Freedom abroad protects freedom at home

The fight for human rights is both a moral imperative and the key to ensuring a strong, secure, and prosperous United States.

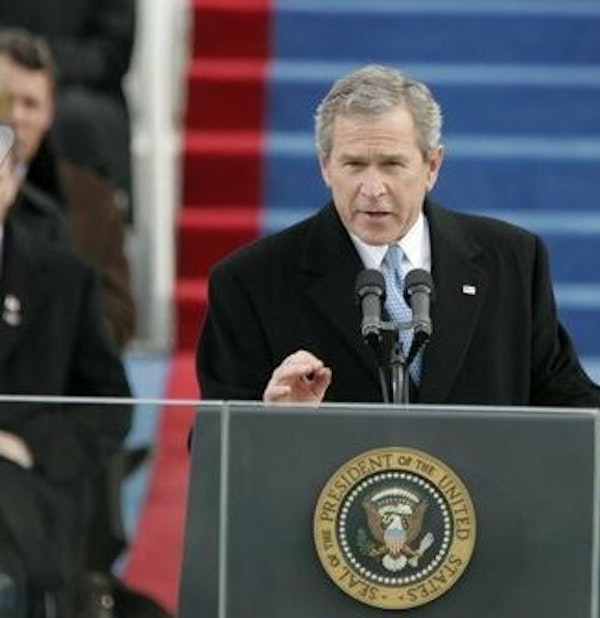

President George W. Bush delivers his second Inaugural address in Washington, DC on Jan. 20, 2005. (Paul Morse / White House Archives)

President George W. Bush delivers his second Inaugural address in Washington, DC on Jan. 20, 2005. (Paul Morse / White House Archives)

In every corner of the world today, the defenders of human rights are fighting for the most basic freedoms. Whether sitting in an office, a prison, a church, or in hiding, these courageous activists are working tirelessly to advance democracy and liberty against autocratic governments, criminal gangs, oligarchs, and terrorist organizations.

The United States long considered such fighters to be its allies. This alignment was not based on a sense of charity, but rather a recognition that America’s own freedom, security, and prosperity are deeply tied to the freedom of other peoples and countries around the world. Those fighting for human rights abroad share many of our core values, and their work benefits vital U.S. interests. In the past, most American policymakers understood that supporting them was therefore consistent with the founding principles and strategic interests of the United States. As President George W. Bush put it in his second inaugural address, “The survival of liberty in our land increasingly depends on the success of liberty in other lands. The best hope for peace in our world is the expansion of freedom in all the world.”

Today, the consensus surrounding these ideas is eroding, and the United States has begun backing away from some of these long-held values. In recent months, it has deprioritized human rights and democracy in U.S. foreign policy, shown support for undemocratic leaders, and cut foreign assistance – including aid to democracy activists around the world. In doing so, however, Washington is not only abandoning allies, but also weakening a key weapon in the fight against authoritarianism.

A conservative internationalist view of foreign policy understands the fight for human rights to be both a strategic tool and moral imperative and recognizes that protecting such rights is crucial to ensuring a strong, secure, and prosperous United States anchored in core American values. Without such a strategic understanding, human rights risk becoming a political football in the struggle between progressives and the Trump-aligned right, which could diminish their importance in the eyes of many Americans to U.S. security, prosperity, and opportunity. The United States must resist this polarized debate and recapture the principles that have traditionally underpinned its approach to the world. Should it fail, it risks damaging American interests and values and compromising our moral standing around the globe.

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt holds up a copy of The Universal Declaration of Human Rights circa 1947. (Fotosearch / Getty Images)

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt holds up a copy of The Universal Declaration of Human Rights circa 1947. (Fotosearch / Getty Images)

The case for values and interests

Scholars and policymakers have long debated the tradeoffs between values and interests, often pitting the two against one other and suggesting that they are not compatible. One can either support human rights and deprioritize security or economic interests or uphold security and economic interests at the expense of values. But neither binary is accurate.

U.S. foreign policy must protect the security and economic interests of the country and also remain faithful to America’s founding principles. The United States faces significant threats from autocratic nations such as China, Iran, Russia, and North Korea, which are determined to degrade American power and influence and replace the rules-based order with one dominated by dictators. It is no coincidence that America’s greatest adversaries are nondemocracies, countries that devalue the rule of law, human dignity, and peace. These nations make the United States less safe through attacks on democratic institutions around the world, threatening or invading neighboring countries, supporting extremism, manipulating the information sphere, and violating global norms.

A key part of the strategy for defeating these powers and maintaining U.S. global leadership is aligning ourselves with others who are also committed to standing up against autocrats – and human rights defenders are central to this process. These activists include journalists who uncover and report on the abuses of such regimes. They include members of the political opposition, who represent the true interests of their fellow citizens and offer a path to responsible and accountable governance. They include faith and civil society leaders, who uncover limitations on freedoms and challenge unjust rulers. Such individuals have brought dictatorships to their knees in the past. These are the kind of activists that President Ronald Reagan, President George W. Bush, and Senator John McCain regularly called out by name and met with when they could.

Indeed, for many decades, support for human rights was embraced by internationalist American conservatives, who advocated for a U.S. foreign policy grounded in individual liberty, the rule of law, and peace through strength. Conservatives believe that all people are created equal and should continue to champion the freedoms of conscience, speech, and religion as part of the larger global conflict against autocracy. Yet in recent years, many U.S. conservatives have reduced their focus on human liberty, ceding the ground to progressives – who sometimes approach human rights in a different way – or Trump-aligned policymakers who have jettisoned this important part of U.S. foreign policy.

A female demonstrator raises her fists during a demonstration to mark the first death anniversary of Mahsa Amini in Washington, DC, on Sept. 16, 2023. (Probal Rashid / LightRocket via Getty Images)

A female demonstrator raises her fists during a demonstration to mark the first death anniversary of Mahsa Amini in Washington, DC, on Sept. 16, 2023. (Probal Rashid / LightRocket via Getty Images)

A dangerous decline

The decline of human rights as a focus of U.S. foreign policy can be attributed to several trends. Core among these is the debate about whether the United States should support democracy globally. In recent years, there has been an erosion in support for the belief that a world full of democracies would be beneficial to U.S. interests, while the alternative – a world dominated by an increasing number of autocrats – would be a huge threat. In some progressive circles, democracy has become a bad – or less used – word, due in part to the belief that supporting democracy forces U.S. or Western values or structures on other nations. What this view overlooks is that human rights activists in many other countries often look to established democracies for support for their local movements. From China to Iran to Venezuela to Zimbabwe, activists risk their lives and livelihoods fighting for democracy because they know it is the best system – not because it is an American or Western imposition.

A related trend, which can be seen in both some progressive and far-right circles, is the false association of U.S. support for democracy with the use of force, military intervention, and an excessively aggressive and expensive U.S. foreign policy. Democracy cannot be supported or advanced through military means; external actors can only support what local activists and democratically oriented leaders are already doing. When there are political transitions abroad, the United States should support democracy because democracy remains the best – and only – governing system for protecting human rights and liberty, with built-in self-correcting mechanisms that allow it to address its own shortcomings.

Both trends are leading the United States to increasingly separate human rights from democracy and from our security and economic interests. But we separate these issues at our peril.

Beyond the debate about democracy, there has been a notable shift to the left in the human rights community over the last two decades, which has often made moderates and conservatives more reticent to make support for human rights a key part of U.S. foreign policy. Indeed, this shift has been used as a pretense by those who want to eliminate human rights from U.S. foreign policy altogether.

Several factors have contributed to this shift. A relatively recent emphasis on climate concerns as human rights issues has detracted from a focus on the core human rights that autocratic governments undermine daily. While protecting the climate and addressing climate change are important, the elevation of an issue that is not itself a human right to the center of the debate has not helped the cause.

In a similar vein, progressives’ emphasis on the rights of specific groups – particularly the LGBTQI+ community – has skewed the focus of the field, distracting from the many other groups also targeted as much or more by authoritarian regimes – groups that include religious adherents, journalists, women, and political opponents. To be clear, the abuse and violence faced by LGBTQI+ people around the world unquestionably is a human rights issue; the question is how much focus this problem should receive.

A third factor in the leftward shift of much human rights discourse has been an overreliance on international organizations and instruments to advance the cause. While the United Nations, drawing at times on the U.S. Constitution, has driven the codification of many global human rights standards, the membership and conduct of many of the organization’s human rights bodies – especially the U.N. Human Rights Council – has left a lot to be desired. In recent decades, governments notorious for abusing human rights, such as China, Egypt, Russia, and Venezuela, have won seats on the Council, then used them not to advance the Council’s mandate but to protect themselves and other autocrats from critique and to bash Israel, a U.S. ally and the only democracy in the Middle East. This process has made a mockery of a system intended to serve human liberty and global peace. While the United States should not abandon the international system that it helped build, it should engage in multilateralism only when principled, effective change is possible. When it is not, it should work among ad hoc coalitions of countries as a more effective means of driving action.

Protestors supporting Hong Kong’s “Umbrella Movement” for human rights in Manchester, UK on June 9, 2024. (Ashley Chan / SOPA Images / LightRocket via Getty Images)

Protestors supporting Hong Kong’s “Umbrella Movement” for human rights in Manchester, UK on June 9, 2024. (Ashley Chan / SOPA Images / LightRocket via Getty Images)

Upholding the order

Following World War II, the United States led the creation of a new international system based on democratic values, the respect for human rights, free trade, alliances among democracies, and rules that promote order and discourage conflict. In the eight decades since, many countries have benefited from this system, imperfect as it is – and none more than the United States.

Over these years, most American leaders have understood that respect for human rights is a core part of this system, and that, by defending human rights around the world, they could help support an order that ultimately benefited the United States itself. President Reagan, for example, clearly recognized this link. As he reminded Americans in a 1986 speech, “we’ve learned through painful experiences that respect for human rights is essential to peace and, ultimately, to our own freedom. A government which does not respect the rights of its own people and laws is unlikely to respect those of its neighbors.”

He and other U.S. presidents understood that support for human rights globally must be a core element of U.S. foreign policy. His and other administrations sought to advance human rights through rhetorical support for activists, funding human rights programs, advocating for the release of political prisoners and the protection of repressed populations, economic statecraft, and multilateralism.

Retreating from this work today will threaten U.S. security by weakening those who oppose autocracy. It will also allow our adversaries to grow stronger. Autocrats understand this fact, which is why they have welcomed recent U.S. moves to dismantle the American institutions that support human rights.

These moves also risk eroding America’s well-earned global reputation as a leader that stands for freedom, democracy, and human rights. For decades, that reputation has helped strengthen the United States’ political and security alliances. Damaging it now will diminish America’s strength in its geostrategic fight against adversaries such as China, Iran, and Russia.

The opportunity ahead

The United States, its political parties, and the entire global system are currently in a state of flux. While unnerving, this transition also gives the United States an opportunity to reclaim the principles that must shape its foreign policy.

Americans retain many powerful tools, should we choose to use them. One of the most impactful ones is our voice. From President Reagan to President Bush to Senator McCain, many U.S. leaders have used the bully pulpit to great effect in calling for the release of political prisoners, condemning genocide and the abuses of minorities, and urging respect for fundamental rights. Our current leaders – in Congress, the business world, civil society, and the media – should follow this well-trodden path, particularly if the administration chooses not to champion American values and security.

The United States must also maintain its financial, rhetorical and political support for human rights advocates. For years and at minimal cost, the U.S. government has provided lifesaving help and training for activists working to counter authoritarianism. So far, the Trump Administration has indicated that it is unwilling to continue such support or to prioritize the values that underlie them. During the first Trump Administration, conservative members of Congress stepped in to ensure that U.S. support for democracy globally would not wane. They have another opportunity to do so today.

Whether through Congress or the administration, the U.S. government must reassure its democratic allies and the rest of the world that the United States has not abandoned its core values. With autocratic countries fighting to end U.S. global leadership, the United States must break out of its dangerous either-or mentality, in which too many of us see a binary choice between embracing the progressive human rights agenda or abandoning those rights entirely. The protection of human rights globally is a long, honorable, and bipartisan American tradition, one fundamental to our values, security, and prosperity.

The Catalyst believes that ideas matter. We aim to stimulate debate on the most important issues of the day, featuring a range of arguments that are constructive, high-minded, and share our core values of freedom, opportunity, accountability, and compassion. To that end, we seek out ideas that may challenge us, and the authors’ views presented here are their own; The Catalyst does not endorse any particular policy, politician, or party.