People and Place: Building Better Transportation Systems

For many low-income individuals the problem is not finding employment, but rather having the means to get there. Outdated public transportation systems and isolated communities make getting to high-paying jobs a job of its own.

A traffic jam forms outside of downtown Dallas in April 2016. (Shutterstock)

A traffic jam forms outside of downtown Dallas in April 2016. (Shutterstock)

I recently read an article that summed up the path that some people feel they are on in their lives. This part particularly stood out to me:

“For most of us, childhood is kind of like a river, and we’re kind of like tadpoles. We didn’t choose the river. We just woke up out of nowhere and found ourselves on some path set for us by our parents, by society, and by circumstances. We’re told the rules of the river and the way we should swim and what our goals should be. Our job isn’t to think about our path — it’s to succeed on the path we’ve been placed on, based on the way success has been defined for us.”

Of course, not all Americans see themselves as tadpoles limited by the river where they were born. A 2014 Pew Researchsurvey revealed that 57 percent of Americans disagree with the statement: “Success in life is pretty much determined by forces outside our control.” And 73 percent of Americans responded that it is very important to work hard in life to get ahead.

The impact of place

Working hard is indeed important, but, for many Americans, that is not enough to get ahead. Try as they might, some people, like the tadpole, are not the masters of their own fates.

Like it or not, where a person is born and ultimately lives is a major determinant of successful social and economic outcomes. Economic research shows “place” puts a geographical limitation on opportunity.

Like it or not, where a person is born and ultimately lives is a major determinant of successful social and economic outcomes.

Consider the limitations “place” puts on some people born in Dallas. By all measurements, Dallas has one of the strongest economies in the nation. In fact, a 2017 report from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics says Dallas has the highest job growth rate in the U.S. Additionally, the Dallas-metro area boasts a 10 percent population growth since 2010, one of the highest in the country.

Still, Dallas has one of America’s largest wealth gaps. In 2018, the Urban Institute ranked it dead last among the 274 largest U.S. cities for economic inclusiveness. Some Dallas residents have benefited enormously from the post-recession economy, which is reflected in a rise in real estate values and low unemployment. But Dallas’ poverty rate continues to increase with 23 percent of its residents living below the poverty line, well above the national average of 15 percent.

Some people may find it difficult to understand this disparity when so many people are doing well, jobs are growing, and the population is on a growth curve. But the imbalance exists, and one of the most pernicious factors is the lack of proximity for some Dallas residents to jobs that pay a living wage.

If you live in some parts of long-neglected southern Dallas, you are unlikely to live near many jobs. This is a reality we delved into while I was president of the Mayor’s Star Council, an organization of young Dallasites devoted to improving our city. Southern Dallas has seen a decline in job growth of 16 percent since 2000, even as the area’s population has grown more than 7 percent. Mayor Mike Rawlings’ GrowSouth initiative has seen some success in attracting new employment into parts of southern Dallas, including such employers as Walmart. But people still can work full-time in low-wage jobs, ones that tend to lack important benefits, and not earn enough to lift their family out of poverty.

Transportation is a barrier

One clear reason some struggle to get a decent-paying job is they often rely on transportation systems that do not connect enough workers to jobs in a reasonable time period. According to the University of Texas at Arlington’s Institute of Urban Studies, more than 65 percent of Dallas residents who live in the part of the city that is most dependent upon buses and rail lines can only get to about to 4 percent of regional jobs in 45 minutes.

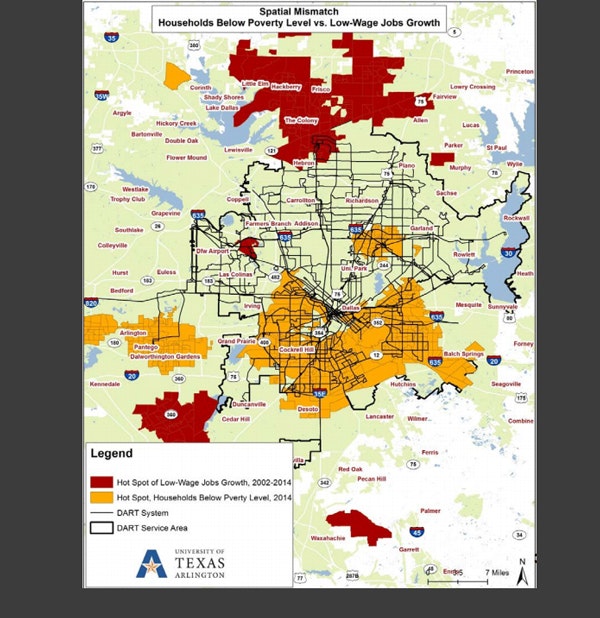

This map from UT Arlington shows that low-wage job growth is greatest in the northern parts of Dallas County, but households below the poverty level are greatest in southern Dallas.

This map from UT Arlington shows that low-wage job growth is greatest in the northern parts of Dallas County, but households below the poverty level are greatest in southern Dallas.

One clear reason some struggle to get a decent-paying job is they often rely on transportation systems that do not connect enough workers to jobs in a reasonable time period.

I grew up in a southern Dallas neighborhood where it can take up to two hours to get to a job located only seven miles away. The neighborhood is within the city limits, but 92 percent of its residents have access to less than 1 percent of the city’s jobs.

The geographic concentration of poverty involves mostly minority families, and southern Dallas residents are most likely to rely on transit because owning a car is too expensive. AAA reports the average cost of owning a vehicle driven 15,000 miles a year costs $706 a month in 2017. When a family earns $30,000, the median household income for southern Dallas, spending $700 to own a car isn’t viable.

The long commutes are also a result of the once-intentional economic disenfranchisement of neighborhoods by the demolition of poor, usually black and brown, communities. These places were leveled to make highways and roadways that effectively cut access to jobs. Many exclusionary policies were implemented without much thought to the impact they would have on the residents themselves.

The long commutes are also a result of the once-intentional economic disenfranchisement of neighborhoods by the demolition of poor, usually black and brown, communities.

One example is the construction of a freeway in the 1950s that cut directly through the heart of the burgeoning freedman’s Tenth Street neighborhood in Dallas. The highway provided a more fluid movement of goods and people from white suburban neighborhoods to downtown. But it simultaneously demolished African-American businesses, separated neighborhoods, and destroyed homes.

A brand-new portion of Central Expressway near downtown Dallas in 1949. The original neighborhood, now split by highway, is visible in the background. (via Texas State Library and Archives Commission)

A brand-new portion of Central Expressway near downtown Dallas in 1949. The original neighborhood, now split by highway, is visible in the background. (via Texas State Library and Archives Commission)

This history matters because the transportation route was built with little regard for those who were left behind and separated from economic opportunity. These infrastructure designs and policies represented the societal values of the time.

The challenges that some Dallas residents face is not unique to their city. Communities have been torn apart to make room for highways in places like Chicago, Denver, and Detroit. And finding transportation access to good-paying jobs is a reality residents in a number of American cities face.

In Nashville, according to a new Institute for Transportation & Development Policy (ITDP) report, less than 23 percent of jobs in the city are accessible by a 10-minute walk or bike ride to a transit station. The report finds that “service is either too infrequent and/or not close enough to the greatest concentrations of where people live and work.”

If we are truly interested in making upward mobility a reality for all Americans, cities nationwide should pursue a range of improvements to help their most marginalized communities.

If we are truly interested in making upward mobility a reality for all Americans, cities nationwide should pursue a range of improvements to help their most marginalized communities.

Here are several key changes to consider:

Provide more transit options and accessibility for commuters. This priority should include streets and sidewalks that allow for more cycling and walking. Currently, Dallas has 19 miles of buffered bike lanes and 45 miles of shared lanes. The lack of sufficient bike lanes results in too few commuting options. Dallas has approved plans like the Complete Streets Initiative to improve how streets are designed and built, but the implementation is slow.

While Dallas has added dedicated bike lanes, many commuting cyclists are still forced to use shared bike lanes or standard roads. (photo via <a href="http://dallastrinitytrails.blogspot.com/2012/09/deep-ellum-shared-bike-lanes-on-main.html">Dallas Trinity Trails</a>)

While Dallas has added dedicated bike lanes, many commuting cyclists are still forced to use shared bike lanes or standard roads. (photo via <a href="http://dallastrinitytrails.blogspot.com/2012/09/deep-ellum-shared-bike-lanes-on-main.html">Dallas Trinity Trails</a>)

By contrast, the ITDP report notes that places like Denver have set targets for reducing drive-alone trips and increasing different transportation modes. “Denver’s 2020 Sustainability Goals,” the report says, “provide a mobility framework that promotes transport options including public transit, carpooling, biking, and walking to reduce drive-alone travel to no more than 60 percent of all trips by 2020 (down from the current 75 percent).”

Expand bus and rail offerings that are attuned to the needs of the residents the transit system serves most. With a large share of riders living in the southern half of the city, Dallas is not doing a good enough job serving those who most need transportation options. My aunt, who lives 30 minutes from her downtown job, prefers public transit. But she cannot use this more affordable option because the Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) shuttle system that links to the nearest rail station doesn’t begin running until 5:30 a.m. This is a relatively late start and effectively prevents her from getting to work on time.

Create partnerships to address transit gaps. The same ITDP report cites how DART and ride-service providers such as Lyft and Uber offer first- and last-mile solutions. Using an app, riders can reserve Uber or Lyft to begin or complete trips not covered by DART. Lyft is also piloting flat rate $2.50 rides to the grocery store for low-income families living in food deserts in Washington, D.C. Those are innovative market solutions.

Create affordable housing closer to better-paying jobs. In Dallas, the vast majority of new multi-family development in 2017 targeted the upscale market. That may meet the needs of affluent residents, but according to City Hall, Dallas has a shortfall of 20,000 affordable housing units. My hope is that the city’s new comprehensive housing policy sets us on the right path.

Invest in low-income communities so employers will want to create jobs there. There are some models to follow: Dallas’ GrowSouth initiative has jumpstarted revitalization efforts in parts of southern Dallas. Detroit is attempting to rebuild its city through neighborhood-by-neighborhood campaigns led by large corporations such as JPMorgan Chase. The effort is reviving local real estate, launching small businesses, and training citizens for middle-class jobs.

Returning to the tadpole analogy, if we want people to succeed beyond the “rivers” of their birth, we must remove impediments to their progress. Their paths may be littered with the debris of systems that do not serve them well. But innovative solutions that reflect our commitment to compassion and equality will ensure our neighbors have the basic services and opportunities to lift them out of poverty.

The Catalyst believes that ideas matter. We aim to stimulate debate on the most important issues of the day, featuring a range of arguments that are constructive, high-minded, and share our core values of freedom, opportunity, accountability, and compassion. To that end, we seek out ideas that may challenge us, and the authors’ views presented here are their own; The Catalyst does not endorse any particular policy, politician, or party.

-

Previous Article The Fight Against Breast Cancer Illustrates the Health Care Challenges of Women in Poverty An Essay by Dr. Quyen Chu, Presidential Leadership Scholar and Chief of Surgical Oncology at Feist-Weiller Cancer Center at Ochsner-LSU-Health Sciences Center in Shreveport, Louisiana

-

Next Article Engaging Individuals and Changing Systems A Collection of Essays by Policy Experts and Community Leaders