Hacking, Privacy, and Democratic Freedoms in the Information Age

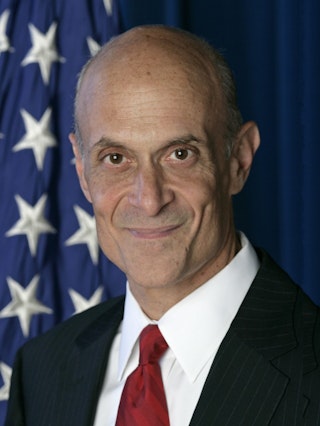

Michael Chertoff served as secretary of homeland security from 2005 to 2009. During that period, the former federal judge faced the real yet perplexing challenge of protecting Americans from further terrorist attacks and upholding civil liberties. As technology evolves and the world changes, how must the U.S. adapt to protect its freedoms but remain safe?

Secretary Michael Chertoff on stage at the Bush Institute's Forum on Leadership in April 2019, alongside moderator and Bush Institute Director of Evaluation and Research Eva Chiang and Unisys CEO Peter Altabef. (Grant Miller / George W. Bush Presidential Center)

Secretary Michael Chertoff on stage at the Bush Institute's Forum on Leadership in April 2019, alongside moderator and Bush Institute Director of Evaluation and Research Eva Chiang and Unisys CEO Peter Altabef. (Grant Miller / George W. Bush Presidential Center)

While at the Forum on Leadership at the Bush Institute, Michael Chertoff sat down for a Catalyst conversation with Lindsay Lloyd, the Bradford M. Freeman Director of Human Freedom at the Bush Institute, and William McKenzie, editor of The Catalyst. Chertoff shares his views on the cyber challenges China and Russia present and how the United States can best respond to them, including protecting our voting systems. The chair of Freedom House also explains the tension between autonomy and privacy in our internet age and how the battle over data reflects the tension between liberal democracies and autocratic nations.

What type of cyberattacks should we worry about most?

It has changed over time. When we first started to worry about cyber security issues, we were worried about criminals who were going to use cyber means to steal our identities, transfer money, or otherwise commit fraud. That is still a big issue and has become quite significant.

But the two areas now of greater concern are attacks that would disable or destroy critical infrastructure. We’ve seen that with the ransomware attacks on Ukraine and at least some probing of our electric utilities and other critical infrastructure, including by the Russians.

There also is a concern about the use of social media for what the Russians call “disinformation operations.” Those are efforts to destabilize democracy by trying to affect elections, create social disorder, and even promote violence.

You mentioned Russia, and all eyes have been on them with good reason. But what about China? Is it equally likely to become a threat?

The Chinese have used cyber means to steal intellectual property or sensitive technology. I don’t think they’ve been quite as active in disinformation operations but they have been doing some. For example, when there’s a negative online story about China or the Chinese Communist Party, they will sometimes suppress it in search engines. They will use artificial means to manipulate.

Of course, more generally, the Chinese have used their economic power, their ability to finance projects in other countries, and even their critical technology as a way of promoting their agenda globally. And, as Freedom House noted in its Freedom on the Net report late last year, when the Chinese embed internet-related technology in countries in Asia and Africa, they will often teach the governments how to use it as a tool of social control. They actually bring people back to Beijing to learn how to use this technology to monitor and observe your population.

Strategically, China is using cyber tools as part of a larger effort to become the dominant factor in the global economy and global geopolitics.

Strategically, China is using cyber tools as part of a larger effort to become the dominant factor in the global economy and global geopolitics.

What do we do?

First, we need a strategic all-tools approach to China. It’s not just about positioning ourselves militarily to not be defeated or handicapped by China. It is recognizing that we have to be playing ecologically and technologically on the global arena, including our democratic values, if we are to be an attractive alternative to China.

For example, we have to help countries in Asia and Africa with investments in health and economics, just as we did with the PEPFAR initiative. We’ve got to use our ability to invest and aid countries as a way of presenting an alternative vision for them about how to develop. That includes financing projects in a way that doesn’t put them at the mercy of predatory loan terms like the Chinese use to come in and take ownership.

It’s not just about positioning ourselves militarily to not be defeated or handicapped by China. It is recognizing that we have to be playing ecologically and technologically on the global arena, including our democratic values, if we are to be an attractive alternative to China.

We also need a serious look at whether Chinese technology is going to become the backbone of 5G, which is basically the next generation of the internet. If Chinese technology does become the backbone, China will essentially decide the rules and have the ultimate control over the internet highway of the future. That is one of the reasons, I think, that the U.S. government has been active in counseling our allies not to be looking to Chinese companies to create the 5G backbone.

Back to the Russians. How do we best prepare to deal with them on cyber issues?

First, we need to continue to collect and publish information about what the Russians are doing. Second, we need to continue to work with critical infrastructure to raise our defenses in terms of direct cyberattacks. Third, we need nonintrusive ways to defend against information operations.

This last one is tricky because we do believe in free speech. But the social media platforms need to be, as they’re beginning to be, more engaged and more effective as they’re addressing Russian efforts to impersonate Americans or pretend to be people that they’re not. They need to basically shut those accounts down and combat artificial amplification of certain messages.

The Russians will continue to validate particular kinds of posts or messages that they want to promote. They aggravate one side or the other of the political debate. These are generally well-written, respected posts. They are designed to create the illusion that the crowd is approving it.

Social media platforms need to be able to use their artificial intelligence to identify what are not natural, organic tweets or likes and shut those down so that their engines for determining what’s popular and what’s not popular can’t be manipulated.

Social media platforms need to be able to use their artificial intelligence to identify what are not natural, organic tweets or likes and shut those down so that their engines for determining what’s popular and what’s not popular can’t be manipulated.

Let me read you a quote from Robert Kagan of the Brookings Institution. He recently wrote: “The world is divided into two sectors. One in which social media and data are controlled by the government, and one in which individuals still have some protection against government abuse.” To what extent is this battle over data playing into the tension between democracies and autocratic nations?

There is no question that there’s a fundamental difference in the view of the internet and social media and any ability of people to communicate online. If you go to the western world and talk about cyber security, people generally are referring to protecting the security, confidentiality, and integrity of the internet to people. When you go to Russia and ask them about cyber security, they’re talking about controlling information and making sure that people don’t see the information they don’t want them to see.

You have the Great Firewall of China and the Russians are now talking about the ability to disconnect from the internet. They don’t want messages that they see as politically problematic being circulated to their people. That is a fundamental divide between western liberal democracies and authoritarian states.

They don’t want messages that they see as politically problematic being circulated to their people. That is a fundamental divide between western liberal democracies and authoritarian states.

That said, even western liberal democracies are struggling with how to address information operations without cutting freedom of speech. We want to have people express messages even if we disagree with them or think that they’re wrong. But we don’t want foreign powers manipulating the mechanics of the internet to create an illusion of trust or bogus popularity.

The challenge that social media companies face is defining their responsibility. What do they have the authority to do? And what does the government have the authority to do? That topic is now very much being discussed.

You have argued for “autonomy not privacy.” What’s the difference? And why do you make that argument?

Privacy typically means confidentiality, the ability to keep things to yourself. If you look at the amount of data we generate now, not just what we put on social media but what other people can put on the internet about us, it is not very realistic anymore that you can keep things confidential or secret. Unless you are really good at staying off the grid, you’re going to generate a lot of data. It all gets aggregated and can be collected.

The challenge becomes not only do people have visibility into everything that you do, but is this actually taking away your freedom? If everything that you eat, when you exercise, where you go, what you read, and who you talk to is now being monitored by people and can be seen by your employer, insurance company, or anyone else, are you going to start to wonder how every decision you make is going to look? Is this going to hurt me with my employer? Is this going to hurt me with my insurance company?

At that point, you’re not free anymore. At that point, you’ve got Big Brother not sitting in your apartment, but sitting in your phone and walking with you everywhere you go. The issue of who controls the data about you becomes an issue of freedom more than just a question of confidentiality.

At that point, you’re not free anymore. At that point, you’ve got Big Brother not sitting in your apartment, but sitting in your phone and walking with you everywhere you go.

How is autonomy different?

Autonomy is about freedom. Even if you can’t stop all the information about yourself from being generated, you can still be given the right to control the information. Before somebody uses or sells it, they should be telling you what they have and asking for your permission to use it.

Protecting autonomy is about giving you the right to have visibility to what data is being held and who holds it, giving you the right to affirmatively consent to any use of the data you didn’t originally agree to, and then making sure you have a real choice when people ask to use your data in a certain way. A monopoly can’t say, “You have to give us your data or you can’t use our service.” They have to offer you an alternative that doesn’t involve surrendering control of your data.

Smart speakers in every room of the house add convenience — but could carry privacy risks.

Smart speakers in every room of the house add convenience — but could carry privacy risks.

Even if you can’t stop all the information about yourself from being generated, you can still be given the right to control the information. Before somebody uses or sells it, they should be telling you what they have and asking for your permission to use it.

You also said that you think the government is much more adaptable on these issues than the private sector. How so?

Ironically, because people usually worry about the government, the government is more prone to be careful and protect privacy. We have built an institutional structure around the government in which privacy has been designed from the get-go.

We have rules about what can be connected, what has to be minimized, and what the predicates are for seeing or using our data. Then there are legal remedies when these things are misused.

I’m not going to tell you it’s perfect. But, from my experience working in the government, the vast majority of people understand that if they misuse the data that has been collected, then they’re going to get punished. Very embedded in the culture is that you follow the rules every time you want to use the data. Periodically, there’s a controversy about a particular use. It gets resolved with a legal outcome and then that gets embedded in the law.

For a long time, we’ve not done that with the private sector. The result was that it had pretty much unfiltered ability to use the data as long as you signed up for a lengthy terms of service. And that wasn’t much of a choice if you wanted to use the service.

What should we be doing about the security of our voting systems?

A number of things. One is the infrastructure obviously needs securing. Voting machines are pretty secure because they’re largely not connected to the internet, except very, very briefly when the data is being exported. Clearly, you want a paper record of all the votes so you can go back and verify them.

How you tabulate the votes and report them have to be secure as well. Even the way the media transmits this information needs to be secure. A couple years ago during an election in Ukraine, the Russians hacked into a TV station and attempted to alter the result that was being reported. They understood there was going to be a real tally, but they thought that it would cause doubt if people got conflicting sets of results.

It’s not that the Russians believe that they can actually flip the result of an election. But they can undermine public confidence and legitimacy.

How does the United States best present an alternative vision? How do we go to a country that’s in transition, or wants to transition, and help them take the democratic path rather than the Chinese or Russian model?

We’re a little challenged here, but it’s to lead by example. The Chinese argue they produce results, which may be their strongest argument. They say they are innovating because they have systemic success.

If you talk to the Chinese, they will say they don’t have free elections but they have legitimacy through results. If the leader doesn’t produce results, then he or she will be out at the next party congress.

So, part of what we need to do is to start producing results. We need our government officials to spend less time worrying about how things are going to look on TV ads and similar marketing efforts, and more on what the actual results are that we want to produce. There are things that we want to agree on that would actually accomplish things and that would be helpful.

That said, I still think our rule of law is strong, our freedom of speech is strong, and we need to get out there using foreign aid, U.S. investment overseas, and bringing students from other countries into the U.S. to let them see up close how our country operates. Frankly, we need exchange programs with our allies’ militaries where we bring them in and they work with us here.

All of these things model the values of our system in a way that are very powerful exports.

The Catalyst believes that ideas matter. We aim to stimulate debate on the most important issues of the day, featuring a range of arguments that are constructive, high-minded, and share our core values of freedom, opportunity, accountability, and compassion. To that end, we seek out ideas that may challenge us, and the authors’ views presented here are their own; The Catalyst does not endorse any particular policy, politician, or party.

-

Previous Article Henry Kissinger on Artificial Intelligence, Authoritarianism, and Hope A Conversation with Henry Kissinger, Former Secretary of State

-

Next Article America’s Values Will Help Win a New Cold War A Conversation with Niall Ferguson, Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University and at the Center for European Studies at Harvard University