When help holds families back

Despite decades of growth, many Americans still feel left behind. To change that, we must fix our social safety net so it promotes advancement instead of trapping families in hardship.

American home with a U.S. flag. (Maxy M via Shutterstock)

American home with a U.S. flag. (Maxy M via Shutterstock)

One of the central contradictions in American politics today is that, despite decades of measurable progress for low-income families – marked by declining poverty rates, rising household incomes, and greater levels of consumption – many families continue to feel as though they are falling behind. Child poverty rates have dropped to near historic lows, and when government benefits are included, the incomes of the most vulnerable Americans have risen steadily in recent years, even adjusted for inflation. Yet the dominant perception remains that American families are barely getting by. These perceptions have intensified political pressure to further expand government assistance.

Why do these inaccurate perceptions persist? While many factors are at play, I want to focus on the structural flaws embedded in safety net programs. These programs successfully redistribute income to low- and even middle-income families and alleviate short-term material hardship. But the way they are designed often undermines long-term advancement by discouraging work and marriage, the key drivers of upward mobility. In other words, current U.S. programs can leave American families feeling trapped – risking abrupt reductions in their benefits if they work more hours or earn higher wages, and facing financial penalties if they marry, since they could then lose their eligibility.

The system clearly needs to be reconfigured. Yet the progressive and populist forces so powerful in U.S. politics today want to expand government benefits without fundamental reforms. Doing so would only worsen the current dynamics, however, by further undermining employment and marriage, jeopardizing long-term prosperity in the process. A far better solution would be to fix the flaws in the current safety net programs – and better align government assistance with the goals of independence and opportunity.

The policy challenge

Over the decades, U.S. social safety net programs have transferred massive amounts of benefits to Americans with limited resources. According to the Congressional Budget Office, before the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020, nearly 70% of U.S. households in the lowest income quintile – that is, households with the lowest 20% of income – were receiving a means-tested government benefit, including Medicaid and other public health insurance. (During the pandemic, nearly all U.S. households in the lowest quintile received some government aid.)

These numbers help explain why, in 2019, the average pretax and prebenefit income for U.S. households in the lowest quintile was $25,200 (in 2021 dollars) – but rose to $41,600 when one factored in after-tax benefits and other government transfers. In other words, even before the massive benefit expansions that occurred during the pandemic, the U.S. social safety net provided an average of more than $16,000 in aid to the bottom 20% of American households, boosting their financial resources by 65%.

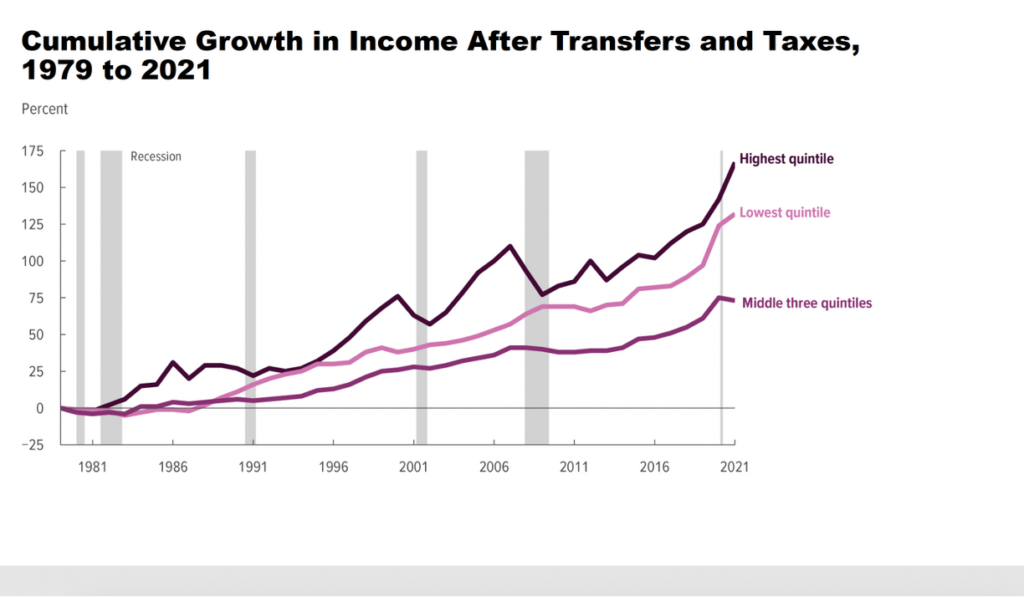

Cumulative growth in average household income after taxes and transfers for those in the lowest quintile has also been impressive over time (see Figure 1). In 2021, real average household income (meaning income adjusted for inflation) after taxes and transfers was 126% higher for this group than it had been in 1979. Even in 2019, before the pandemic hit, real household incomes for those in the bottom quintile were nearly 100% higher than they had been in 1979.

Source: Distribution of Household Income 1973-2021, Congressional Budget Office. Reflects growth in real income.

A sign in a store in New York announces that it accepts SNAP benefits. (Rblfmr via Shutterstock)

A sign in a store in New York announces that it accepts SNAP benefits. (Rblfmr via Shutterstock)

These income trends have translated into progress in reducing poverty. Using one well respected measurement of poverty, 17.7% of American children were poor in 2000. By 2024, that figure had fallen to only 9.8% – an impressive 44.6% reduction.

Despite these economic gains, however, a 2024 Pew Research survey found that 47% of adults in low-income households still viewed the American dream as out of reach. The explanation for this perception is not entirely clear and probably has many sources. What is clear is that many low-income Americans feel that opportunity lies beyond their grasp.

One potential reason is that these people see other segments of the population advancing faster than they are. While absolute measures of economic well-being have improved for low-income households in recent years, their relative position compared with higher-income households has not. Indeed, as Figure 1 shows, the income gains enjoyed by households in the bottom quintile have lagged behind those at the top. Furthermore, while cumulative growth in household income after taxes and transfers for those at the bottom has outpaced those in the middle, much of that progress has depended on government transfers rather than market income – that is, income from earnings and investments. Many low-income families remain reliant on public support, even when they work, which may help explain why they feel as though they are falling behind. Inflation, meanwhile, has only added to these pressures.

Unfortunately, structural flaws in the design of our safety net programs tend to increase low-income Americans’ dependence on government support – and likely their frustration as well. Despite unprecedented levels of federal and state spending, many current safety-net programs actively discourage work and penalize marriage – two pathways most associated with higher household incomes, whether through increased individual earnings or dual-earner arrangements.

Policies that distort

Social safety net policies can influence a range of personal decisions, including not just employment and marriage but also choices about fertility, education, savings, health, and where to live. Badly designed government programs can negatively impact all of these decisions, making it more difficult for lower income households to increase their incomes and achieve self-reliance.

Economic theory and empirical evidence both show that the availability of government assistance makes employment less critical; such assistance can affect individual decisions about how much to work and whether to work at all. The generosity of benefits and the rules governing how they phase out as income rises can also affect both decisions. When safety-net benefits are not conditioned on employment, individuals sometimes choose not to work, jeopardizing their long-term economic progress. A second problem arises when benefit rules are structured so that if a household increases its earnings, it may face an abrupt reduction in benefits – a situation often called a “benefit cliff.” In the most extreme cases, an individual could even lose more in benefits than they gain in earnings. Such arrangements lead many low-income households to rationally choose to work fewer hours or turn down pay raises.

A similar dynamic exists with marriage. Marriage tends to increase household income, since, in many families, both spouses work. Because means-tested benefits are typically calculated at the household level, however, two adults who marry may see their combined household income push them above eligibility thresholds – which means they lose their benefits. Such rules effectively penalize those who chose to get married, and in some ways encourage unmarried cohabitation – even though marriage is one of the strongest predictors of long-term economic stability and child well-being. Although the precise effect of safety net programs on marriage rates remains poorly understood, research by the Sutherland Institute in Utah suggests that program rules that penalize marriage do negatively affect participants’ decisions about whether to wed.

The cash conundrum

A natural reaction to the perception that families are struggling is to increase public support. Populist policymakers have responded with proposals such as universal child allowances, guaranteed basic incomes, universal childcare, and rent controls, reflecting the belief that more government support is always the answer to economic insecurity. In reality, however, such measures risk deepening dependency and diminishing hope for upward mobility.

This truth was highlighted by two recent studies of different unconditional cash payment programs in the United States. Both studies used a random assignment research design – the gold standard in research methods – to measure the effects of unconditional cash handouts on various outcomes. Both studies suggest that unconditional payments may reduce employment without achieving many positive results. The first study randomly assigned 1,000 adults to a treatment group that received $1,000 per month for three years and compared their outcomes to a control group that received $50 per month during the same time. The results, compiled by a team of researchers, showed that the employment rate – that is, whether one worked or not – among participants who received the larger payment was 3.9 percentage points lower than it was among the group that received the low payment. Among participants who worked, those in the high payment group also worked fewer hours than those in the low payment group. And the entire high payment group increased the time members spent on leisure activities compared with those in the low payment group. As a consequence, when not counting the cash payment, the high payment group had lower overall income than the low payment group.

The second study, called Baby’s First Years, also randomly assigned participants to study the effects of unconditional payments, though this time the focus was on the early years after a birth. Four hundred new low-income mothers were placed in a high payment group that received $333 each month over four years, while 600 low-income mothers were put in a control group that received $20 per month over the same time period. Researchers looked at a variety of outcomes, including effects on maternal employment, and the results showed that the higher payments did not improve most child outcomes and had no effects on subsequent fertility.

Interpreting the effects of the program on maternal employment requires careful consideration, especially since the results have been largely misconstrued in the popular press. While it is true that from a statistical standpoint, low-income mothers who received the higher payments worked about the same amount as those who received lower payments, the small number of mothers included in the study made it difficult for researchers to detect anything but very large effects on employment. In fact, the results showed that the higher payments had consistently negative effects on employment, but because of the small number of mothers receiving the higher payments, the researchers could not rule out that those differences were caused by chance. Despite the small number of mothers in the high payment group, researchers were able to conclude with confidence that in the second year of the program (which corresponded to the COVID-19 pandemic), mothers in the high payment group worked substantially fewer hours than mothers in the low payment group. Taken together, the results from these studies are consistent with economic theory, which holds that that unconditional payments lead to fewer people working and to people working fewer hours.

Flyers on a table during a job fair in Buffalo, New York on Aug. 27, 2025. (Lauren Petracca/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Flyers on a table during a job fair in Buffalo, New York on Aug. 27, 2025. (Lauren Petracca/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

These findings should cast serious doubt on proposals for guaranteed income programs or universal child allowances. They also highlight the risks of yielding to populist pressures for ever-expanding government assistance, particularly given the work and marriage disincentives embedded in current safety net programs. A more constructive path lies in reforming the safety net to better encourage employment and marriage. This would mean constraining and redesigning programs to promote self-reliance while avoiding policies that deepen long-term dependence on government aid.

Incentives for success

Overall, the main objective should be to redesign the government-aid system to provide short-term financial assistance to low-income families while supporting their long-term success by encouraging (or at the very least not discouraging) employment and marriage. Policymakers should consider five key reforms as they seek to do so.

- Work requirements in safety net programs are often mischaracterized, due to confusion about who is actually affected and the specific obligations involved. Essentially, work requirements place reasonable conditions on adults capable of working (that is, people who are not disabled or otherwise unable to work); to keep getting assistance, they must either maintain employment or participate in work-related activities such as training, job preparation, or community service (typically on a part-time basis). Work requirements were pivotal in increasing employment and decreasing dependence on assistance among single mothers after the 1996 welfare reform law. Similarly, unemployment insurance has long required that beneficiaries must show they are searching for work in order to remain eligible for compensation. Earlier this year, Congress expanded work requirements in the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” to a larger share of work-capable recipients of food assistance and for the first time placed a similar requirement on work-capable Medicaid recipients. Even after these changes, however, work requirements for most safety net programs remain relatively modest. To maintain eligibility under the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), only those adults under the age of 65 who are not disabled, are healthy enough to work, and are not caring for a child under age 14 need to work or participate in a qualifying activity on a part-time basis. Medicaid also requires part-time employment or volunteer activity for nondisabled, healthy adults without children under 14, but verification is only required at the time of application and recertification, meaning in one out of every six months.

- Congress should impose an employment requirement for work-capable adults across all federal safety net programs. Similar requirements should be inserted into housing assistance programs, and Congress should expand requirements to a larger share of work-capable benefit recipients in SNAP – for example, by excluding only those parents with caretaking responsibilities for children under 6. Not only will these efforts encourage employment, they will also constrain federal costs by targeting benefits to the most vulnerable populations.

- Reduce benefit cliffs. A crucial design flaw in current safety net programs is the way those benefits phase out and eventually terminate. By definition, all means-tested benefits (as opposed to universal benefits) must shrink as income rises, so all workers enrolled in such programs will eventually lose some portion of their benefits as their earnings grow. Programs should phase out benefits at a predictable and reasonable rate, however, so that the loss in benefits is manageable and the impact it makes on decisions about employment is minimal. For example, if an individual loses $25 in benefits for every $100 in additional earnings, that individual will retain an incentive to earn more; they’ll still net $75. This calculus changes, however, if the loss in benefits erodes a more substantial portion of additional earnings. The result of such an arrangement is often that individuals are deterred from taking on additional work or accepting higher pay. This is particularly the case when benefit losses completely offset additional earnings, meaning the individual’s net income does not rise even if they work and earn more.

- Under current rules – particularly in cases where households participate in multiple programs – benefits often remain relatively high as families approach the income eligibility limit, rather than gradually phasing out. This abrupt cutoff creates a sudden loss of assistance that, research has shown, can be substantial enough to influence employment decisions. A common proposal for dealing with this problem is to expand eligibility further up the income scale so that benefits can phase out more gradually. Such an approach is fiscally unsustainable and counterproductive, however, as it would be tremendously expensive and would draw additional households into government programs and extend the very work disincentives these reforms seek to reduce.

- Instead, Congress and state governments should focus on realigning benefit rules within individual programs and coordinating reforms across programs so that assistance phases out at a more predictable and reasonable rate. Achieving this goal without expanding program costs will likely require lowering benefit levels while extending more gradual phase-outs.

- Require more state funding, but give states more flexibility. Another solution involves requiring states to fund a larger share of benefits, while also giving them more flexibility to reform program rules. Currently, state governments have little incentive to reform major safety net programs because the federal government funds benefits almost in their entirety. Requiring states to contribute a larger share of funding will increase their incentives to encourage employment as an alternative to receiving benefits, to address marriage penalties, and to reduce benefit dependence. These efforts will reduce federal costs, by shifting a portion of responsibility onto state governments and incentivizing them to accept fewer recipients.

- Make program eligibility limits more generous for married families. One option for addressing marriage penalties is to expand income eligibility for married families so that when two married parents combine their incomes, they remain eligible for benefits. Currently, the earned income tax credit (EITC) operates this way in part, with married parents remaining eligible at slightly higher income levels compared with unmarried parents. Expanding income eligibility for married families – or combining a reduction for unmarried families with an expansion for married families – would further address marriage penalties in the EITC. Congress could take a similar approach for other programs, such as housing and childcare assistance, either on a permanent basis or at a minimum during the early years of marriage. Expanding income eligibility for married households would raise government costs by increasing benefits to higher-income households, which directly contradicts other proposals to constrain costs and caseloads. Policymakers must balance these additional costs with the desire to address marriage penalties, however, and consider offsetting savings – including reducing benefits for work-capable adults in childless households.

- Expand Supplemental Security Income and Medicaid access to married couples. Congress should also explore ways to reduce marriage penalties in Supplemental Security Income (SSI), a low-income disability and retirement benefits program, and in Medicaid. The reality remains that low-income disabled people risk losing some or all SSI benefits and their health insurance coverage through Medicaid if they decide to marry. Congress has proposed legislation to eliminate the marriage penalty in SSI asset limits, and should build on these efforts to eliminate marriage penalties for all disabled people, identifying suitable offsets to cover the increased benefit costs.

On average, most Americans today are better off economically than at any point in recent history. Yet the common perception remains that families are struggling to make ends meet. Among low-income households in particular, the belief that the American dream is out of reach is especially strong. While the populist desire to expand government assistance may appear to be the answer, fixing structural flaws embedded in safety net programs offers a more sustainable solution by prioritizing the institutions that foster upward mobility: employment and marriage. By reforming safety net programs, policymakers can address the perception of stagnation and build the conditions necessary for upward mobility. Doing so will ensure that opportunity remains accessible, that work is rewarded, and that marriage remains the cornerstone of American family life.

The Catalyst believes that ideas matter. We aim to stimulate debate on the most important issues of the day, featuring a range of arguments that are constructive, high-minded, and share our core values of freedom, opportunity, accountability, and compassion. To that end, we seek out ideas that may challenge us, and the authors’ views presented here are their own; The Catalyst does not endorse any particular policy, politician, or party.