America First needs American values

U.S. foreign policy works best when it recognizes that power and idealism go hand-in-hand.

Civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King, leading the Selma to Montgomery march, March 1965. (Abernathy Family Photos)

Civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King, leading the Selma to Montgomery march, March 1965. (Abernathy Family Photos)

The free world is the outer perimeter of American security, an engine of American prosperity, and a megaphone for American influence. U.S. foreign policy should aim to preserve, protect, and defend the free world.

That may sound obvious. That is because it was obvious to most U.S. voters and policymakers from 1945 to 2016. Even well before World War II, many American leaders envisioned the United States as an “Empire of Liberty” (in Thomas Jefferson’s phrase) and a proverbial city on a hill whose moral example meant something on the world stage.

That consensus has collapsed over the past decade. For the first time in generations, it is now necessary to make the case for U.S. leadership of the free world. Americans should still embrace a foreign policy that defends U.S. interests and U.S. values alike, that supports free trade with free nations and cooperative security with fellow democracies. U.S. foreign policy works best when it rests on the premise that American power and American idealism go hand in hand.

The American project

The “free world” is the world made up of a set of countries and a set of principles, including democracy, human rights, free trade, the sanctity of contracts, the freedom of the seas, and the peaceful adjudication of disputes. It means comity and equality among countries, selective cooperation with responsible international institutions, and collective security among democratic allies. The free world is responsible for an unprecedented stretch of peace among great powers and an explosion of human prosperity and innovation.

It is true that the free world comes with rules that restrict American choices. But what critics fail to appreciate is that the United States wrote the rules. The free world is not a globalist infringement on American sovereignty. It is an American export to make the world friendlier to us. The United States invented it with American ideals, pushed it on the world through American power, and has upheld and maintained it with American diplomacy.

The United States lives by its rules so that everyone else will do the same. Better to accept the limits of a few rules in exchange for the world’s voluntary buy-in than to break the rules, set a precedent everyone else will follow, and pay the cost of a much more hostile world order. Having built the free world, it would be odd, not to say self-destructive, for the United States to turn its back on it now.

President Donald Trump’s alternative foreign policy rests on a combination of nationalism, mercantilism, and so-called realism, (or restraint), a new triad to replace President Ronald Reagan’s fusion of free markets, social conservatism, and conservative internationalism. But none of this new triad’s legs stand up.

Mercantilism may protect a few legacy industries, but it will make everyone poorer with more expensive goods, higher trade barriers, and frayed partnerships. At home, nationalism is illiberal and a poor fit with America’s pluralism and its traditions of liberty and equality for all. On the world stage, nationalism is needlessly belligerent, overly concerned with greatness and not concerned enough with goodness. And it would overlook the United States’ genuine interests. What pressing American interest demands ownership of Greenland or Panama when the NATO alliance, the Panama Canal Treaty, and various trade agreements have already given us what the United States needs?

Nationalism also sits in tension with the last leg of President Trump’s new stool, restraint. Even as the Trump Administration talks about ending the war in Ukraine, it is acting in notably unrestrained ways elsewhere – offering to take over Gaza, bombing Yemen, or threatening Canada, for example. The White House also does not seem to recognize that if it tears down the current international system, the result may be something far worse: a Chinese-led world order.

President Trump has been commendably hawkish toward China – his trade restrictions on the country and his recognition that we have entered an era of great power competition were steps in the right direction. But his administration seems to misunderstand the nature of that competition and how to win it. Pushing U.S. dominance simply because it is American is not an effective way to sell that dominance to the rest of the world. Ever since World War II, the many countries that have sided with the United States in various conflicts and initiatives have done so because Washington always offered more than just its own hegemony. American policymakers framed U.S. leadership as part of a system of ordered liberty. If the United States now abandons that tradition, it is likely to lose allies and lose influence – and China will step in and fill the gap.

Theodore Roosevelt and the Rough Riders after the battle of San Juan Hill, Cuba on July 1, 1898. (Library of Congress)

Theodore Roosevelt and the Rough Riders after the battle of San Juan Hill, Cuba on July 1, 1898. (Library of Congress)

Born free

When U.S. grand strategy focuses on the free world, it carries on the best of America’s foreign policy traditions. The country’s founders put the “Law of Nations” into the U.S. Constitution (Article I, Section 8), authorizing themselves to enforce it. They intended to make principles like freedom of the seas and free trade core parts U.S. foreign policy, and the United States fought two early conflicts – the Barbary Wars and the War of 1812 – in part to defend these ideas.

While advocates of restraint love to quote John Quincy Adams’ line from 1821 that America “goes not abroad, in search of monsters to destroy,” they miss the context of his comments. It was a Fourth of July speech, celebrating America’s birthright of liberty – which he recognized was grounded in universal claims. America has “proclaimed to mankind the inextinguishable rights of human nature, and the only lawful foundations of government,” Adams said. American diplomacy speaks in “the language of equal liberty, of equal justice, and of equal rights.” That is why “wherever the standard of freedom and independence has been or shall be unfurled, there will her heart, her benedictions and her prayers be” and why America is the “well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all.” Far from announcing a doctrine of restraint or a policy of disinterest towards the fate of liberty abroad, Adams was declaring that he saw the world as divided between the free and unfree. And he left no doubt as to which side the United States was on.

It took the Civil War to cement the idea that freedom and equality truly are at the core of American identity, after which the United States pushed outward. It built a New Navy in the 1880s to announce American power to the world. The United States fought a war with Spain in 1898 and mounted the first modern humanitarian intervention in Cuba, helping enslaved Cubans rebel against their Spanish overlords. Once there, the United States cleaned up the streets, vaccinated the population, held four elections in four years, and left – in sharp contrast to the Europeans, who typically used such interventions as a guise for extending or maintaining their empires. The United States did build an empire of sorts, most notably by occupying the Philippines for 50 years. Today, however, few other countries have a more favorable view of the United States, according to the Pew Research Center. Even episodes of misguided American imperialism proved exceptional.

The United States fought the Great War under the banner of Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points. Wilson was an incompetent diplomat who put too much faith in the potential of the League of Nations, but the animating principles behind his Fourteen Points were sound: open diplomacy, no secret treaties, free trade, the rejection of territorial conquest, and self-determination. It was an early vision of what ordered liberty among nations could look like.

That first effort to realize that vision died in its infancy, suffocated by pacifism, isolationism, and utopianism before it was strangled by the Nazi Reich and Empire of Japan. But President Franklin D. Roosevelt and U.K. Prime Minister Winston Churchill made sure to keep the vision alive by fighting the Second World War under the banner of the Atlantic Charter, which repeated Wilson’s themes. A declaration of war aims, it was also a declaration of what the United States intended to live for, what kind of world Americans would build in the war’s aftermath. The charter is the birth certificate of today’s free world order.

Instead of racial hierarchy, Americans would work for equality – as they did through the Civil Rights Movement. Instead of zero-sum mercantilism and protectionism, the United States would embrace free trade and bank on its positive-sum, win-win promises – as the country did through the Global Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and later the World Trade Organization. Instead of going it alone, the United States would stick by its allies and partners, as it did in creating NATO in 1949. Above all, instead of the pacifism and the disarmament movement that was fashionable in the interwar years, the United States would project strength with a professional military and national security apparatus. “Peace through strength” was America’s conservative internationalist policy long before President Reagan popularized the term.

When faced with disputes, as the United States often was with the Soviet Union, instead of conquest and aggression, it would first try diplomacy and treaties. This approach sometimes succeeded, as with the talks that led to several treaties limiting nuclear weapons. Diplomacy is not weak – it does not need to meet the fate it did under President Wilson – so long as it abides by another conservative internationalist adage: trust but verify.

The high points of U.S. foreign policy have always matched American idealism with American power. Too much idealism without power leads to ineffective utopianism. Too much power without idealism leads to unnecessary adventurism. Working together, American power and American ideals are the twin pillars of the U.S.-led free world order. They are mutually constitutive and mutually reinforcing. American power upholds the free world, and the free world enhances and extends U.S. power. This virtuous cycle has maintained relative peace and prosperity for the better part of a century.

Ideals in action

How would a conservative internationalist foreign policy approach the world’s crises and opportunities today?

A conservative internationalist outlook starts with the premise that the free world is the outer perimeter of U.S. security. When a sovereign country, especially an emerging democracy, is invaded, the whole world’s freedom is threatened. The war in Ukraine is not just about the borders of a country on the other side of the world. It is about the principles of sovereignty and nonaggression. Defending Ukraine means defending the farthest outpost of the free world on the frontline against tyranny and aggression. It is the first major battle of the new Cold War.

A conservative internationalist approach understands that the best route to a just peace is to arm and assist Ukraine to maximize its leverage on the battlefield, because battlefield success translates into negotiating leverage. The United States should sustain its commitment to Ukraine’s defense, opening talks with Russia only after Ukraine has regained momentum.

The next battle of the new Cold War may be over Taiwan. The threat of a rising China is so clear that it seems to have concentrated minds on both sides of the aisle, giving China policy comparatively greater coherence – and a more conservative internationalist tinge – than other areas of U.S. foreign policy. Presidents Trump and Biden both rightly continued the United States’ decades-long policy of selling weapons to Taiwan while insisting on a peaceful resolution to China’s claim on the island. President Trump allowed the highest-level contacts between the U.S. and Taiwanese governments since 1979, increased weapons sales, and continued the Obama-era Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy.

A conservative internationalist strategy would continue these elements while also emphasizing that U.S. support for Taiwan is not a product of cynical geopolitics; it is based on the principle that democracies support one another. Washington should similarly give support to pro-democracy dissidents in Hong Kong in order to emphasize the contrast between itself and the authoritarian regime in Beijing.

The last major crisis in the world today is the series of connected conflicts that stretch across the Middle East: Israel and Palestine, Saudi Arabia and Iran, and those created by Iran’s proxies in Yemen, Syria, elsewhere. No U.S. policymaker has covered themselves in glory trying to manage the region’s complexities, but virtually all of them understand that the least plausible solution today would be for the United States to take control of Gaza. President Biden rightly sustained U.S. support for Israel in the face of mounting opposition from his own party and within his own State Department, for which he deserves credit. He also applied behind-the-scenes pressure on Israel over some of Israel’s less cautious wartime choices – again, appropriately. But the biggest and most important issue still looms: what to do now?

After the attacks of Oct. 7, 2023, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu reversed decades of Israeli policy by taking the two-state solution off the table. Israel had just cause to destroy Hamas and recover hostages. But having removed a government from power, Israel is on the hook for what’s next. Who and what will govern Gaza?

A conservative internationalist approach understands that the war should have been fought to liberate Israel and Palestine alike from Hamas’ tyranny and terror, paving the way – someday – for the emergence of a sovereign and accountable Palestinian state alongside a sovereign and secure Israel. That is what the broad outlines of justice and peace demand, no matter how unlikely such an outcome seems today. The fact that the two-state solution is almost inconceivable now makes it all the more important to reaffirm it as an eventual goal to guide diplomatic efforts.

But whatever happens in Gaza, the Middle East will not find stability until the regime in Iran falls or is fundamentally transformed to accept Israel’s existence and Saudi Arabia’s interests, and to foreswear terrorism and nuclear proliferation. A conservative internationalist would have seen the Green Movement in 2009, the Arab Spring in 2011, and the 2022 Iranian uprisings as generational opportunities to topple or transform the Iranian regime. Only the Iranian people can make that happen, but the United States could have given them more diplomatic and rhetorical support. The Iranian government lacks popular support and legitimacy, and the Iranian people clearly want more transparent, more effective, and more accountable governance. Washington could aggressively name and shame Iran’s crimes on the world stage, restart Radio Free Europe-Radio Liberty’s Persian broadcasting, and restart democracy training programs for dissidents and emigres with the intent of catalyzing a democratic movement in the Middle East.

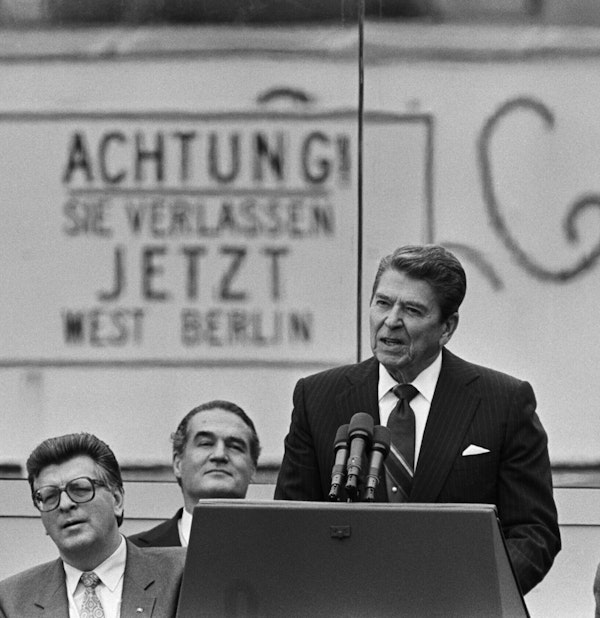

President Ronald Reagan, making his famous challenge to Mikhail Gorbachev to tear down the Berlin Wall on June 12, 1987. (Bettmann / Getty Images)

President Ronald Reagan, making his famous challenge to Mikhail Gorbachev to tear down the Berlin Wall on June 12, 1987. (Bettmann / Getty Images)

A higher calling

Democracy is central to U.S. ideals, U.S. identity, and America’s role in the world. It is why much of the rest of the world has put up with U.S. leadership for so long – and even asked for it when Americans hesitated. The rest of the world understands that democracy means peace and prosperity. Democracies don’t fight one other, they don’t export terrorism, and they don’t conquer and annex territory. Instead, they free their people to innovate, trade, and prosper, and they trade together, collaborate together, and converge on a common view of the world. The most obvious truth of foreign policy, the one that should serve as the polestar for U.S. grand strategy, is that the spread of democracy is good for American interests.

The pro-democracy agenda is also achievable and realistic, despite what some self-styled realists say. When Jefferson wrote of “self-evident” truths, they were only evident to him and a select few elites in British and American society. Today, about half the world is governed by those ideals, and the rest wishes it was. The only people who dislike liberty and equality are the self-interested rich men who hail from a ruling tribe. Everyone else – women, the poor, ethnic and religious minorities, and rich ruling men with a conscience – understand that accountable governance is their best shot at decent government. There is nothing uniquely Western about not wanting to be oppressed. As President Reagan said in 1982, “Freedom is not the sole prerogative of a lucky few, but the inalienable and universal right of all human beings.”

That idea has foreign policy implications. The United States has been, and should remain, on the side of legitimate, accountable governments that respect human dignity and protect human liberty and equality. Washington should deal with everyone as necessary, but it should align itself and its power with those that see the world the way Americans do.

The highest calling of statesmanship, as the ethicist Paul Ramsey once wrote, is to align the national interest with the international common good, insofar as is possible. When the two align, there is no tradeoff between what is good and what is strategic, between what is just and what is pragmatic, or between what is right and what is selfish. Using American power to uphold ordered liberty among nations – democracy, capitalism, and collective security – is how the United States aligns its interests with the international common good. An unfree world is unsafe for the United States; an unfree world is a poorer world for the United States. If we truly want to put “America First,” the most effective way to do that is to preserve and uphold the free world that the United States built and from which all Americans benefit.

The Catalyst believes that ideas matter. We aim to stimulate debate on the most important issues of the day, featuring a range of arguments that are constructive, high-minded, and share our core values of freedom, opportunity, accountability, and compassion. To that end, we seek out ideas that may challenge us, and the authors’ views presented here are their own; The Catalyst does not endorse any particular policy, politician, or party.