading system organized first through the Global Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and then, after 1995, the World Trade Organization (WTO). It would also include a long list of issue-specific, bilateral, and regional pacts and treaties, including the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty and the North America Free Trade Agreement (which was replaced by the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, or USMCA, in 2018).

The rewards delivered by this system, and the norms that underpin it, are hard to overstate. They have benefitted the whole world, delivering (among many other good things) the longest period of great-power peace in human history and the greatest run of economic development. But no country has done better under this system than the United States. The economic boom and the long great-power peace occurred – not coincidentally – during the most powerful phase in U.S. history, a time when the country led a growing alliance of mostly democratic nations to victory in the Cold War and then, after the fall of the Soviet Union, ascended to sole superpower status. By 1991, no one could match the United States’ wealth or military might. The same holds true today (although China may be catching up fast).

Because this record and the institutions that produced it are now being challenged, it’s worth reviewing these accomplishments in greater depth. Without grasping the breadth of all the good things the rules-based order accomplished, you can’t fully understand what we will lose if we abandon it today.

Let’s start with the material side. (The accounting that follows is not meant to be comprehensive – a complete summary would fill a very long book – but to highlight some of the biggest gains.)

The postwar global economic order created by the United States has, over time, produced a world of relatively free trade. President Trump loves tariffs and has often derided these trade rules for allowing other countries, especially China, to cheat without suffering any consequences. And he’s right that China and few other countries have engaged in some egregiously unfair trade practices. It’s also true, however, that the United States has still done extremely well under this system. (It’s also worth mentioning that the United States itself was a shameless rule breaker early in its history.)

Consider some data illustrating American growth. Between 1947 and 2016, average tariffs for industrial products among developed countries fell to about 5% from an average of 40%. This drop in trade barriers helped the United States become a dominant economic powerhouse. During the postwar era, real median family income in the country grew about eightfold, per capita GDP increased from about $1,300 to $81,000, and the total economy grew from $223 billion to $27 trillion. Although U.S. manufacturing has declined in recent decades, the country remains the third largest exporter of goods and services in the world, with foreign sales reaching a third of a trillion dollars per month in 2024.

Low tariffs have also afforded U.S. consumers access to low-cost, high-quality electronics, appliances, and other goods that have dramatically increased their buying power and, with it, their quality of life – even during periods when wages weren’t growing much. One study found that cheap imports have increased the buying power of the average American by $260 a month for every month of their life. Another showed that this phenomenon, which economists call “the Walmart Effect,” is progressive, meaning it benefits the poor more than the rich – at least 4.5 times more.

One other, underappreciated perk of global trade ties is that they buttress America’s geopolitical power. Two academics recently calculated that while a full-scale economic decoupling with China would hurt the United States, it would hurt China much more – 11 times more, to be precise. To demonstrate this discrepancy another way, they estimate that severing all economic links between the two economies would lower U.S. GDP by 3.6% – but Chinese GDP by 39.9%. (And remember, the Chinese economy is already in trouble.) That fact gives Washington a devastating weapon to wield against Beijing should it ever need to.

Walmart mobile app. (Tada Images / Shutterstock)

Walmart mobile app. (Tada Images / Shutterstock)

The multiplier effect

Long before President Trump entered the political scene, denouncing multilateral institutions like the U.N. – where the United States has lost some high-profile votes over the years – had become popular sport among American politicians, especially on the right. While these bodies can sometimes be frustrating to work with, however, it’s important to remember that international institutions give U.S. projects international legitimacy – which is why most U.S. presidents, including Republicans, have usually tried to work through these organizations. Most of these bodies also remain dominated by the United States and largely do its bidding.

American influence is even clearer in institutions such as NATO, which, as the journalist Steven Erlanger wrote recently, “was built as an American-dominated alliance, intentionally dependent on American leadership, sophisticated weaponry, intelligence and airlift.” NATO’s command structure is “essentially owned and operated by the United States,” he added. That’s guaranteed by the fact that, while NATO’s top civilian job is always held by a European, its top military post – Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) – is always an American.

So, for that matter, is the head of the World Bank. And even international bodies not formally led by U.S. citizens also usually do what the United States wants. While there are exceptions, such as the U.N. Human Rights Council, even the U.N. Security Council has backed far more U.S. initiatives than it has opposed.

International organizations and treaties help the United States in another critical way: by sharing the costs of keeping the peace. Remember that the first hot battle of the Cold War, Korea – which broke out just five years after the end of World War II – was fought under U.N. auspices, and that 15 other nations sent their soldiers to fight alongside American GIs. The international mission to stabilize Afghanistan after 9/11 also started as a U.N. project. These and other efforts, which reinforced norms like territorial sovereignty by punishing international aggression, have made the world safer for everyone. They have prevented lots of bad things – death, destruction, and foreign oppression – and facilitated many good ones, such as international trade and economic development.

While many Americans assume that the costs of such projects are disproportionately borne by the United States, the truth is more complex. It’s true that many U.S. allies, NATO members, and non-NATO partners like Japan don’t currently pay enough for their own defense. But the balance was shifting in the right direction long before President Trump first took office. A recent study commissioned by the Office of the U.S. Secretary of Defense found that, since the end of the Cold War, the share of total allied defense spending shouldered by the United States has decreased significantly, to 39% from 53%.

Critics also generally overlook the fact that much of the military support the United States gives to other countries ends up pouring back into the U.S. economy. One recent example: As my colleagues Ken Hersh, Igor Khrestin, and David J. Kramer have pointed out, close to 70% of the monetary aid the United States has sent to Ukraine for its defense against Russia has been spent in the United States or on U.S. forces.

It’s also important to remember that mutual defense treaties don’t just help other countries. They act as force multipliers for the United States, keeping it much safer for much less money than the country would have to spend to do this work on its own. Remember that NATO has invoked Article V of its charter – which compels all members to treat an attack on one as an attack on all – exactly once in its history: following the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the United States.

In fact, allies and alliances help protect the United States in many ways. More than 80 other countries currently allow the U.S. military to base troops and equipment on their territory, for example. Such arrangements let the United States to position its forces near critical chokepoints, such as the Suez Canal and the Strait of Malacca, that are important to the U.S. and global economies. They also provide Americans with what experts call “defense in depth.” By positioning its military assets on the doorsteps of its adversaries (whether great powers like China and Russia or terrorists in the Sahel or the Middle East), Washington gains early warning systems and is able to strike threats quickly and where they appear – far from the U.S. homeland. The costs of such bases, moreover, are often exaggerated. Many U.S. allies actually help pay for the American military assets stationed on their soil – payments that, in the case of South Korea and Japan, reach billions of dollars every year.

America’s allies also directly provide the United States with critical intelligence – operating, essentially, as eyes and ears around the world. These arrangements can be bilateral, as in the case of Israel, or multilateral, as in the case of Five Eyes, a post-World War II alliance among Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. All in all, the United States now enjoys intelligence-sharing agreements with at least 41 other countries, greatly increasing its ability to monitor the world for threats and opportunities – and for very little money.

Finally, America’s security partnerships with countries around the globe have helped limit the spread of history’s most destructive force: nuclear weapons. Because the United States promised to underwrite their security, U.S. allies such as Australia, Egypt, Germany, Japan, South Korea, and Saudi Arabia have never developed nukes of their own – despite the fact these countries live near hostile nuclear powers. Yet such restraint may now be evaporating. As I recently argued elsewhere, the great success of the U.S-led nuclear nonproliferation system is being undermined by questions about America’s commitment to Ukraine (the security of which it explicitly guaranteed in 1994), as well as its criticisms of NATO partners and its aggressive designs on Canada and Greenland.

President George W. Bush makes remarks at The AIDS Support Organization Centre in Entebbe, Uganda, on July 11, 2003. (George W. Bush Presidential Library)

President George W. Bush makes remarks at The AIDS Support Organization Centre in Entebbe, Uganda, on July 11, 2003. (George W. Bush Presidential Library)

Ideas in action

One other aspect of the international rules-based system deserves highlighting here for the way it has disproportionately benefited the United States: the norms that underlie it. Ideas like the reliability of the United States (discussed above), adherence to the rule of law, respect for individual rights, a preference for the peaceful settlement of disputes, and the sanctity of national borders may sound like abstract concepts. But all of them have produced very solid results.

In the 80 years preceding World War II, Europe was the most militarized region on the planet and fought at least 10 major interstate wars – wars that had a nasty way of sucking in outsiders (more than half a million U.S. troops were killed in the two world wars, for example). In the 80 years since 1945, by contrast, Europe has become the least militarized region on the globe and has suffered only two or three conflicts, depending on how you count them. That remarkable record can be attributed to numerous factors, including the economic integration of former enemies (through the European Economic Community, which evolved into the European Union) and military unification (through NATO). But those institutions all rely on shared faith in the values mentioned in the previous paragraph.

Since 1945, America’s championing of those values, along with the popularity of its culture, has also granted the United States enormous reserves of what political scientists refer to as “soft power” – the ability (in the words of the Harvard professor Joe Nye, who coined the term) “to obtain preferred outcomes by attraction rather than coercion or payment.” Note the second half of that phrase: It means that over the last eight decades, the United States has often been able to get what it wants in international relations without paying for it, because other countries have wanted to cooperate with Washington. And that’s been because they had faith in U.S. intentions, because they admired U.S. political values, and because they felt that U.S. foreign policy goals were legitimate and worth supporting.

International peacemaking – think of the U.S. roles in the Korean War or, more recently, the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia and Afghanistan – contributed to this consensus. So did U.S. foreign assistance programs in areas such as public health (through the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, or PEPFAR, for example), education, good governance, and democracy promotion. All these projects have allowed the United States to accomplish important priorities without having to twist arms or deploy economic or military weapons – tools that are much more expensive to use. Put simply, preventing wars is much cheaper than fighting them. This is what General James Mattis, then head of U.S. Central Command, was referring to when he told Congress in 2013, “If you don’t fund the State Department fully, then I need to buy more ammunition.” Or why two other senior U.S. generals recently warned, “Withdrawing from America’s leadership role on the global playing field risks leaving a void for our adversaries to fill.”

It remains to be seen whether the Trump Administration means to reform the international order or completely revolutionize it. Skeptics of the rules-based international order argue that the benefits outlined above are overstated, that the United States could save huge amounts of money and effort by abandoning it, and that the United States could gain far more through the direct application of raw power.

But such ideas are exactly what defined the international system for most of human history leading up to 1945. And those centuries were characterized by near-universal poverty, very short lifespans, near-constant warfare, and enormous amounts of human misery. Life was nasty, brutish, and short. Do we really want to risk the peace and plentitude of the last 80 years and return to that?

The Catalyst believes that ideas matter. We aim to stimulate debate on the most important issues of the day, featuring a range of arguments that are constructive, high-minded, and share our core values of freedom, opportunity, accountability, and compassion. To that end, we seek out ideas that may challenge us, and the authors’ views presented here are their own; The Catalyst does not endorse any particular policy, politician, or party.